The Encounter, National Portrait Gallery, London, review: Old Master drawings have a breathing immediacy

A compact show brings together drawings from the Renaissance to the Baroque eras which seem to eyeball the viewer

Leon Kossoff once told me that every morning of his life he needed to begin the studio day by drawing – in order to prove to himself, yet again, that he still had the capacity to do that which underpinned everything. Drawing was that important to him. It was the guarantor of everything, the floor upon which the entire superstructure rested.

His words replayed themselves, gently, as I wandered through this pleasingly compact show of 49 Old Master drawings, which turns in a circle, secretively low-lit as befits the works' fragility, through three galleries. The title of the show itself – The Encounter – is startlingly abrupt, as if we are being unceremoniously bundled into someone's presence. And so it proves to be.

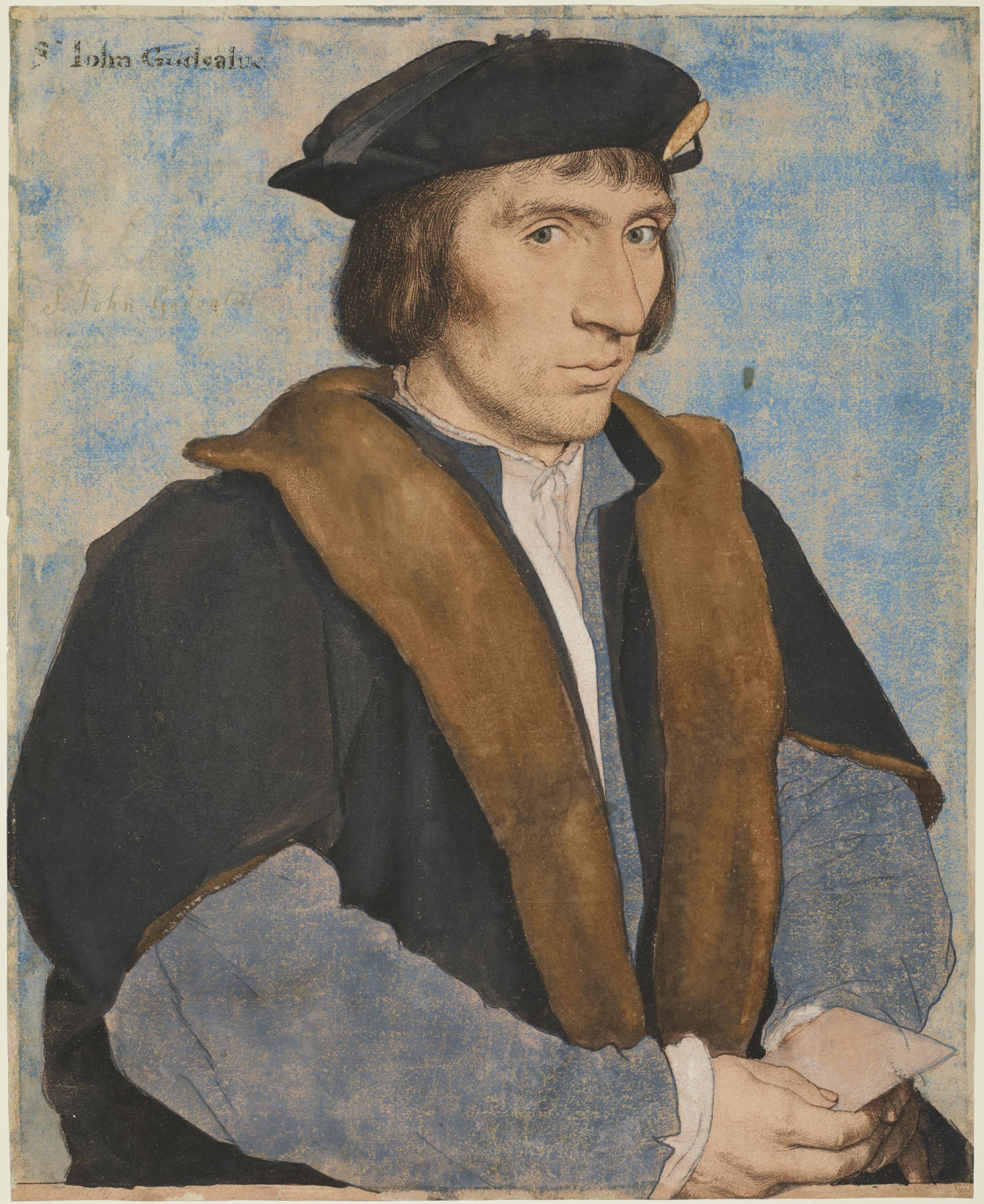

These are European portrait drawings, not paintings, from the Renaissance to the Baroque, which means from the middle 1400s to the middle 1600s, by the likes of Leonardo, Pontormo, Dürer, Parmigianino, Holbein, Clouet. They have a breathing immediacy about them. We feel we are but a warm breath away, even when we stand removed. They buttonhole us, just as the sitters have themselves been buttonholed. We are eyeball to eyeball.

The objects themselves – which range in medium from chalk to pastel, from ink to metalpoint – are quite distinct as a species from paintings. A painting is what comes later – a great rhetorical flourish perhaps in the case of a Van Dyck or a Rubens. These drawings, usually fairly small, are what happens before a painting is executed. Some of them may have survived because they came to be regarded as too precious to dispose of. Others may have clung on thanks to Lady Luck, who often acts with unusual benignity. We often simply do not know.

The making of such works is often quick and spontaneous. The capturing of a likeness. The seizing of a character. On the wing. Fleeting. Often the sitter, we sense, feels trapped by the scrutinising eye. The sitting – such as it is – may not have been pre-arranged. Happenstance may have caused the young man to call at the Bologna studio of Annibale Carraci in the 1580s.

Some of them reveal an artist somewhat different from the one with whom we thought we were familiar. The page of Rembrandt drawings is unusually rough and loose. Parmigianino draws so sweetly, without any hint of mannerist distortion. Durer's curious double study of a naked female form looks a little mechanised or puppet-like, as if that imperious bully André Breton may have spoken to him in a dream. Matters are seldom brought to a fine state of resolution. There is indeterminacy, a refusal to slam the door, everywhere. The predilections of the twentieth century are upon us long before it ever happened.

The Encounter is at the National Portrait Gallery till 2 October, npg.org.uk

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments