Unscrolling the masterpieces that were made in China at the V&A

The UK's first major exhibition of Chinese paintings since 1935 reveals that far from being monolithic, the art of the country is highly individualistic, propelled by artists with their own distinctive styles

It has taken a long time for a major historical survey of Chinese painting to be held in Britain. Not since 1935, before the Japanese occupation and the communist takeover, in fact. You can blame it on Mao and his Cultural Revolution, which deliberately obliterated the idea of courtly or individual artistry and rejected past painting as part of a despised past. But then you could equally blame it on a British imperialism which invaded China twice and forced China into taking opium in return for its goods, a memory that blighted British relations with China for a full century after. The burial artefacts of 4,000 or 5,000 years ago have come to Britain in a post-Mao demonstration of China's ancient culture but very little of the paintings of the last couple of millennia when China produced some of the most sophisticated art of Asia.

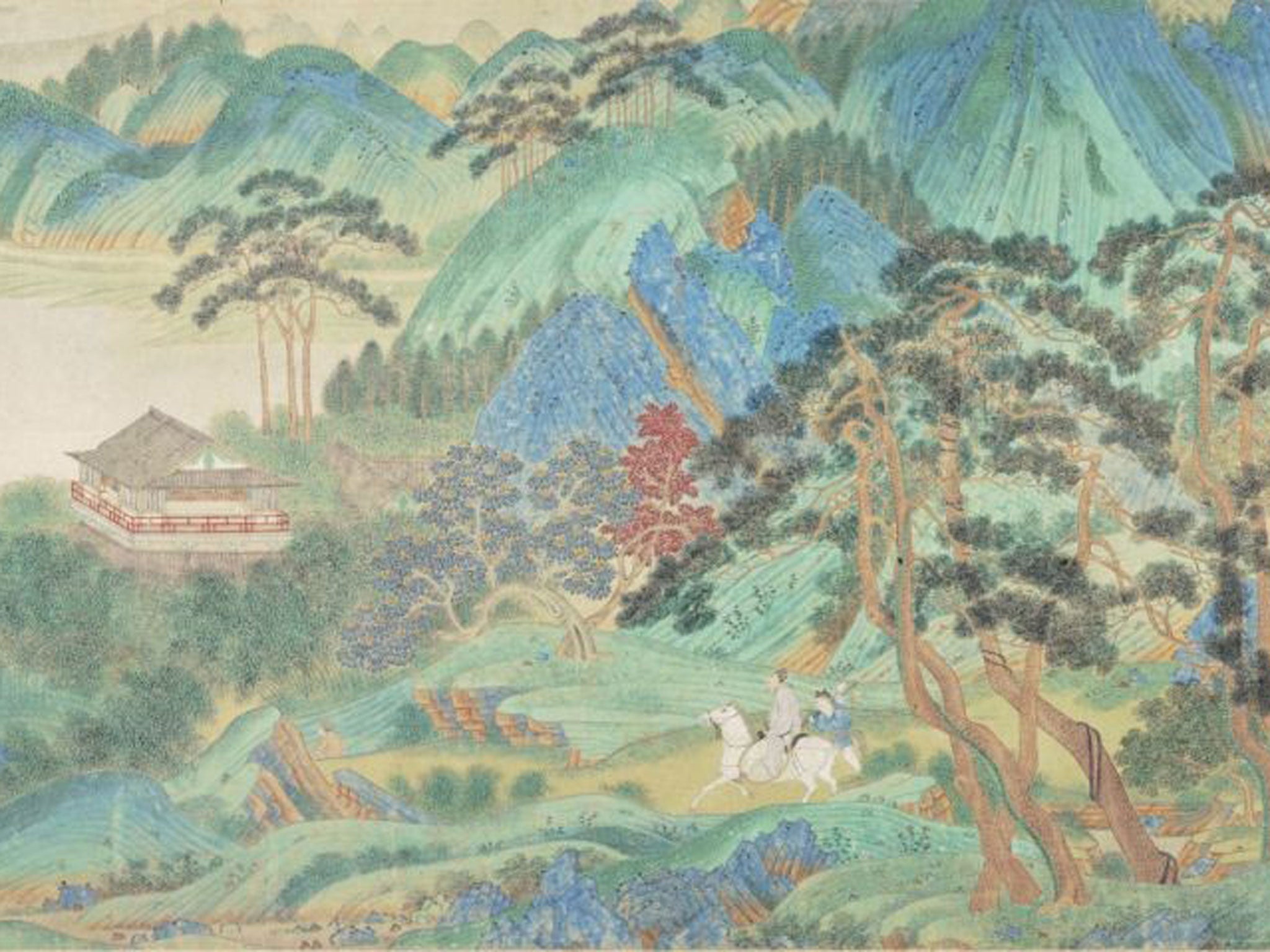

The Victoria and Albert Museum's magnificent show Masterpieces of Chinese Painting 700-1900 puts an end to that. It's an extensive display, covering all the periods from the Tang to the Qing dynasties. Its title is no vain boast. This is a gathering of great works, a good portion of them in the form of scrolls which are rarely unrolled for public gaze. Like the outstanding The Genius of China exhibition of 1973, which first opened up the glories of China's ancient cultures being dug up by its archaeologists, with the flying horse and jade princess, this is an experience that you can't afford to miss.

The theme of the V&A show, in a sign of changing political times, is the individualism of Chinese painting. Most of the discussion about Chinese art post war, and much contemporary work, is about uniformity and control from the top down. The impression has gained hold that the art of the Chinese is somehow monolithic and always has been. Not so, the curators argue, the art of the country has traditionally been highly individualistic, propelled by named artists who have gained their own reputation and influenced styles with their personalised work.

It's a thesis that underrates the importance of imperial patronage on art styles and sidesteps (nationalist politics being what they are) the influence of Japan and the Muslim worlds on Chinese art. It certainly doesn't apply to the first section of the show, in the Tang dynasty from 618-907, when Buddhism dominated the iconography of art with anonymously painted banners on silk and handscrolls. But even here you can see some of the distinctive Chinese features of round faces and flowing robes coming into play. With the coming of the Song dynasty in 960 and the reunification of China, however, you are into a different artistic world.

Quite why the dramatic change, and whether it had earlier beginnings, is not explained. But the difference is dramatic. Landscape becomes a major theme of painting, the styles become more individual, perspective comes into play. Even in the paintings here of the 10th and early 11th century, you have the full array of protruding mountains, the bare trees of winter, the mists of morning and the lake waters merging into the sky which make Chinese painting so instantly recognisable. In the paper handscrolls the details are drawn in fluid outline and precise detail, while the figures in the silk hanging scrolls are painted with often caricatured faces and personal expressions.

A hanging scroll by the late-12th-century painter, Zhou Jichang, of Buddhist disciples dropping alms from the clouds onto the indigent below, Luohans Bestowing Alms on Suffering Human Beings, is an extraordinarily touching vision of grace and destitution, with the poor below, painted with fierce realism, shivering in their tattered clothes and scrabbling for the alms.

Landscape changes with the artist and with time. Mi Youren, who gave his name to a whole style of wet ink brush mark paintings (“Mi dots'), is here represented with an ink study on paper, Cloudy Mountains, that would have done credit to the French Impressionists, while an early 12th-century painting on silk by Li Gongnian, Winter Evening Landscape is a masterpiece of atmospheric rendering of fading light and distant hills set off against a precise foreground of leafless trees.

The Mongol invasion and the imposition of a new dynasty, the Yuan, in 1279 disrupted the politics of China but seems to have given a new energy to its art. Melancholy became a leitmotif as the scholar painters of court lost their jobs and retreated to individual haunts in the country. The ink painting of “literati” artists of the South, translating the sentiments of poetry into visual terms, gained new relevance as artists became contemplatives.

Some of the moodiest works of world art belong to this time as artists created works as gifts for friends and tried to capture the fleeting moments of time and place. The fragility of feeling is caught in the thin ink in which ghosts and monks are depicted in works attributed to Shi Ke, Zhiweng and (most humanly) Muxi. The sense of loss is expressed in exquisite ink renderings of plant and branch by Zheng Sixiao (Ink Orchid) and Wang Main (Fragrant Snow at Broken Bridge).

Chinese painting never quite recaptured that quality of elusive delicacy again, although artists of the 17th and 18th centuries made very deliberate attempts to recreate old styles and to paint traditional themes in new ways, and with considerable effect. Colour becomes more important, the compositions more emphatic and the figures more precisely drawn. The Ming period (1368-1644) saw a revival in courtly patronage and broader commissions. Portraiture takes its place in the show as does pastel colours in landscape. A touching self-portrait by the painter Tang Yin (1470-1523) pictures the middle-aged artist, returned to Suzhou in shame and humiliation after being falsely convicted of bribery in Peking, sitting in his chair beneath a paulownia tree, thinking of past hopes and present loss.

If there is no falling back in creativity, however, there is a certain constriction of subject. Old subjects rule but with broader brush strokes and more complex composition. Western influence comes to bear in the greater realism of the figurative art and in the perspectives of the topographical paintings. But it appears as lessons to be absorbed rather than a style to be copied.

There is one exception to this traditionalism and for me it is the climax of the show. Bada Shanren's Flowers on the River, on loan from the Tianjin Museum, is an enormously long ink paper handscroll painted by the artist – prince and monk – in 1697 when he was 72. Its motif is the lotus in bud, in flower and in decay. Its mood is at once meditative and joyous, it's brushwork expressionist and free as only a man approaching old age can encompass. I can only compare it to the later works of Titian and Matisse in the bravura pleasure of an artist let loose from the bonds of craft to imagine at will.

It's a sad comment on Chinese art today – bold and brilliant although some of it is – that, such has been the communist dislocation the country's past culture, contemporary artists have largely looked to the party populist iconography of the communist era to express their individualism. There is very little conversation with past masters of the kind that you see in Picasso or in recent generations of art school educated young Western painters. It is an even sadder comment on ourselves that it has taken nearly 80 years to produce an occasion like this to experience one of the world's great painterly traditions.

The V&A has gone far and wide for the exhibition, including the provincial museums of China, Japan and the major museums of the US and Europe. As a roll call of great artists it is hard to see it bettered, as an array of masterpieces it can't be.

Masterpieces of Chinese Painting: 700-1900, V&A, London SW7 (020 7907 7073) to 19 January

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies