Keith Vaughan, Pallant House, Chichester

Here is a fine painter at his finest – whose pictures, despite their bulk, show humanity at its frailest in an overwhelming landscape

The seated man watching the Musicians at Marrakesh is – at least in the mind of Keith Vaughan – the artist himself looking on and listening in. The massive back, bottle-top head and wayward limbs are grey and lumpen. The musicians, by contrast, are glowing, creamy and luminous: the ochre drum, a radiant little sun, the cross-legged player as neat and focused as his observer is awkward.

Vaughan cuts a sad figure in the history of British modern art too, disappointed with himself, despite the impressive body of work, the CBE, and the many successes he lists to himself in his extensive, revealing diaries, as he attempts, fruitlessly, to talk himself into living. At 65 took his own life, thoughtful and analytical to the end. He had nothing to reprove himself for: the exhibition that marks the centenary of his birth, at Pallant House in Chichester, near his birthplace, Selsey, celebrates an artist who absorbed many influences but had his own distinctive voice.

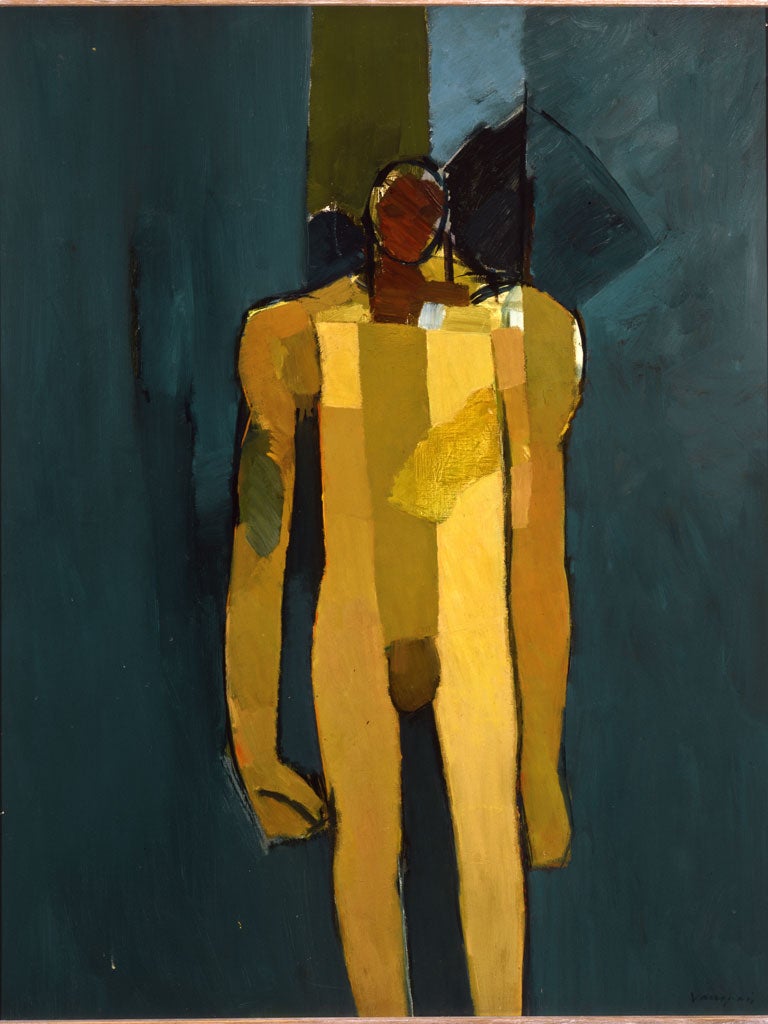

His quest was to "create an image without any special identity, either of gender or number, which is unmistakably human; imaginative without being imaginary". So the male(ish) models, lovers and friends who people his pictures show more humanity than manliness, their condition one of frailty, despite their bulk, in a landscape so powerful it can swallow them whole.

The crouching specimen in Man in a Cave could be both born of the rock and returning to it: in 1943 this is Vaughan's response to the Second World War. A conscientious objector, he served in the Pioneer Corps, taking a fat sketch book and an unbreakable bottle of ink. Thrown together with other intellectuals, he became not only a perceptive chronicler of his own life, but a friend of writers and a contributor to their groundbreaking periodicals. He was a perfect fit for book-jacket illustration, outstanding examples of which are showcased here.

The subtitle of this exhibition is Romanticism to Abstraction, and, by the Fifties, the landscapes that make up the final room of this captivating show are breaking up into impenetrable blocks of colour, Black Rocks and Beach Huts, Whitby Bay (1955) dominated by dark chunks that tower over a gleaming white hut. By 1962 and Cenarth Farm, colour is breaking off in clumps, the squarish green fields puffing up into the sky.

And yet in January 1954 he has declared firmly for figurative painting: "Now I have my instrument, but what to play on it," he asks of himself, after a show whose very success made him doubt his worth. "Abstraction seems the way out for most other painters. But I cannot regard it as a solution."

And yet the figure/landscape balance tips inch by inch into abstraction. From the outset, Vaughan painted beach scenes and placed his monumental forms in Bacon-like empty rooms or in passive open spaces, his nudes almost as androgynous as the two faces kissing in the moon that has fallen to earth in Night in the Streets of the City. (The actor Michael Redgrave bought it in 1943.) Even painting his lover Johnny Walsh for the magnificent Standing Figure, Kouros (1960), in place of sensuality he invokes an antique classicism, the model's arms held rigidly to his static sides, his hair two severe stripes instead of a luscious tumble of ringlets.

Such references to other art, ancient and modern, punctuate the whole show: here is Matisse, lending his bathers, and before him, Cézanne. Here too are Sutherland, with his wartime destruction, and Picasso, with his interwar neo-classicism.

Declaring that a painter has just one basic idea for life, and that his was the human figure, Vaughan clings to man in the Sixties. But man loses his individuality in the series of nine Assembly of Figures that distils the essence of what it is to be human. In the first of the two shown in Chichester, two burly nudes peer at the ground as a third lifts a restless arm and leg: is it dance or despair? So often a hand reaches into the air, clutching at a place in the cosmos. By 1964, in Assembly of Figures VII, the rank of torsos has fused together and into the landscape like standing stones, a head here, an arm there, the synchronisation complete. Here is a fine painter at his finest – and still racked by self-doubt. Here, too, is a worthy and moving celebration of an unfashionably self-doubting artist.

To 10 Jun (01243 774557)

Art choice

Get a new perspective on Joan Miro at the Yorkshire Sculpture Park, where his art comes to startling 3D life in the simply titled Miro: Sculptor. But there's no rush, the show's on till 6 Jan 2013. All About Eve takes in the career of photojournalist Eve Arnold, from snaps of Marilyn Monroe to Malcolm X. At London's Art Sensus gallery (till 27 Apr).

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks