The Independent's journalism is supported by our readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commission.

Of course Bob Dylan ignored the Nobel Prize, he’s the the antithesis of a pop icon

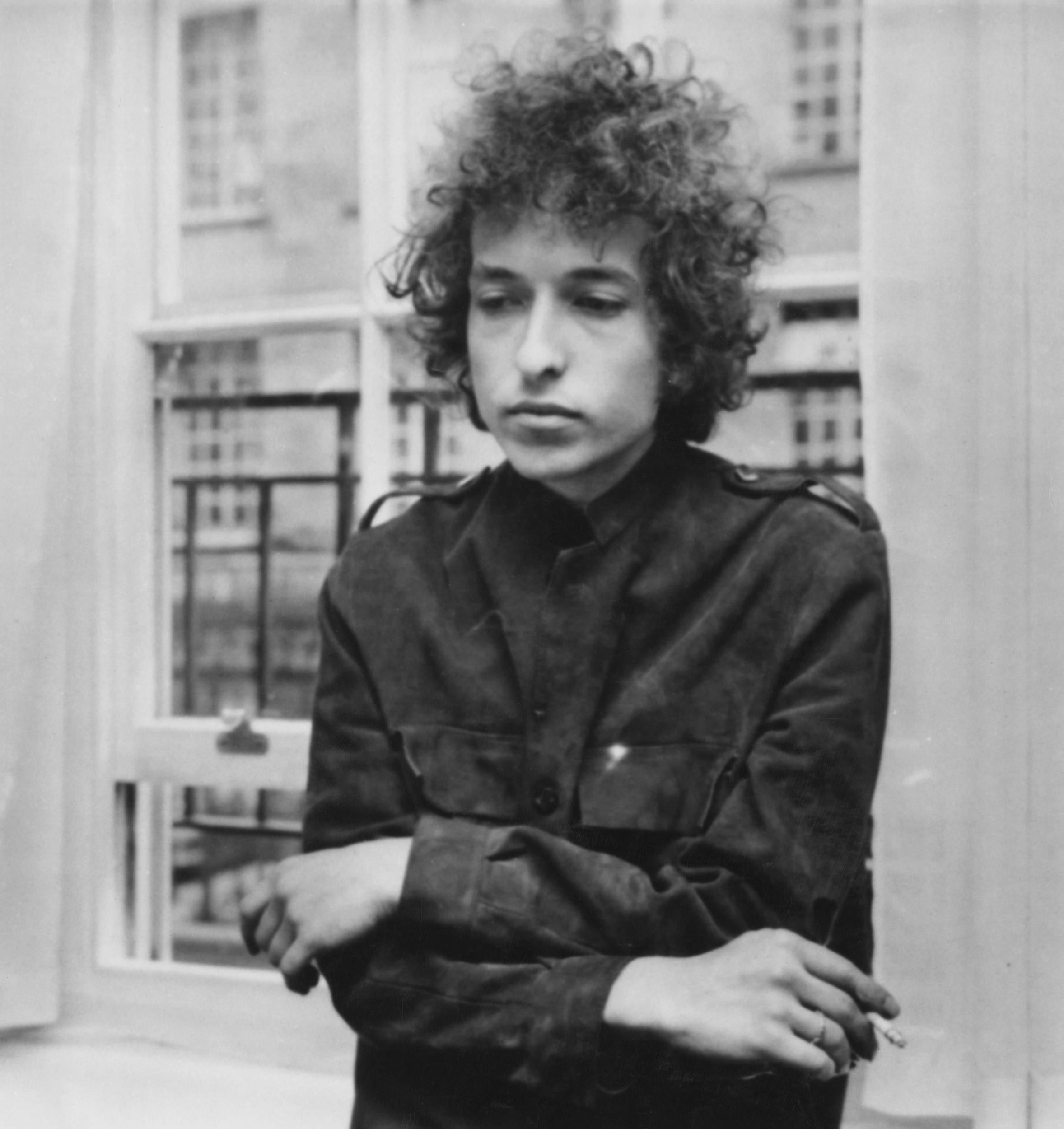

Bob Dylan is being taken to task for his silence after he was announced the winner of the Nobel Prize for Literature, but as Alan Franks writes, the impact of his work cannot be denied – and his aplomb here is just part of the package

It had to happen. Someone in the Swedish Academy just had to pull Bob Dylan up on his manners.

It has taken the whole ridiculous thing even further back into the 1960s. Yes, of course that was the Decade of Youthful Rebellion, but then there had to be something to rebel against. Parental morals for a start. So a huge debt of gratitude is to due to Per Wastberg, the academy member who has come out as a radical throwback by calling the singer impolite and arrogant if he goes on snubbing Stockholm.

It’s already been a week, which may be a long time in politics, but which is an unmeasurably small microsecond in the time it takes boys from that generation to say, let alone, write: “Dear Mr and Mrs Nobel, Thank you so much for the kind invitation to your party. I should be delighted to attend and look forward to it greatly. With best wishes to you and the family, Robert.”

What would his father Abe Zimmerman, a former manager at Standard Oil in Duluth, and his wife Beatty had said if they thought he was leaving socially important invites like this one on the mat? And what might he have replied as he picked up his guitar case and headed for New York? “It’s all right, Ma”?

It has already been a richly entertaining week, full of timeless prejudice and stereotyping. You can warm your face from the angry heat coming off the coverage that has Nobel Eggheads Fuming as Pop Icon Walks off with Book Prize. Which of course is exactly what he hasn’t done; and he is almost the antithesis of a pop icon.

And yet, if he doesn’t turn up in December to receive the prize, he wouldn’t be the first absentee laureate. For a variety of reasons, including health, ideology and political sensitivity, several former winners have stayed away, including Harold Pinter, Doris Lessing and Alexandr Solzhenitsyn. It is not necessarily the snub it is being portrayed as. Besides, the committee accepts it is an award; the winner doesn’t get stripped of it if he or she doesn’t show.

Dylan is only a pop singer if you insist on defining him by his early chart hits of half a century ago. But even then there was something odd about them, and gloriously so. As he himself has said many times and in many ways, he is not mainstream. Although he was always ambitious, and almost as inspired by Elvis Presley as by Woody Guthrie, he has remained peculiarly unassimilated, shifting from style to style, voice to voice, while somehow remaining transparently true to himself.

Film directors have picked up on this perpetual sense of otherness and absence; Sam Peckinpah who cast him as the unknowable Alias in Pat Garrett and Billy The Kid in 1973; director Todd Haines’s 2007 movie I’m Not There, in which Dylan was played by six very different actors.

The more important question has to be whether he is worth the honour. The simplest answer is probably that by being judged worthy of the award by the Swedish Academy, he therefore is. Unless of course you take the view that the Academy is somehow trying to flaunt its broad-mindedness and cultural liberalism. That doesn’t quite work.

If anyone has been breaking the rules, it is Dylan himself, and he has been at it for the past fifty years and more. Having won over the fans of an ailing Woody Guthrie and become a standard bearer for that troubadour of the common man, he then trashes the image by going electric at the famous Newport Folk Festival of 1964.

If, for whatever reason, you can’t remember that affair, it is hard to overstate the perceived treachery of such an action. Vandalism is probably a better word, trampling on so much that the oral tradition held dear and, to his great credit, showing that the American Left could be quite as reactionary as the Right when it chose.

The great thing about Dylan was – still is, clearly – that he really didn’t seem to care too much for repute. Before that dramatic decade was out, he had released, in Blonde on Blonde, an utterly extraordinary double album in which a set of basically rock songs, with pop and country also present, was being asked to bear a weight of literary lyrics such as these genres had never shouldered. Some of them, like I Want You and Just Like A Woman had their moments of edgy directness, but others seemed to be soaring off in search of sublime imagery and knowingly poetic diction.

A few of the visons, of Johanna or otherwise, sounded heroically stoned, and others were just rather beautifully strung, or strung-out words. It didn’t matter exactly what he was trying to say with “the ghosts of electricity howl in the bones of her face.”

You knew, to borrow a slightly later term, where he was coming from.

As for “In the museum infinity goes up on trial,” well, yes, it does, doesn’t it, when you think about it. You’d just never heard such propositions from The Beach Boys, or Buddy Holly, or the Everly Brothers, for all their glories. The thing was, he was saying this stuff, or singing it, and you got the picture. He was going for it, risking at a height, and if he fell out of the sky, so what, you were still interested.

So were the officially clever people from a slightly older generation, and here, probably, are the seeds of the Nobel business. One of these people was, and is the British critic and academic, Christopher Ricks, who brought all his Oxbridge erudition to bear on a question which ran and ran: Who’s better – Dylan or Keats? There isn’t an answer (not for lack of offers), but again this isn’t the point. A popular songwriter – “Like a Rolling Stone” had become a number one hit single – was worthy of mentioning in the same breath as the late great Romantic.

Then there was, to take just one other example, Wilfred Mellers, friend and former pupil of FR Leavis, and professor of music at York University. A poet and musician in his own right, an authority on Couperin, a champion of Mahler, Mellers was able to write a 200-page book, A Darker Shade of Pale: A Backdrop to Bob Dylan, without a trace of condescension or cultural slumming.

The point is surely this. Dylan, like his closest peer Leonard Cohen, got big because he was marrying popular song forms with poetic lyrics. When I interviewed Cohen, he said he was a poet first of all and only got involved with music to the extent he did because it made it easier to make a living. The same may not be so true of Dylan, but they were fusing traditions in a way that hadn’t been done. At least not by English-speaking artists, who lacked the kind of troubadour precedent that could produce a Georges Brassens in France.

In both cases their influences were profoundly bookish, from the European Romantics to their compatriots Walt Whitman and Robert Frost, Ezra Pound and TS Eliot, to say nothing of the Beat authors of their own youth: William Burroughs, Jack Kerouac, Gregory Corso and Allen Ginsberg, the last of whom was one of Dylan’s most significant champions. At the same time he could write stanzas of great simplicity and compression, as he did in the John Wesley Harding album of 1967, or spin a story as full and nuanced as a novella, as in Floater on Love and Theft in 2001.

Something else was happening, as he almost said in one of his songs. Like his contemporaries, he was borrowing from the two vast traditions of British (and Irish) folksong and the Blues roots of his own nation. To some extent he was reworking exiled material and making it American, then international. Borrowing is a sensitive word to use about Dylan, as he acquired a reputation for writing tunes with an astonishing resemblance to earlier ones.

And yet he could not help but give back. Even his most hateful detractors – such as the furious purist Ewan MacColl – could not deny that Dylan’s success was largely responsible for returning listeners to the sources which shaped him. If that irony is a little strong, here’s a gentler one. One of Dylan’s mature revolutions has been the personal one of plundering that other tradition of the Great American Songbook, and coming across a crooner of the very stuff he once seemed to stand against.

Along the way, he has probably done as much as anyone to raise the levels of sheer seriousness that popular music can reach and free it from the dull old snobberies that dismissed it as trivial. Can he be blamed if an exemplary little song, “Make You Feel My Love”, that he dashed off for his 1997 album Love and Theft album got taken up and made into a world hit by Adele?

More than two thousand books have been written about him, and his work features in countless university courses. Who would have thought it? Not me for one; not when I heard a schoolfriend’s father, a veteran headteacher, declare, as if returning sloppy homework: “He looks like a Dickens crossing-sweeper and he sounds like a sheep in pain.” Although, now I think about it, that’s not bad.

What cannot be denied is the spread and depth of his body of work – nearly fifty albums’ worth of original material, varying astonishingly in form and content. Its cumulative presence is like a rough and unruly map of a life – his own for sure but also for those countless unsung ones dipping in and out of an American dream or its waking nightmare, blown almost to oblivion by an Idiot Wind. If there isn’t greatness here, then there may just be none in Updike, Roth, DeLillo and the rest. No, he’s not a novelist, and no-one is suggesting he is one. Particularly if they tried to read his one shot at the form, Tarantula. But then Updike and the rest didn't choose the song form.

Although he went on changing like the times – the habit at least was permanent – that early period, from the early 1960s to the mid-1970s is widely reckoned to be his finest, culminating in the bleak but brilliant Blood on the Tracks in 1975, and the intense reflections of Desire a year later.

Some of the critics who find him a wrong-headed choice for the Nobel argue that he has done little of merit since then. True, there was a loss of writing form in his so-called religious period, when the certainties of faith proved a poor replacement for the conflicts of love, but there have been some magnificent later songs from Time Out of Mind, Love and Theft and Modern Times. It’s a big If, but if these albums had been his first rather than his forty-first, he would still have been hugely influential.

Since the Nobel is a lifetime achievement gong, its laureates should be taken all in all. On that score, the Academy shouldn’t have any second thoughts. Their citation, “for having created new poetic expressions within the great American song tradition” is on the money, even if it only gets two stars for phrasing.

Dylan may once have been dubbed, rather lazily, a protest singer. In the unlikely event of his Nobel silence being some kind of gesture, then Jean-Paul Sartre got there before him. In 1964, even before that Newport festival, the French existentialist declined the Nobel Prize for Literature. He argued that he did not like accepting these public honours as he did not wish to be “institutionalised”. There’s an old hippie for you.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks