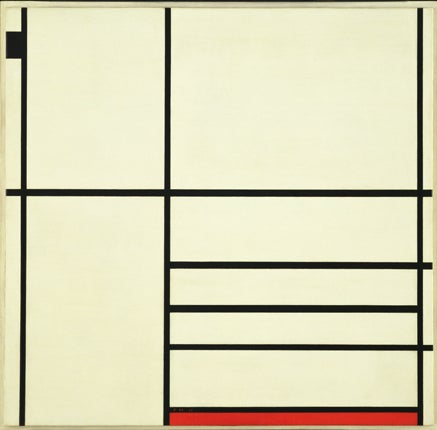

Great Works: Composition in White, Black and Red (1936) Piet Mondrian

People have tried to get computers to compose music, and with some success, especially if the music's form is relatively formulaic. You can program music "in the style of Mozart". It won't be much good, but it can yield something plausible, something Mozart might just have done on an off-day.

Mozart did something similar himself. He played a composition game where you write short bits of music and assemble them according to rules and throws of a dice. It's not a computer, but it's certainly a kind of program.

How about painting, though? Could you do anything equivalent with a picture? Could any program generate, say, a plausible Vermeer or Van Gogh? It's hard to see how. Painting doesn't have bits. Where would you begin?

But there is one artist whose works looks as if they could be programmed. You might not be able to produce a good one. You could surely produce a plausible one. It's Piet Mondrian, of course.

Obviously, we must ignore the actual paint of his paintings. But if you restrict yourself to his abstract designs, Mondrian seems to be an artist with a strict repertoire: clear elements, bits, and clear rules for deploying them. Put this repertoire into a programme, introduce chance variations, and you could make a Mondrian of your own. Many Mondrians of your own.

Concentrate on his classic period, the work around 1930. His elements are lines and coloured panes. The lines are black, straight, fairly thin. The colours are red, yellow, blue, grey or black – and always white. The lines go vertical or horizontal. A single vertical line and a single horizontal line run right across the canvas, edge to edge, intersecting somewhere.

The other lines either cross one another, or meet at T-junctions. There are no naked L-corners. The oblong panes between the lines are filled with colours and whites. Each one is completely and uniformly filled with a single colour (the same colour may fill adjacent panes). Colours can only occur bounded by the black lines or by the picture's edge.

That seems to cover Mondrian's elements and his rules. Maybe there are more than at first sight you'd suppose. But still they're not enough. You could follow these procedures and produce something that looked very little like his work. There are other considerations to be observed.

Each picture has one dominant oblong area, noticeably bigger than the others. The two right-across lines must not intersect too near to the picture's centre. The black lines can vary somewhat in width. These are crucial considerations. But they're not strict rules. How much bigger? How far? How wide? Where to stop? You can't define it.

That's the problem with making a Mondrian 1930 Program. There are probably many things that Mondrian would never have done, but you can't know precisely what. And if you can't be sure of that, you seem to be stuck. The only things you can be sure Mondrian would have done are the things that he actually did.

So much for making more Mondrians? But then Mondrian himself was always trying to make more Mondrians. And he didn't know either, precisely, where to stop. There were things he would never have done – until he did them.

He never had more than one vertical and one horizontal going across the canvas. But then, in the mid-thirties, it happened. These lines doubled, tripled, multiplied, as in Composition in White, Black and Red, the painting here. There are three verticals transversing the picture.

This picture breaks another rule, previously unmentioned. It uses lines that are parallel, of them same length and aligned: two pairs of them occur in the bottom right corner. With all these pronounced parallels, a new range of feeling enters Mondrian's art. The picture is not a structure but a network. It gets airiness, openness. A wind blows through it.

In other pictures of this time other rules get broken. There are red lines, yellow lines. You find bare areas of colour, unbounded by lines. And what you realise is that Mondrian is not performing variations on a set of elements and rules. He's painting individual paintings, one by one, and ad hoc.

His art looks programmatic. Each picture can be broken down into clear and distinct bits – there's absolutely no blurriness – which are to an extent repeated from picture to picture. And there really are a few hard rules, some things that Mondrian will not do (or never did, at least). Every edge is straight. There are no diagonals. There are no naked corners. Colours are always uniform. You'll never find a green.

But beyond that, the problem with trying to make a new plausible Mondrian is not that rules and uncertainties will pile up into paralysis, and all you can do is copy existing Mondrians. The problem is you have too much freedom. You have as much freedom as Mondrian had himself. You can do things he never did, but just might have done. The only way to imitate art is with more art.

About the artist

Piet Mondrian (1872-1944) was the greatest master of modern abstraction. Living in dedicated solitude, and following the principle of theosophy, this Dutchman began painting landscape, but came to reject nature, and reduced his art to a rectilinear grid of black on white, plus the primary colours.

He was the leading figure of the movement called De Stijl, The Style, and practised it with the strictest discipline: he firmly rejected his colleague Theo Van Doesburg for succumbing to the diagonal. But the austerity of Mondrian's art can be exaggerated. It's astonishing what feelings can be wrung from his formations of lines and colours. Once tuned into, it offers one of the most various and expressive forms of modern paintings.

These are precariously calculated compositions, that, as the critic David Sylvester wrote, can "move with the force of a thunderclap or the delicacy of a cat". In his writings, Mondrian took his idea of "dynamic equilibrium" beyond the field of painting, into architecture, urban living, even into international relations, and – before nuclear weapons – he had envisaged the concept of Mutually Assured Destruction.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks