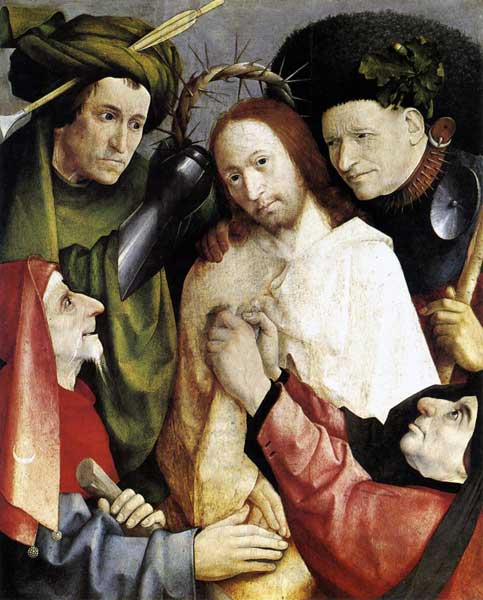

Great Works: Christ Mocked (The Crowning with Thorns) 1490-1500 (73.5 x 59.1cm), Hieronymus Bosch

National Gallery, London

This is an unnerving, uncomfortable painting, and what is more it is rather uncharacteristic of the Hieronymus Bosch with which we are all so familiar. We remember so well, don't we, from the prints of our student days perhaps, all those hellish visionary scenes, set in fantastical landscapes, pullulating with tiny figures, swarming up ladders, upended in barrels, demons and men, in the company of grotesque instruments of torture?

This painting, by contrast, is a relatively small-scale devotional panel, oil on oak, which invites us to meditate upon – and learn from – Christ's suffering in those final hours before his crucifixion. For once, the five figures are writ large, huge in the picture space. There is nothing but these figures, and each face, though inclining towards caricature (yes, is not each one of them more than a little like an animal? Is not the man at bottom left, for example, who stares up with his spiky goatee beard, as goatish as they come?) is very carefully and individually characterised. And then there is that wonderful, throttling, buckled, ruddy collar whose spikes seem to be in earnest conversation with the spikes of the crown of thorns nearby, worn by the malign, narrow-eyed tormentor in the wonderfully flamboyant fur (or astrakhan) hat at top right, a hat which sports an extraordinarily generous sprig of oak, so meticulously rendered that it could be a small and exquisite still life in its own right. This collar looks as if it would be more fitting around the throbbing gullet of Del Boy's mastiff as he walks the sink estate at twilight, panting for his life.

What is more, it feels as if these tormentors have all been pushing their way in, so desperate are they to be included in this scene of ritual humiliation of a terribly meek and compliant man. If the painting had been glazed – which it is not, I must hasten to add – it would surely have been fogged by their hot, rancid breath. In fact, so great is this sense of crowding menace that we almost feel as if we too are being pushed, jostled up towards it, from behind, as witnesses to Christ's torments at the hands of the Roman soldiery. Roman soldiery though?! Surely not. Well, Roman soldiery in sumptuous contemporary dress perhaps. And yet not even that. These men, tricked out in their startlingly colourful clothes – Bosch seldom goes in for such high colours – look more like scheming, prosperous merchants than soldiers. Look again at those two wonderful hats, for example, to left and right at the top of the painting. The hat on the right, with its grandiose sprig of oak – that acorn in its cup winks at us as if it were solid gold – is as affecting as the rings of Saturn. Well, almost. And then there is the equally extravagant hat worn by the man to the left (would soldiers have worn such headgear to be stepping out in?), which is all green folds and pastry-like twists, and is pierced, with an almost brutal degree of efficient brutality, by something that closely resembles an arrow that happens to be just missing the skull. This detail is a delight in itself, demonstrating how the decorative makes playful reference to the martial. Ditto the concave, disc-like, shield-like brooch attached to the coat of the man opposite.

Unnerving, I said. An example of extreme bullying, you might even add. Yes, because it is all so studied, the presentation of the theme of this painting, so full of brute determination. It shows these men getting on with the job in hand, and having nothing else on their minds. They are almost mechanised, these encircling brutes, as if they are not so much men as extensions of the staves that they are wielding with such care and attention. The torture is beginning to happen, this is where we catch the scene, and it is a snatched moment that we are seeing, temporally extremely abridged. This is why the tension is so heightened. The horrible crown of thorns (and can there be a nastier looking crown on thorns than this one? Can thorns and crown ever have looked more menacingly and ruthlessly metallic than this one, ever so long and so sharp?) is being lowered home on to that small head with its brilliant, though slightly lank, auburn hair. We wince even as we look at it. And, to drive the point home, it is being lowered into place, oh quite slowly, we feel – because that is how the best and the most sadistic torturers work, slowly and precisely – with the aid of a massive mailed fist, which gleams so dully black, and also shines reflectively. This fist, such is its shape, scarcely looks human at all. It looks a little as if it might have come out of a painting by Wyndham Lewis of mechanised soldiery.

Yet, most of all, we are here to observe Christ, that meek-eyed man at the centre of this menacing quartet of leerers. They all look at him with a gluey degree of voracious and utterly unloving attention. But Jesus, unlike all the rest, appeals beyond the painting. He looks out, head lolling, sporting a rather wispy 'tache and unmanly ginger beard, beyond the picture frame, and directly into our eyes. He engages us. He invites us to be at one with him at this moment. His skin is so strikingly, strangely pallid, we notice, as is the garment that he is wearing. Yes, he is pale, resigned, and utterly unresisting. He has turned the other cheek. Meanwhile, there are hands everywhere, so many of them, in this painting. We could think of it as a swarm of hands, nine of them in all, touching his knee, bearing down upon his shoulder, and a full two rending his garment. Such nasty, enveloping hands.

ABOUT THE ARTIST

The Netherlandish painter Hieronymus Bosch (1450-1516) was born in Hertogenbosch. Although a deeply religious man, many have regarded him as a heretic for his often wild and fantastical visions and free use of religious symbolism. Closer to our own day, he was championed by the Surrealists as a forefather – a man who could make free and unbridled use of his own dream visions. Bosch, a highly respected member of a religious community, would probably have been shocked and dismayed to find himself in such company.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies