Miro: Sculptor, Yorkshire Sculpture Park, Wakefield

Everyone knows Miro as the artist of big, colourful canvases – but this survey of his sculpture gives him another dimension

Unless, unlike me, you are a Miró specialist, you would probably not take Souvenir de la Tour Eiffel for the Catalan master's work. There are several reasons why not.

One is that we tend to think of Joan Miró as a painter and this is a sculpture – a bronze, although it appears to be, and was, modelled from bits and bobs the artist had lying around in his studio. The tower of the work's title is a split cane hat-stand, the tantalus waving from the deep-sea-fish-thing on top of it a wooden pitchfork. The fish's body is harder to get. As it happens, it is the mannequin-head of Groucho Marx, the comic's tell-tale features, face-up, shrouded in bronze cloth; the open aperture of its neck forming the creature's gaping mouth.

If you allow that Souvenir de la Tour Eiffel is by Miró after all, then it is clearly an early sculpture, done in the mid-1920s when he was in Paris and working as a fully-paid-up Surrealist. But no. This strange hybrid, an assemblage of found objects reeking of Duchamp and 1927, was made in Mallorca in 1977 when Miró was 84 years old.

So here is the problem. For most of us, Miró is not just a painter but a painter in old age – the one who made those big, colourful, likeable canvases, the artist we know from the tail fins of Iberia jets or the logo of the Spanish Tourist Board. The leap from that Miró to this – the maker of Souvenir de la Tour Eiffel, which is currently on show at the Yorkshire Sculpture Park – is a wide one. And yet Souvenir de la Tour Eiffel is entirely typical of Miró, not least in its being sculpture.

At 19, and in the teeth of his silversmith father's opposition, Miró enrolled at the Escola d'Art in Barcelona. His teacher was Francesc Galí, a proto-Modernist who had already worked his way through Post-Impressionism and Symbolism and would end up as a Cubist. For all that, Galí was a rigorous draftsman.

Young Joan was encouraged to draw from objects which he had handled blindfold; to work from touch rather than from sight. In middle age, he recalled the experience. "Even today, 30 years later," Miró said, "the effect of this touch-drawing returns in my interest in sculpture: the need to mould with my hands – to pick up a ball of wet clay like a child and squeeze it. From this I get a physical sensation that I cannot get from drawing or painting".

Standing on the terrace above the sculpture park's formal garden, these words seem oddly apt. Wafted on the wind is the unmistakeable smell of pigs, calling to mind the other great influence in Miró's early life. When he moved to Paris in 1918, the Catalan took with him paintings begun on his parents' farm at Mont-Roig del Camp. These contained the seeds of what was to be his 70-year vocabulary as an artist – maize tassels that morphed into starfish and then into stars and then became maize tassels again; the bulbous shapes that were eyes or breasts or buttocks, or possibly tomatoes, or all four.

More even than Picasso, Miró invented his own cosmology, a world of things to each of which there was a season, and then another and another. What we see in Souvenir de la Tour Eiffel – in its back-of-the-attic materials, its back-to-the-Twenties style – is not so much recycling as replanting, less Miró the Surrealist than Miró the farmer. This is true not just of the sculptures as a whole but of each of them, however unalike they seem.

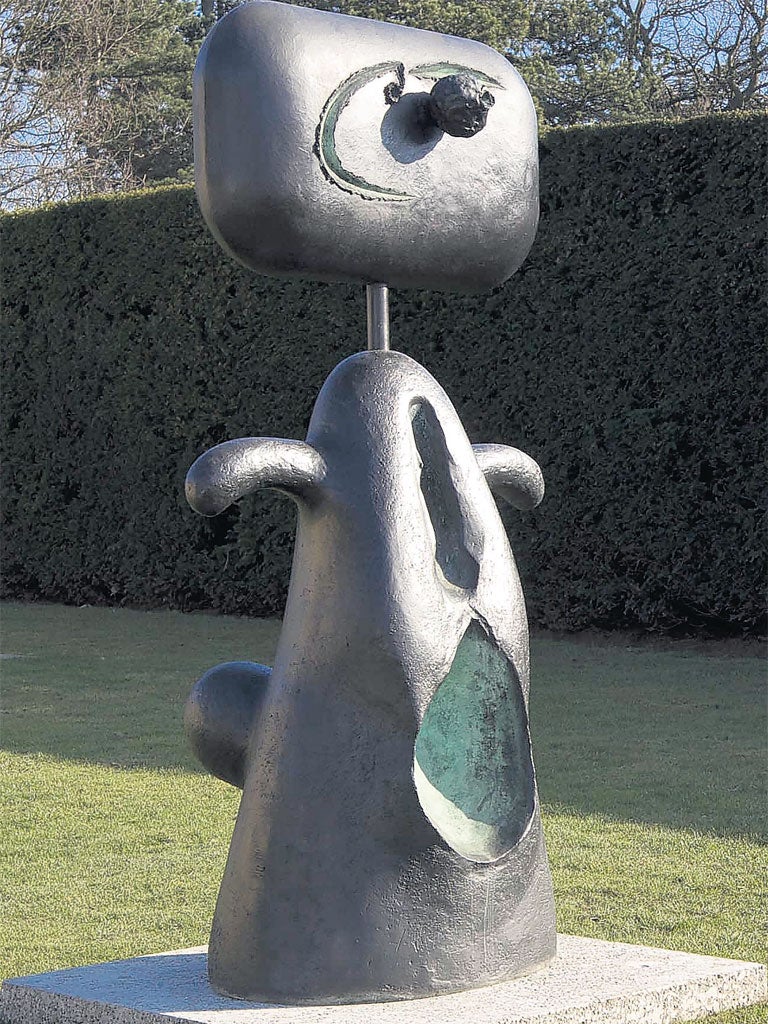

Here, on the terrace, is Femme, much more Miró than the Tour Eiffel to eyes used to his late painting. Femme is two metres high, cartoony, child-like, a rectangular head stuck on a conical body, bulbous protuberances and a tear-shaped recess reading as buttocks and a vagina. Then again, these may simply be olives and a leaf from Mont-Roig. The leaf and the olives may even be painterly, since these forms also appear in Miró's two-dimensional works. The incised swirl in Femme's face, a lopsided grin in bronze, has the feel of brushstroke. It finds its inverse in another, smaller Femme in the sculpture park's Undergound Gallery, a skinny, graphic, wiry bronze that would fit nicely into its bigger sister's smile.

Positives and negatives; sculpture that looks like painting that looks like sculpture; late work that seems early, and vice versa; body parts that move about – eyes in groins, dicks as arms – then change species or biological kingdom or dimension, or alter their meanings, are symbolic one moment and gestural the next. All these things are in the Yorkshire Sculpture Park's fascinating Miró show. They allow us to see him not merely as a sculptor but as a creator of universes, a maker of worlds.

To 6 Jan 2013 (01924 832631)

Art choice

Johan Zoffany, often overlooked 18th-century German painter of British royalty, enters the spotlight at London's Royal Academy, and he's cheekier than you'd expect (to 10 Jun). At Tate Britain, you can trace the influence of Picasso on British artists from Wyndham Lewis to Hockney via Francis Bacon – or just bask in the glory of the Picassos (to 15 Jul).

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks