Alberto Burri: Form and Matter, Estorick Collection, London

The Italian war medic turned artist Alberto Burri proves to be a neglected master and innovator in a show of power and beauty

You might think imprisonment an unlikely spur to becoming an artist, especially if the prison was in Texas.

Not so for Alberto Burri, though. Burri, an Italian military doctor in the Second World War, was captured by the Americans in 1943 and interned in the small Panhandle town of Hereford, Texas. When he went back to Italy in 1946, it was not as a medic but as a painter; and not just as a painter, but as an Expressionist. Somewhere along the line – one assumes not in Texas – Burri had come across contemporary American art. He was to serve as a one-man emissary for Abstract Expressionism in Europe, Italy's answer to Jackson Pollock.

That, at least, is a version of events, although a look at Burri's work at the Estorick Collection in London suggests it is not necessarily the right one. If Black T, painted in 1951, has the scabby-kneed feel of a Pollock, The Stall, painted four years before it, certainly does not. In the year – 1947 – that Pollock painted Full Fathom Five, one of his trademark Jack the Dripper canvases, Burri was still making the kind of big-eyed Jungian images the American had dispensed with a few years before. So Burri became an abstract painter in Italy rather than in America, his progression from Expressionism to Abstraction running in parallel with American art history rather than imitating it.

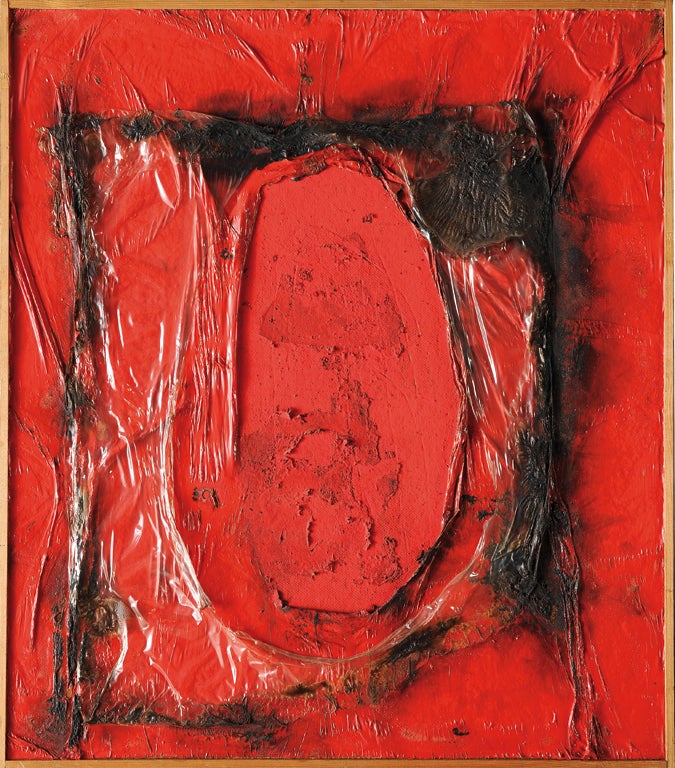

This might seem a niggling point, but it isn't. If some of Burri's Italian contemporaries caught the non-Italian imagination – Lucio Fontana is an obvious case in point – many, like Burri himself, did not. Only one of the works in the Estorick's show comes from a British collection, and that (Sacking and Red), has spent much of its time on a shelf in a Tate Modern warehouse. And yet Burri is as fine a painter as Fontana, and historically more significant. From the hessian sacking and charred polythene of works such as Red Plastic (1961) runs a straight line to Arte Povera; and that is a very important descent indeed.

So why the 60 years of British neglect? I'd guess that Burri initially suffered from being seen as either too American or not American enough, when in fact he was neither of those things: he was simply an original painter. Any resemblance to Pollock is coincidental; if Burri's works of the 1950s have a feel of Rauschenberg's Combines, they actually pre-date them. And then, of course, Burri was an Abstractionist a decade before it was possible to be one in Britain. In any case, we know far too little about him, which makes the Estorick's show a useful plug to a gap in art history.

Lest that seem dry praise, Burri is also a wonderful painter. Like much good art, the power of his work lies in its ability to be several self-contradictory things at once. A picture such as the Tate's Sacking and Red is entirely abstract, the harmonious interplay of a particular kind of carmine pigment Burri favoured in the 1950s, with the warm brown tones of sacking, the close-knit texture of canvas and the raw, broad weave of hessian. Beyond this, the picture both invites us to read a narrative into it and forbids us to do so. It seems, at first glance, like some kind of landscape – of Burri's native Umbria, perhaps, with its ochre and umber soil – and yet it is, just as insistently and at the same time, clearly just paint and fabric.

There is something else going on in these works, for which the most convenient word is "politics". For a couple of years around 1960, Burri made pictures by attaching iron sheeting to canvas, or to a wood base on an iron stretcher. The result – works with such bald titles as Iron and Black – are both made in a workmanlike way and about the workmanship involved. They have the titanic intimacy of ships, as though, in a gallery in north London, we somehow find ourselves brought face to face with the plated sides of a steamer. As well as any outside story they may call to mind, these images are about the story of how they were made – the whole of art boiled down to process, or, if you prefer, to the concept of work. They reduce the mystery of painting to a kind of labour, and raise labour to the status of art.

All of which makes Burri sound like an agitprop painter, which he insistently isn't. Bound up in his art is a fierce sense of beauty, even if it is not the kind we necessarily find easy to look at. He is a romantic artist, and an exceedingly good one. On various grounds, this show is really worth making a trip to see.

To 7 April (020-7704 9522)

Next Week

Charles Darwent finds himself dwarfed by David Hockney's Bigger Picture at the Royal Academy

Art Choice

Graham Sutherland: An Unfinished World – curated by George Shaw – does much to rehabilitate the neglected British Modernist at Modern Art Oxford (till 18 Mar). Brazilian Lygia Pape, 85 this year, gets a retrospective at London's Serpentine Gallery, with a central installation of gold threads stretched into shafts of light (till 19 Feb).

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks