Katsushika Hokusai: Swept away by Japanese genius

Hokusai's Great Wave has influenced Western art and culture for nearly 200 years. Adrian Hamilton takes a look at the British Museum's new purchase

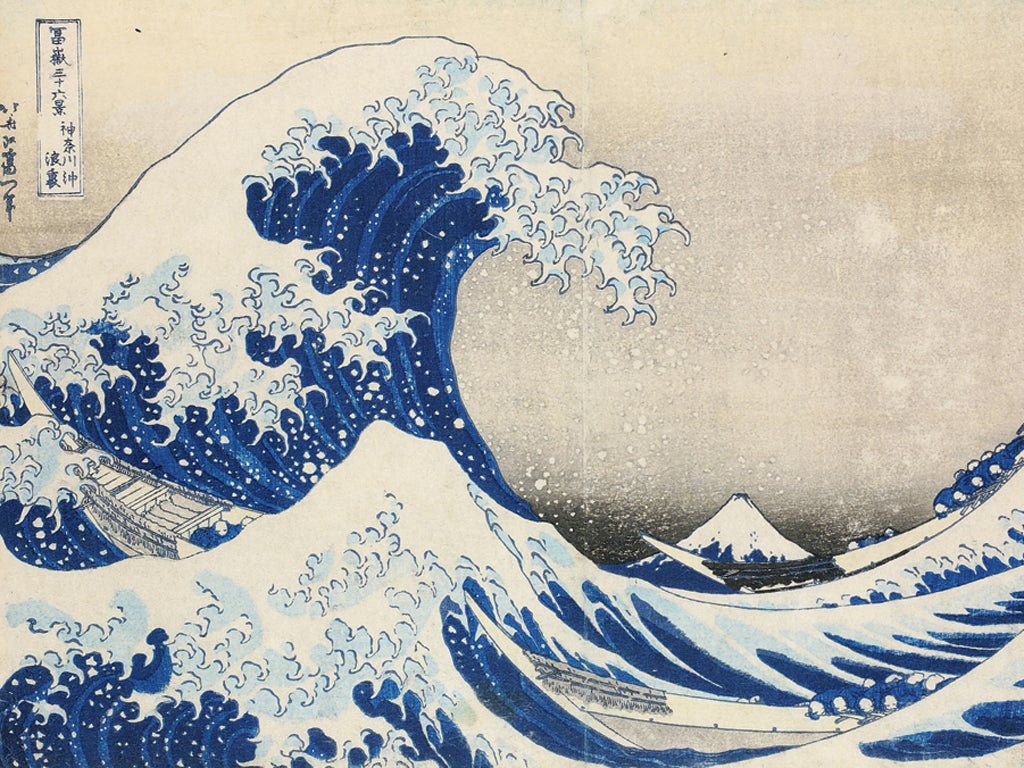

Go up the steps of the main entrance of the British Museum, turn immediately to the right as you pass through the door and there, in a room to itself, is the most iconic, and to my mind one of the greatest, images of all art. Indeed this picture of a giant wave rearing above the skiffs below could be the symbol of our times as the euro crisis, recession and the decline of the West threaten to engulf us all.

It would be no surprise if it did become the emblem of our day. Great Wave by Katsushika Hokusai – or Under the Wave, off Kanagawa as it was properly titled – has been used for everything from the cover of Debussy's score of "La Mer" to Tintin's desperate cry of "Mon vieux Milou, nous sommes perdus" in The Cigars of the Pharaoh. Comics, advertising, Impressionist painting, pop art and music have all been influenced by the discovery in the West of Japanese prints in general and Hokusai's works in particular.

Yet Great Wave, which dates from 1831, is not a unique work in that it was a wood-block print produced in its thousands at the time. It's not even a one-off, being part of a popular series of 36 Views of Mount Fuji (later increased to 46). The range of colours is limited, the chief one actually being a synthetic import from Germany, Prussian Blue. It's not even that large, being the classic 26 x 37cm oban-sized sheet.

But it is awesome in the sheer energy of its curving rhythm, the boldness of its colour, the grasping tentacles of its surf and the sweeping lines of the sea's swell as the fishermen rush to the back of their skiff to raise their bows to meet it. It's a picture of great subtlety and forethought, as you would expect from Hokusai, the most self-consciously searching of all Japanese artists. The centre is, as it should be in the series, the sacred mountain of Mount Fuji, which had become the object of cult worship at the time and was to be taken up as a symbol of the country itself. It stands solid and snow-capped in the deep distance. The three skiffs, used at the time to ferry the catch from the big fishing boats back to the shore, mirror the line of waves in their length and the sides of the mountain in their bows. In this very early run of the print, bought recently by the British Museum, you can see the delicately delineated water drops cascading down from the waves, appearing like snowdrops above the image of the mountain.

The astonishing thing about this work when you look at it closely is that the artist could achieve such effects with the relatively primitive method of woodblock printing. In this case four blocks would have been used, each carved on both sides. The first and main one would be incised from the paper drawing by the artist to delineate the lines, the other seven faces would be used to fill in the colours. It is the medium that determines the emphasis on composition, line and flat surface that make the Japanese prints such a remarkable artistic genre. But it was Hokusai's genius as a graphic artist that makes this picture such a masterpiece.

It's a work that exemplifies the dramatic interchange of artistic ideas between East and West which has always punctuated history. Western goods, and particular books and prints, were not allowed into Japan until the 18th century. When they did come, mostly in the form of engravings, their impact was dramatic. Perspective became the fashion for the young artists as they sought to imitate the works.

Hokusai was of the next generation. An artist with an endlessly inquiring interest in form and observation, he took these new ideas and applied them to the more traditional Japanese style. "The Great Wave" was produced when he was 71, at a time of change in his life after the death of his wife and a series of strokes. In it, as in other prints of the series, he uses deep perspective but also keeps the exaggeration of elements and two-dimensional quality of Asian art in the foreground. The whole series is an exercise in taking a single still object, the mountain, and playing around with various perspectives.

Just as the Japanese (as indeed the Indians and Chinese) were blown away by Western perspective, so these prints had the reverse effect when they started being imported into Europe in the latter half of the 19th century, when Japan was finally forced to open up to Western trade at the end of a ship's gun. They came as cheap albums and paper products, often used as wrapping for other goods. The young radicals of the time – Degas, Manet, Cézanne, Whistler, Toulouse-Lautrec and Van Gogh – seized on them with a passion. Here was an approach that defied all the conventions of traditional Western art in which they were brought up. Compositions were cropped savagely at the margins, the colour ranges were limited and applied in blocks, the line was paramount, the subjects were of ordinary people and their lives. To a generation desperate to break out from the past, here was the way to do it. Without the influence of Japanese prints, Impressionism and Post-Impresssionism might not have been possible, or at least might well have taken a different turn.

Hokusai was quickly recognised as the artist he was, although not for Great Wave, but for his books of brush drawings, The Manga. Great Wave came into its own in the second phase as the Nabis group and the Expressionists began to appreciate the visual sophistication and graphic impact of the landscape prints of Hiroshige and Hokusai. It became the perfect embodiment of the image in commercial art that lay at the foundation of what we now call Modernism, being painted on walls, used in comics and seized on for advertising.

And if the idea of adopting it as the symbol of our times, reflecting an age of natural and man-made disaster, seems too dispiriting, look at it carefully. The wave may seem all engulfing, but in the still beauty of the mountain and the urgent actions of the sailors there is the sense that we will come out of it at the end.

Hokusai's 'Great Wave', British Museum, London WC1 (020 7323 8299) to 8 January

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies