‘Nineteen Eighty-Four’: How the dying George Orwell wrote his searing totalitarian dystopia on a remote Scottish island

The influential writer worked on ‘The Last Man in Europe’ from the wilds of Jura riddled with ill health, retyping his manuscript between bouts of fever and bloody coughing fits

George Orwell’s American publisher liked to say that Nineteen Eighty-Four’s title was arrived at by the author simply reversing the final digits of the year in which he had written it, anticipating a not-too-distant future in which brutal totalitarian superstates ruled the world.

The explanation is convenient but was never confirmed by Orwell, whose work did not actually arrive in print until 8 June 1949, a date that means this weekend marks seven decades since the rebellion of Winston Smith against Big Brother and his nightmare society of thoughtcrimes, 2 + 2 = 5 and Room 101 was first put before the public.

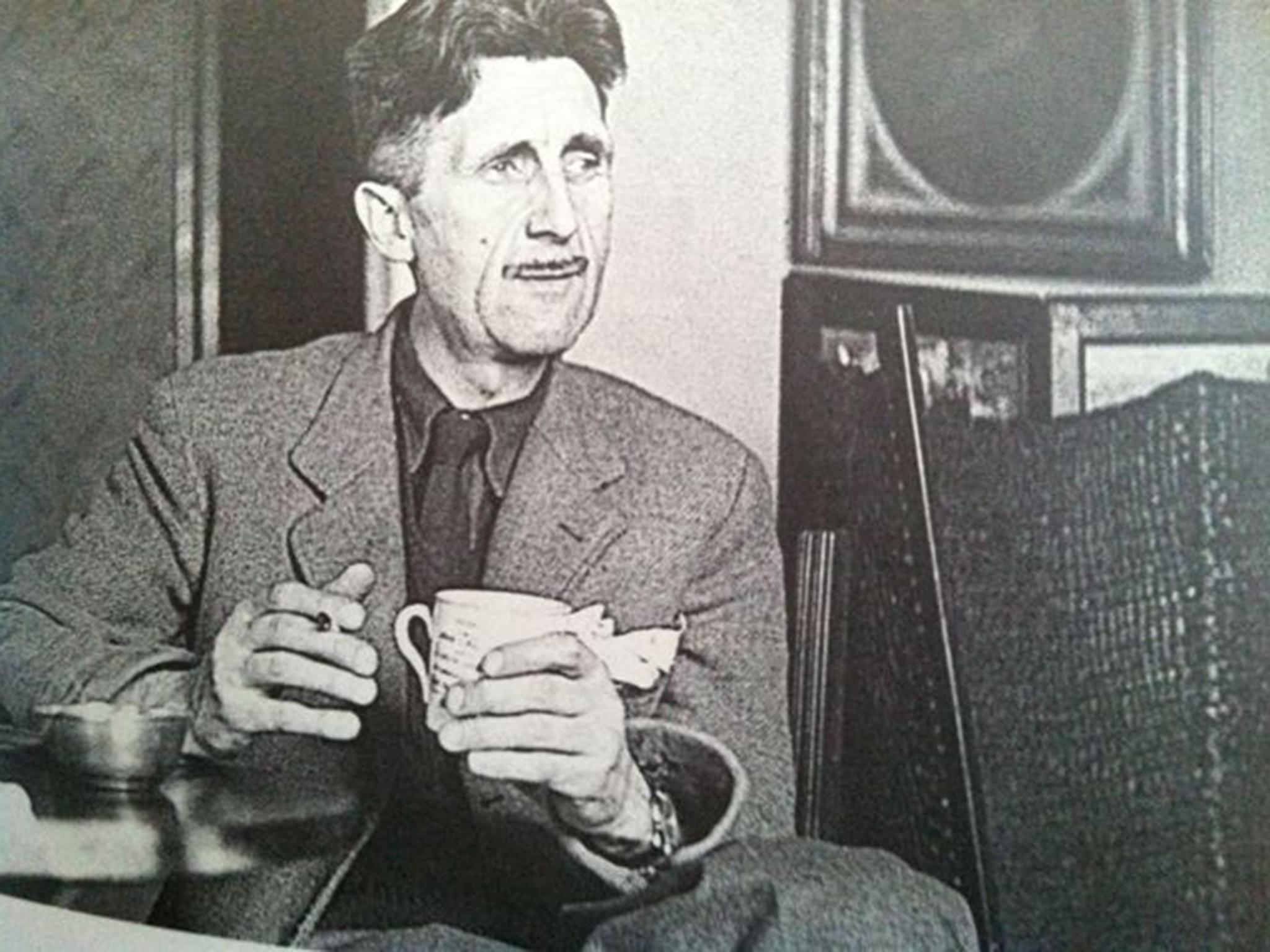

Orwell – real name Eric Arthur Blair – was a stricken figure when he commenced one of the defining novels of the 20th century, despite the literary celebrity he had lately attained through the success of Animal Farm (1945), his “fairy story” allegory of the Soviet Union.

Gaunt, in frail health and grieving the loss of his wife Eileen O’Shaughnessy, who had died suddenly and unexpectedly in March 1945 as a result of complications arising from a routine hysterectomy, Orwell’s friend and editor at The Observer, David Astor, suggested he take up residence on the remote Scottish island of Jura in the Inner Hebrides to get away from it all.

Astor knew the local laird, Robin Fletcher, who was in need of a tenant for his crumbling farmhouse, Barnhill.

Enthusiastic, Orwell set out with minimal luggage and furniture, with his sister Avril and a young novelist, Paul Potts, for company in May 1946, gladly leaving behind his role as book reviewer and correspondent at various newspapers and, more reluctantly, his adopted son Richard at home in Islington with a nanny, Susan Watson.

Barnhill turned out to be a four-bedroom cottage situated on the northern end of the island. It had no electricity, no access to a public telephone or post office, and the nearest hospital was on the mainland in Glasgow, a complicated journey at the best of times but especially perilous in rough weather. Orwell’s only connection to the wider world was his battery radio. His meals were cooked by Calor Gas and potent paraffin lamps lit his evenings.

Jura itself – still famed today for its whisky distillery – was home to only 300 people but its rugged beauty would prove an ideal change of environment for the writer.

After initially being forced to retreat to London to escape the particularly savage winter of 1946-47, Orwell returned with his young son and came to relish cultivating the garden, hunting rabbits in its wild armed with a shotgun, and fishing along the coastline for mackerel, pollock and lobster.

When he felt up to it, he would spend the majority of his days working on the novel he was then calling The Last Man in Europe in Barnhill’s sitting room, otherwise writing propped up in bed in a dressing grown, a roll-up cigarette packed with black shag tobacco clamped between his lips, a cold pot of coffee at his side.

Orwell had been meditating on his themes of dictatorship, the abuse of power and the possibilities of mass manipulation through language since the Spanish Civil War but said his ideas were really crystallised by the Tehran Conference of 1944, at which he saw Joseph Stalin, Winston Churchill and Franklin D Roosevelt carving up the world in anticipation of the defeat of Nazi Germany.

As he continued to chew over the plight of Winston Smith, Orwell suffered an accident that would ultimately kill him. Pootling along Jura’s coast in a motorboat during a bright summer day in August 1947, he and his party were almost drowned when their vessel fell afoul of the notorious Corryvreckan whirlpool.

Orwell was plunged into the icy waters but managed to swim to safety, though not without the shock doing lasting damage to his already weak lungs. Coughing alarmingly thereafter, to the consternation of his loved ones, he refrained from seeking help until he finally collapsed after completing the first draft of what would become Nineteen Eighty-Four on 7 November.

Shortly before Christmas, Orwell finally consented to be taken to the Hairmyres hospital in East Kilbride where he was diagnosed with chronic fibrotic tuberculosis in the upper part of both lungs. He was kept in care until July 1948 before returning to Jura to resume work through the following autumn.

Having made “a ghastly mess” of his original manuscript with corrections, Orwell painstakingly retyped his work at the rate of 4,000 words per day, seven days a week, according to biographer Dorian Lynskey, a force of effort that no doubt took too much out of him at a time when he was beset by fever and bloody coughing fits, gales blasting the cottage outside.

The novel was finished that December – Orwell drinking a glass of wine before retiring to bed, utterly exhausted – after which he decamped from Jura for the final time and took up residence in a sanatorium in Cranham, Gloucestershire, in early January 1949, a step he would have been well-advised to take much earlier.

“Everything is flourishing here except me,” he wrote to Astor. He was again kept apart from his son, this time for fear of infecting him.

Nineteen Eighty-Four arrived that summer to huge acclaim but Orwell himself would pass away the following January, though not before marrying Sonia Brownell – his inspiration for Julia in the book – from his sickbed at University College Hospital. Astor served as his best man.

Eric Arthur Blair, just 46, was laid to rest in All Saints’ churchyard in Sutton Courtenay, Oxfordshire.

His novel, of course, lives on as part of our political and social discourse, attaining a fresh new relevance in the “post-truth” 21st century, especially since the election of Donald Trump as US president.

“I think dad would’ve been amused by Donald Trump in an ironic sort of way,” Richard Blair told The Guardian in 2017. “He may have thought, ‘There goes the sort of man I wrote about all those years ago.’”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks