Alice in Wonderland: The making of a style icon

How come the first colour edition of 'Alice' had her wearing yellow, but she's now best known for her blue dress and black hairband? Kiera Vaclavik explains why the curious girl's look never stops changing

Gianni Versace compared himself to her, many of the world's most beautiful women have been photographed as her, and the great and the good of the fashion world have lined up to dress her. Alice in Wonderland may be 150 but her style seems to be eternal.

In 2003, Annie Leibovitz shot the American Vogue Christmas photo essay, for which the likes of Tom Ford, Karl Lagerfeld and Jean Paul Gaultier produced a new dress for Alice. There was just one stipulation: it had to be blue.

Fast-forward 10 years to another Christmas, and couture Alice had gone mainstream. In 2013, the cornerstone of the British high street, Marks & Spencer, unveiled an opulent feature film-esque TV ad, with Rosie Huntington-Whiteley as Alice entering an urban rabbit hole, shedding her surface world clothes as she hurtles down into wonderland (revealing more than a glimpse of RHW's lingerie range for M&S in the process), only to land smack in the middle of a tea party presided over by mad hatter male model, David Gandy.

M&S's simple blue "Alice" party dress quickly sold out (and was particularly popular with older ladies, judging by the online comments posted by shoppers). As one promotional Disney video of 2010 proclaimed in insistent and repeated upper case: ALICE IS THE NEW BLACK.

It was Carroll himself who first styled Alice, in the manuscript which he offered to his friend Alice Liddell as a Christmas gift in 1864. In these drawings, Alice undergoes a series of costume changes – probably as a result of Carroll's untrained draughtmanship: necklines constantly shift, sleeves shrink and grow, seams, tucks and collars appear and disappear. Such problems were ironed out when Sir John Tenniel, the illustrious Punch cartoonist, took over the reins for the first published edition of 1865. Still widely known today, these illustrations contributed enormously to the initial success of the text. Alice is shown consistently as a smartly but not too fussily dressed Victorian child. The pinafore which Tenniel adds – and is such an important part of our own conceptualisation of Alice today – suggests a certain readiness for action and lack of ceremony.

Modifications to Alice's appearance came quickly, and under the supervision of Carroll. By the time Through the Looking-Glass was published, just six years later, Alice has already been restyled. Her very full skirt becomes much narrower, flounces are added to her pinafore and a decorative feature is added to the waistband. It is only at this point that she gains the striped stockings and the hairband which takes her name.

Although they have received very little critical attention since, a whole raft of totally new visions of Alice were produced in the 19th century. Dutch, Danish and especially American editions offered their own Alices, which often departed dramatically from the Tenniel original: Alice with top knots, fringes and curls; Alice as a brunette and a redhead; Alice with long sleeves and stripes, elaborate ruff collars and cuffs; in a full-length orange dress with a black pinafore; or – frequently, Alice with no pinafore at all.

Some Victorian Alices were shown in a blue dress, but the first authorised colour edition of an Alice book saw her wearing yellow (with, blue trim to be sure), while pink and red were also common in many editions. A generally pale palette prevails in the 1907 editions. So in terms of colour scheme and general silhouette, Alice's image was, it's safe to say, yet to be fixed.

The process of dressing up as Alice, which began during Carroll's lifetime, tells much the same story. Professional and amateur performances of the Alice books took place across the world in the 19th century. Although reviews frequently mentioned the proximity between Tenniel's illustrations and the costumes, it's surprising the extent to which this doesn't apply to Alice herself, and how each production presents a new Alice look.

In the first professional production in 1886, for instance, Phoebe Carlo wore a high-necked, long-sleeved and fur-rimmed dress with no sign of a pinafore. Only the simple, single-strapped black shoes are recognisable to us as Alice-esque. Such differences between Alice on the page and on the stage did not go unremarked: one beady-eyed seven-year-old wrote disparagingly of the lack of pockets in Ellaline Terriss' costume in a 1900 production.

Disney's 1951 Alice marks a triumphant return to Tenniel. The full skirted, neat waisted Victorian silhouette was easily absorbed into, and very much in tune with, the post-war "New Look" styles. This Alice, based on drawings by Mary Blair, must be the single most influential post-Tenniel rendering of Alice, if not of all time. It's the one which has done the most to fix her image, to wed her firmly to a blue dress and white pinafore, to blonde hair and black shoes.

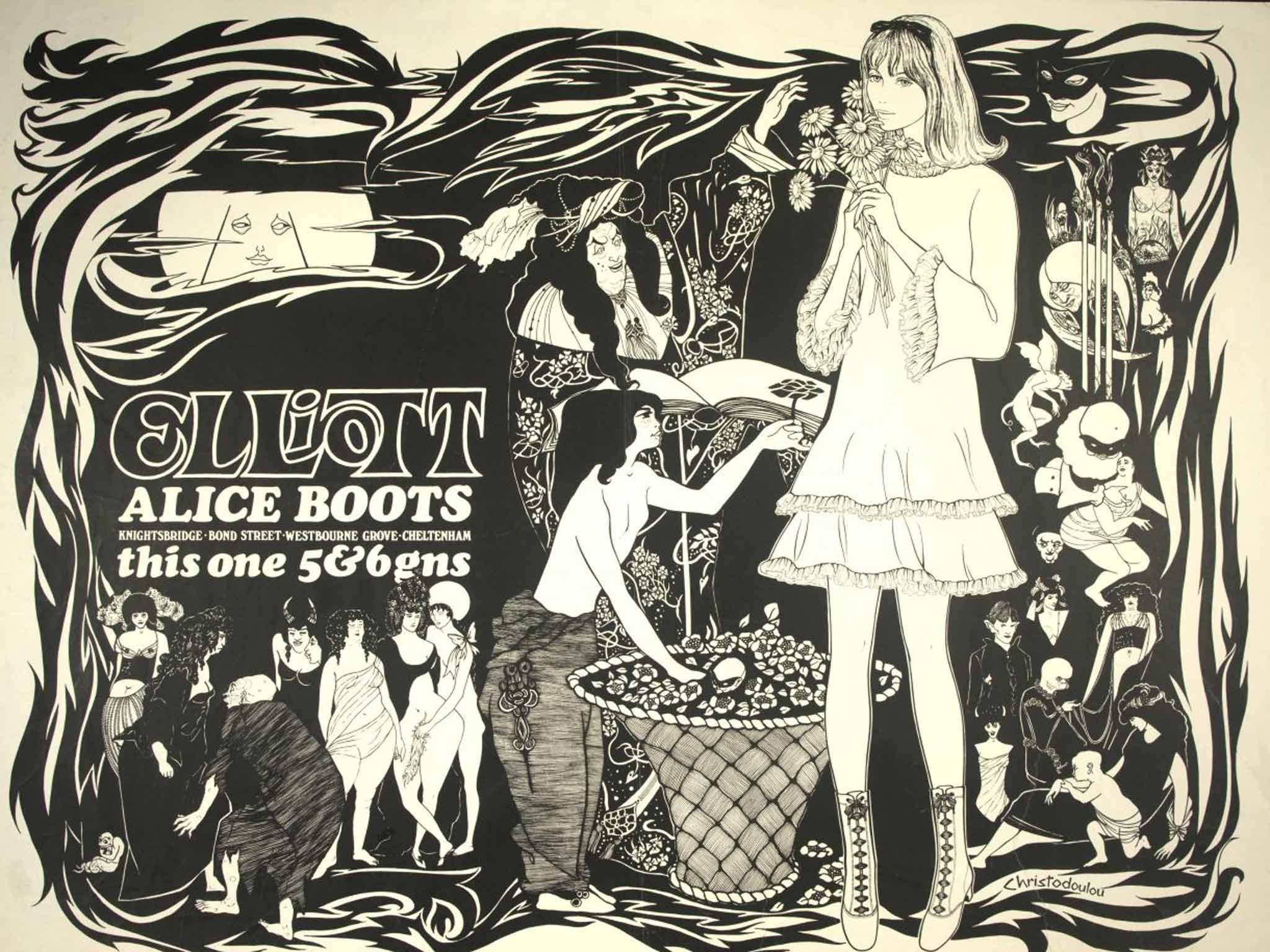

The Wonderlands of stage and screen have in fact always been a driving force in Alice's development as a style icon. It was the 1933 Paramount film version which seems to have prompted the adoption of the Alice band as hair accessory of choice at hunt balls and wedding processions across Britain. Seeing walking, talking Alices fired imaginations – not least those of merchandisers. The flurry of tie-in jewellery and make-up sets, produced around the release of Burton's 2010 version for Disney, is only the latest iteration of a well-established process.

But the huge upsurge in Alice's style credentials over the last 20 years isn't just about film tie-ins. A GQ feature of December 2000 pre-dates both Burton's film and Leibovitz's shoot for Vogue. In it, Alice is a 16-year-old Lizzy Jagger sporting a sheer cream blouse and red diamante hairband, accompanied by older sister Jade as the Cheshire Cat up a tree in bra and boots, Kate Moss as the white rabbit and various other "high-profile fun-lovers" of the "Cool Britannia" scene. It's all about quirkiness and anarchy, behaviour which "quickly degenerates", and turns a tea party into a Moët-fuelled food fight.

Alice is indeed part of a broader Wonderland aesthetic which can be by turns sweet and cloying or much darker – more sex, drugs and rock and roll – or both combined. And this is what makes it difficult to give a definitive answer to the question of why so many people, in so many walks of life, are dressing like Alice or wearing the clothes which she adorns.

Alice has, then, become something of a blank canvas, able to absorb a huge range and combination of emphases and directions. Although a much more fixed sense of her image has emerged than in the 19th century, she continues to multiply in a constant stream of new editions and interpretations. And each time a celebrity dresses as Alice or an artist or designer reinterprets or alludes to her, her cultural capital – her sheer allure – keeps on growing. Will Alice retain her position as a style icon in another 150 years? Curiouser things have happened.

'The Alice Look' opens at the V&A Museum of Childhood, in Bethnal Green, east London, on 2 May.

Dr Kiera Vaclavik is a senior lecturer at Queen Mary University of London

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks