Antony Gormley, White Cube, Mason's Yard, London

Antony Gormley has come to embody what we might think of as a "public" artist. You might think about popularity, or the populace when you think of his work: commuters zipping past the Angel of the North on the A1, or last year's One and the Other, his project for the Fourth Plinth in Trafalgar Square that saw members of the public standing on the plinth. He is popular, and perhaps feels that his popularity is looked down on by the art world. Is he really an artist of the people, then? Perhaps not.

This is Gormley's first exhibition at his commercial gallery, London's White Cube, for some time, and it's interesting to consider how his art works when it is not in a public space.

On the upper level of the gallery are several cast-iron sculptures with figure-like proportions. One approaches them as though they are human, because of their size and scale, but they are, in fact, constructed of iron blocks and cubes. Tetris men, Meccano men, built from only straight lines. Robot men constructed using architectonic principles – they are more like buildings than people. Each figure has had some element or other emphasised or stretched: a long nose, arms like tables, or a giant, towering head. They look aged and rusty, as though they have been left to age in the rain outside a corporate city office, and, frankly, it's not too difficult to imagine one of these stood outside an office teeming with hedge-funders in the city. And I mean this in a bad way.

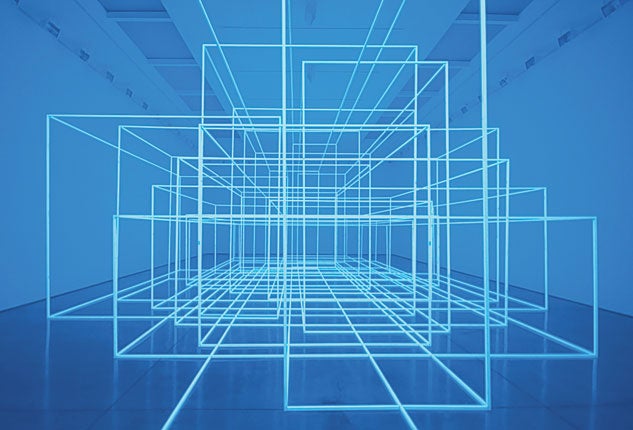

Downstairs is a little better, with Breathing Room III (2010). This is obviously meant to be the showpiece: the installation that incites gasps and excitement – even fear. In the darkness, empty, intersecting frames covered in glowing phosphorescent paint fill the gallery space, and illuminate it as though it were a virtual, computer-generated atmosphere. The gallery appears like a glowing grid. As the eyes adjust, and you walk around the gallery your perspective shifts, taking in the cold, Tron-like atmosphere of seeing architecture described this way.

Both of these installations suffer from what might be termed a lack of humanity. When Gormley is at his best, as with his sculptures of silent human figures on top of London rooftops, Event Horizon, that have recently transferred to the New York skyline, he brings us into contact with still, benign, ageless presences, that seem to meditatively observe us. The problem with this exhibition has nothing to do with populism. It's that he is often shown up by artists who deal with similar themes but to greater effect. Miroslaw Balka, another artist who has shown in this same White Cube space in recent years, also employs his own body to scale all of his work, also creates fear in his uses of space and architecture and also reminds us of our human bodies and our humanity. These Gormley sculptures and installations, by comparison, have a dead, technical quality, as though a mathematician has attempted to understand what a human is by dividing it up into geometric chunks.

Without Gormley's usual public, he looks nothing like an artist of the people.

To 10 July (020 7930 5373)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks