Great Works: Landscape (The Hare) (1927), Joan Miró

Solomon R Guggenheim Museum, New York

We are in the full growth of summer. In the lab, a synthetic cell has just been created. Life burgeons. The myriad organisms have another sibling. And is it a new friend?

Twenty-five years ago, the biologist Edward Wilson announced the term "biophilia, which I will be so bold as to define as the innate tendency to focus on life and lifelike processes." We are drawn, he says, to our fellow creatures, animal and vegetable, great and small. "We are literally kin to other organisms." And he means all them, not just the nice ones or the normal ones.

The call of the wild is in us. "We are human in good part because of the particular way we affiliate with other organisms. They are the matrix in which the human mind originated and is permanently rooted, and they offer the challenge and freedom innately sought... I offer this as a formula of re-enchantment to invigorate poetry and myth: mysterious and little-known organisms live within walking distance of where you sit. Splendor awaits in minute proportions." Back to our microscopic roots.

Meanwhile modern art, like modern man, is sometimes seen as anti-nature. It tends not to focus on life. It is disenchanted, mechanised, and – unlike earlier art – out of love with the growing world. This isn't entirely true. It can have its own nature poetry and myth. It is occupied creating mysterious and little-known organisms. But these life-forms are often strange. They are invented organisms. They use biomorphic elements up to a point – fluctuating edges, irregular but rounded, going in and out, curvaceous contours – but use them as material for new biological fictions.

So these creatures seems to have slipped the catalogue of nature. And it puts biophilia to a test. Are such synthesised life-forms still an extension of the nature family, and within its wide embrace? Or are these aliens beyond our universal feelings of life-love?

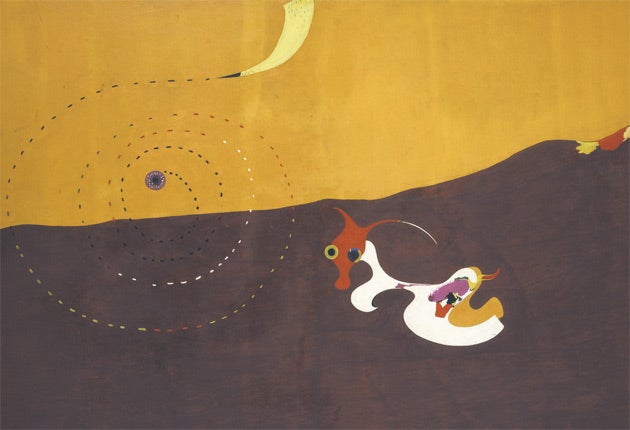

Joan Miró's Landscape (The Hare) certainly introduces (in brackets) a well-known animal. Its view shows a simple landscape, a chocolate earth under an orange sky. Some kind phenomenon, perhaps a comet, floats above the horizon, with a spiralling tail of dotted line, pursued inconceivably by a simple bird. But the most conspicuous and complicated figure in the scene is surely a kind of creature.

It is not an anonymous or abstract shape. It may not belong to any recognisable species, and without the title it probably wouldn't strike you as Lepus europaeus. Those arcing, whiskery "ears" are more like a snail's horns or an insect's antenna. Its bug-eyes and bulbous snout recall a seahorse. But it still has a creaturely aspect.

Go for a larger likeness, if you can. It has a body, with a head, fore limbs, rear limbs, a bottom, even a tail. Its whole stance has in fact echoes of a famous cave painting – the horned human image of The Sorcerer, discovered in the Trois Frères cave (or at any rate, as recorded in the drawing made by the archaeologist Abbé Breuil). This entity, glowing in white and red and orange and purple, could also suggest a lambent deep-sea creature, or again (overlook the head) a flowering.

It has a protean identity. Its fluctuating curvaceous coastline is calculated. It can take on various characters because its shape lets you pick out possibilities. It depends on what you pay attention to. Equally, you can ignore the potential organisms entirely. You can simply consider the contours of this form. What substances is it made of?

This shape could be a pool of a liquid, for instance. Some of its curves suggest an area of split drink, doodled around undulatingly on a tabletop – or perhaps pancake mix dropped into a hot pan. It is entirely fluid and malleable and passive. But some of the contours can suggest something else – a flat and sharp-edged sheet. It can be a blade. The fore limbs, say, curving round with a hook, look like a pruning knife. There are also inlet bays, which feel as if they've been carved out. The form is like a jigsaw piece or a painter's palette. Its form is both cutting and cut out.

Finally, there is the possibility of an inflatable, something rubber and blown-up. It can be clearly felt in the head and nose, but all over there are glimpses of a swelling balloon. And now the form acquires a three-dimensional existence, whereas the pool of fluid and the cut sheet were both flat. Each of these aspects brings out contrary kinds of matter, with contrary tactile sensations: unresisting, hard, squeezy.

On these terms, it isn't lifelike at all. Its ingredients appear mineral or man-made. None of them imply the stuff of life – and seeing it now like this, now like that, this form becomes an impossible object also. But then, Miró's The Hare is a multiple duck-rabbit. Within its form several creatures continue to coexist. Its organic contours are what yield its various non-organic possibilities. Everything changes into everything else.

But beneath all these roles there is still a basic form, a single blob, which doesn't have any firm identity but doesn't disintegrate either. It's like a bit of minimal living matter, the classic amoeba. The organism survives in a state of flux, a piece of pure creation. To that extent, it is life – and possibly lovable too.

ABOUT THE ARTIST

Joan Miró (1893-1983) was a maker of worlds. The Catalan painter became a modern-art version of Hieronymus Bosch. His cosmos is a phantasmagoria of insects, sperms, eyes, paper decorations, dots, body parts, turds, letters, stars. In the 1920s, his creativity rages. From 1940, he is stuck.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks