John Tunnard: Inner Space to Outer Space, Pallant House, Chichester

Forgotten master of a lost universe. His work is in major collections worldwide and he was the equal of more famous contemporaries, but Tunnard has been overlooked

Among other wars fought in the 1930s was the one between Surrealism and Abstraction. Here, as on the Continent, lines were drawn. On the surrealist side lay Roland Penrose, painting dream-like, figurative pictures that smacked of his mentor, Max Ernst's. Leading the abstractionist camp was Ben Nicholson, back from Mondrian's studio in Paris and making cool, geometric white wood reliefs. Between these two lay territory warmly contested by combatants who had a confusing habit of changing sides.

In the catalogue to an exhibition called Living Art in England, held in January 1939, Henry Moore lists himself as a surrealist, while John Piper, hedging his bets, is "a cubist, abstract, constructivist, surrealist independent". John Tunnard, the subject of a compelling new show at Pallant House in Chichester – Inner Space to Outer Space – is down as an abstractionist.

Which makes you wonder about the wisdom of art terms, and, perhaps, of art history. Quite why we know the names of Penrose and Nicholson but very possibly not that of Tunnard is a matter for debate. Tunnard is a more interesting, more complex and better painter than Penrose, but did not, like him, have the good sense to set up the Institute of Contemporary Arts.

Then again, Tunnard did himself no favours by moving to Cornwall – not, like Nicholson, to arty St Ives but to Cadgwith Cove on the Lizard peninsula. His pacifism in the Second World War may well not have pleased Sir Kenneth Clark, then commander-in-chief of British art.

All of which is a shame. In 1939, Peggy Guggenheim gave Tunnard a show at her London gallery, Guggenheim Jeune. Remarking on his elaborate tweeds and uncanny resemblance to Groucho Marx, Guggenheim also compared Tunnard's work, favourably, with that of Kandinsky and Miro. Alfred H Barr, founder of New York's Museum of Modern Art, bought his pictures for the MoMA collection, where they were seen and admired by Mark Rothko. That Tunnard should have fallen so far from fashion since his death 40 years ago seems deeply unfair, the only compensation being the pleasure of rediscovering him now.

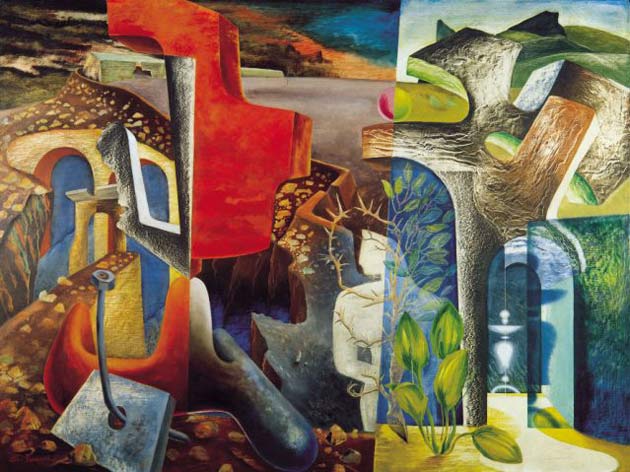

In 1937, Tunnard showed in the Surrealist section of the Artists' International Association; a year later, as we have seen, he was a self-declared abstractionist. A work of 1939, called Fulcrum, shows how both of these things could be true. Fulcrum's biomorphic shapes and Gabo-like strings are abstract in being imagined, but are also realistically modelled. The lozenge-like form to the left of the picture is clearly vaginal. What really surprises in works such as this and Man, Woman and Iron, though, is their technique.

Early on in this show, Tunnard hits on a stippled surface that looks textured, grainy to the touch, but which is entirely flat. Even up close, the effect feels photographic, as though the artist has found a way to take pictures of rough concrete with a camera and then transfer the image to canvas.

Quite how he did it, I cannot say: my best guess is that he laid wet paint on dry and, before the fresh layer had set, partially wiped or brushed it off. At any rate, I can not think of another artist who makes a textural effect so much his own, nor who more successfully plays off the painted illusion of space against planes and recessions scratched into his paint.

But Tunnard is by no means just a skilled technician. A feel for pattern might, to an extent, be explained by his earlier career as a textile designer. It does not account for his genius as what you might call a psychogeographer – a charter of odd terrains that appear to have three-dimensional depth but which are also clearly planar and flat, whose floating forms are prone to the laws of a physics entirely their own. It is the accuracy of this mapping that amazes, the sense that Tunnard doesn't just see these worlds but has walked through them.

In a sense, his career played itself out backwards. Starting in the realm of the imagined real, it ended in the really unimaginable. The Nash-like lyricism of Tunnard's early art was always touched by something dark. From the 1950s on, it found that darkness imitated by life – by technology that exploded French H-bombs on Pacific atolls or sent back echoes from deep space to the radar dishes at Goonhilly Downs, near the artist's home. All these figure, directly or obliquely, in the last pictures in this exhibition, works that manage to stay both resolutely modern and grounded in themselves. We really should know more about John Tunnard. With luck, this show will mean that we do.

To 6 Jun, Pallant House, Chichester (01243 774557)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks