Charles Darwent on Ellen Gallagher: AxME - The dog ate my homework, Miss Gallagher

Why does this highly-rated American artist ask so much of us before we even look at her work?

Last week I spoke to a gifted young painter, a Jerwood Fellow, about his work. The conversation went like this. Me: “The two small pictures are particularly strong. I really like them.”

JF (alarmed): “Uh, I’m not sure ‘like’ is a word that can be used in critical discourse these days.”

So it goes. Once upon a time, long, long ago, there was nothing wrong with work that pleased, in whatever way it contrived to. Then someone invented critical theory, art schools became university departments, and pleasure went out of the window. Good painting might do a whole thesaurus of things — ironise, deconstruct, conceptualise, “reference its own process”, etcetera – but it must on no account be likeable.

I have no doubt, by these lights, that Ellen Gallagher is a very good painter. The 47-year-old American is best known for her canvases, although, this being 2013, she also makes films and sculptures: one, Jungle Gym/Preserve, is in the new show of her work, AxME, at Tate Modern. There is nothing wrong with making art in different mediums – see Michelangelo. But it is the idea of Gallagher as a painter, of the kind of painting she does, that bothers me.

Let’s start with Double Natural (2002). This vast, yellow canvas, perhaps 7ft high and 10ft wide, is Gallagher’s best known. On it are pasted, in a grid 33 squares wide and 12 high, advertisements and cuttings from American black lifestyle magazines. (Gallagher’s father’s family came from Cape Verde.) All of these offer perfectability of a kind, or at least an idea of self-improvement. One woman beams at us from under a headline that says, unconvincingly, “I Am Happy”. Another asks, “Do you want men to OBEY YOU?”, while a third advertises an Amazing Liquid That Removes Corns.

It is hair that is Gallagher’s particular focus, though, as it is of the small ads she uses. The majority of these are for hairstyles or hair products. To these the artist has added plasticine hairdos – straightened bangs, cornrows, dreadlocks, flicks – moulded by hand and painted yellow. Gallagher has also blanked out her subjects’ eyes, turning them into zombies. Her point seems clear. Black women are sold a dream of white womanly perfection. She has taken that process to its deadening extreme by turning her women blonde.

To say that Double Natural is dislikeable is to state the obvious. Its subject – the exploitation of racial insecurity for commercial gain – is not a pretty one, and Gallagher’s image would have no business being pretty. But the problem is that it isn’t anything else, either. Other than an immediate hit of macabre glibness, Double Natural just doesn’t deliver. The longer you look at it, the less you get back. Vacuousness in art can be extraordinarily powerful: Andy Warhol made an entire career out of it. But Gallagher’s painting isn’t empty in a good way. It is just empty.

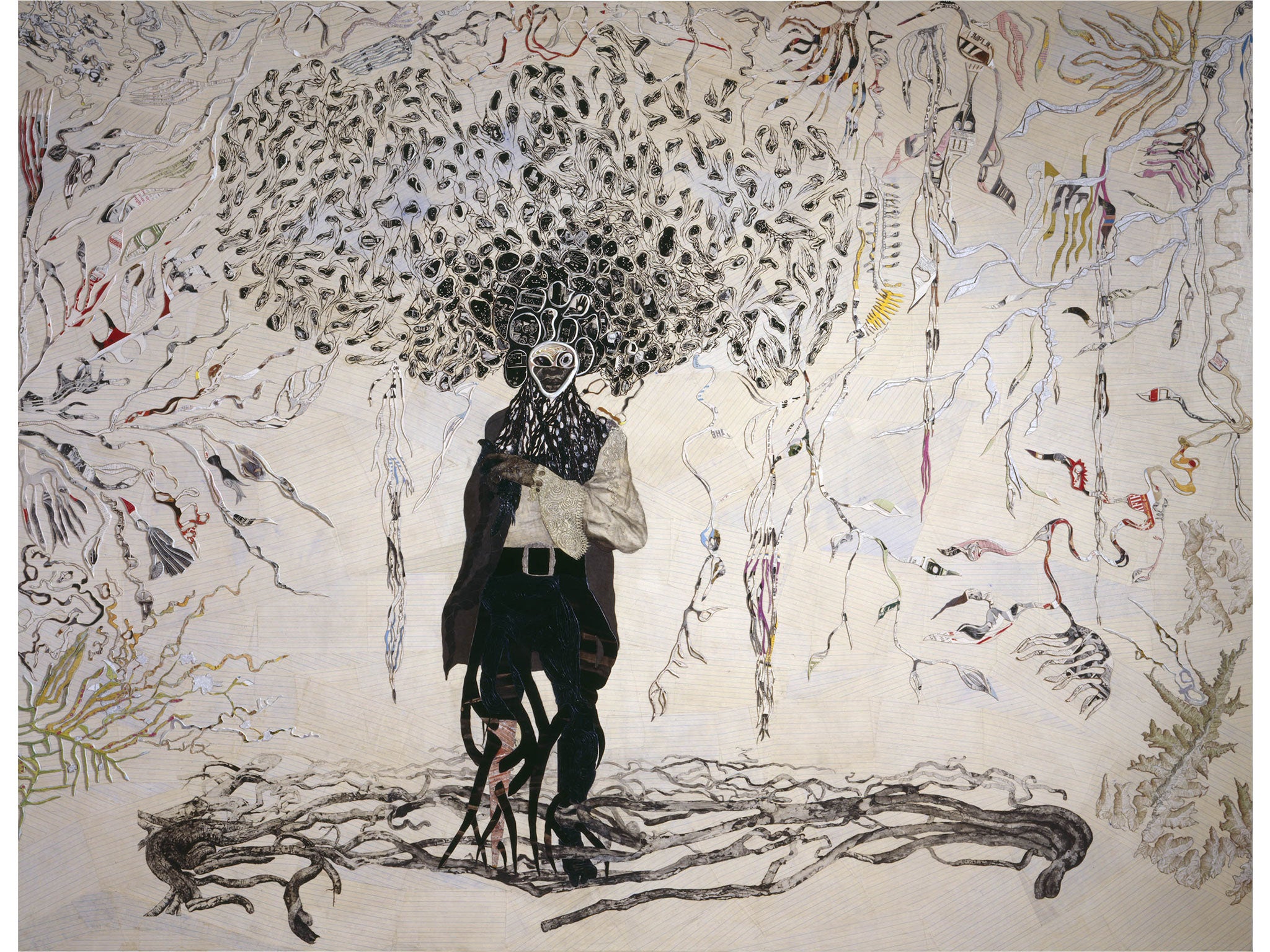

Let me see if I can be clearer. Another work in this vast, 11-room show is called Bird in Hand. It, too, is vast. Like many contemporary artists, Gallagher has created her own myth-world, one figure of which is a one-legged tap-dancer called Pegleg. (Pegleg actually existed — one of the ads in Double Natural is for his show.) In Bird in Hand, he mutates into a pirate, his hair and half-leg doodling out to fill the canvas in tendrils that might be seaweed.

Gallagher is part of her own mythology. Prior to being an artist she studied marine biology, and did research into pteropods. The many works in her Watery Ecstatic series, given a whole room in this exhibition, start from an interest in sea-life – eels, urchins, octopi. The pictures are largely in watercolour and cut paper, and, as compositions, appear less to evolve than to mutate. You can see the reasoning. Life starts at Point A and wanders off where Darwin takes it: so why not art? Bird in Hand grows, pictorially, out of Gallagher’s own history and interests.

But does that make it a good painting? The abstract works of the Jerwood painter I spoke to stood on their own as images: you didn’t need to know his life story or theories on art to respond to them. To get Gallagher, you have to have done your homework. Her art is about understanding, not seeing; when she paints, she paints incidentally. Any other medium might have done – actually, her films seem to me far better than her canvases (Murmur: Super Boo is annoyingly unforgettable). But then many people disagree with me, and you may well be one of them.

To 1 Sep (020-7887 8888)

CRITICS' CHOICE

Small is beautiful: Calder After the War at London’s Pace gallery exhibits the American sculptor’s complex mobiles (above), made out of pieces small enough to post to his friend Marcel Duchamp (till 7 Jun). At the Ingleby gallery in Edinburgh, Garry Fabian Miller: The Middle Place reveals the changes in light, colour and atmosphere on a fixed line in the horizon, looking out over the Severn Estuary, plus more recent, camera-less light works on the theme of horizons.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks