Bad sex please, we're British: Can fictive sex ever have artistic merit?

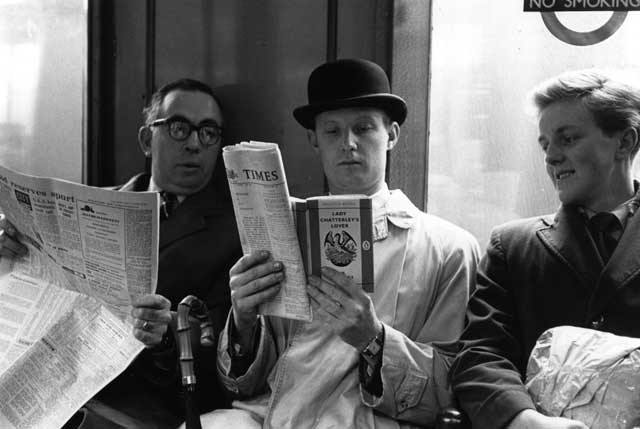

When the unexpurgated Penguin edition of Lady Chatterley's Lover was finally cleared of obscenity, three decades after DH Lawrence's death and a highly-publicised trial, it marked a victory for literary freedom. Those who had not already got their hands on a contraband copy rushed to exercise their right to read of Lady Constance and her gamekeeper lover, in flagrante, uttering previously unprintable words.

Readers were not the only ones forming a hasty queue. In the decades following November 1960, writers exulted in their new-found Lawrentian rights to express their erotic imaginations before critics began questioning the artistic merits of this modern-day deluge of explicit sex in literary fiction.

By the early 1990s, a peculiarly British form of disapproval had grown out of the notion that sex and serious literature made for uncomfortable bedfellows. The priapic imaginings of otherwise revered writers – Philip Roth, John Updike, Amos Oz, John Banville – were selected and sneered at for inducing the wrong type of grunts and groans, in the annual tradition that has become The Literary Review's Bad Sex Awards.

The most purple of this year's blue passages is once again to be put in the stocks by the magazine at their awards ceremony later this month.

While these nominations provide testimony to the creative potholes authors can slip down when they stray into the bedroom, the awards themselves prove their opposite – good sex writing - does exist. Against that the bad is selected, according to Jonathan Beckman, assistant editor of The Literary Review.

But for all the vituperation at authors who get it wrong, there appears to be little consensus on how to get it right. Some writers follow the forensic language of anatomy, others adopt metaphor and euphemism, while opponents of literary sex shun it for crass approximations with pornography.

Ironically, the bad sex awards were originally conceived, in 1993, to celebrate good sex, before the editor, Auberon Waugh, was advised by co-founder, Rhoda Koenig, that this might be "less interesting" than plucking out the clichéd and the corny. Waugh went with her suggestion. "For something like 15 years I had to review a novel a week in various publications," he explained in an article for The Erotic Review, "and bit by bit I noticed how practically every novelist had taken to including a sex scene which had nothing to do with the plot and added nothing to the enjoyment of the narrative. Nobody could possibly have been aroused by these awkward, perfunctory couplings."

These days, the prize is viewed either as a dated literary joke, or more seriously, as a deterrent. Andrew Motion bemoaned the dearth of sex in this year's Man Booker prize long-list during his tenure as its chair, and raised the annual debate over whether the prize had not discouraged writers from unleashing their erotic imaginations on the page. This suggestion may go too far in assuming the awards' influence over the minds of novelists, but perhaps their continued existence serve to keep fresh the fear that any description of sex might veer perilously close to erotica, with its cheapening effect of sexual arousal. That was most recently expressed by Martin Amis, who spoke of the impossibility of writing sex in fiction without descent into pornography.

John Freeman, the editor of Granta magazine who oversaw a special edition dedicated to sex earlier this year, says that although contemporary fiction abounds with eloquent discussions "around" and "about" sex, there is a level of apprehension among some writers who find themselves searching for a fitting vocabulary to describe its actual mechanics.

"The feeling that sex isn't fully represented in literature proves to be a false one if you expand just beyond the actual act, to all the things that sex encompasses. But once you get down to writing the act, it's very hard to do it without sounding like bad erotica or embarrassing self-disclosure. I remember Adam Foulds saying at our event: 'You can almost see many male writers' brain chemistry change as they write certain scenes and their ability to judge what is good writing get away from them'."

Mitzi Szereto, an author and teacher of erotic writing workshops, says writers on her courses are held back when they seek refuge in their own sexual histories: "You wouldn't rely on personal experience for any other kind of fiction writing so why would you when crafting a sex scene? I encourage people to write beyond their own sexual encounters, and when they do, they are less inhibited and more creative."

Szereto thinks the best kind of sex writing needs to explore the "psychology of desire". In an age in which sex has been divested of most of its mystery (hard-core pornography is a website away and Mills & Boon has invested in a "raunchy" series), it may be that the "psychology of desire" is the only unknown territory to explore.

Howard Jacobson, who last month won the Man Booker prize for The Finkler Question, believes it is the discussion of sex that is the intriguing part, not its depiction. "The only point in writing a 'he puts that in there and she puts this in here' scene is to arouse, and I'm not interested in doing that. Some critics who should have known better complained that my last novel, The Act of Love, didn't arouse them. It wasn't meant to. It was a book 'about' compulsive jealousy. It wasn't intended to make them jealous or otherwise titillate them.

"To a novelist - to me, anyway - the 'about' is more interesting than the thing. Explicitness almost invariably takes you to bathos. The great sex scenes in literature for me don't show sex at all – Dorothea in Middlemarch, for example, registering the sexual horror of her marriage through her revulsion from Roman art... It isn't morality that determines this preference in me, but aesthetics."

Geoff Dyer's artistic judgement does not stop him at the bedroom door. The superannuated omission of sex in stories that deal with themes of love, passion and romance is as artificial as a black-and-white film featuring a Bogart-Bacall kiss which segues into the next, unrelated scene, he argues. He has sought to keep the film rolling.

"In 1989, I published my novel, The Colour of Memory. It had a lively romance in it and the climactic moment was this kiss. It was rather a nice kiss but I had a sense then that it was like a throwback to early film convention whereby the scene afterwards goes blank and everything else is implied. I wanted to depict a completely lively, non-weird relationship which included full-on sex.

"Once the decision had been made, that a relationship would be consummated between two people, then it seemed to me right in the modern age to follow them into the bedroom. It was in reading Allan Hollinghurst's books where you get, without any change of gear at all, this shift from beautiful, classical British prose to the words 'his cock was in my mouth' that I wondered whether it was possible to come up with a heterosexual equivalent."

The literary challenge in writing three detailed sex scenes for his latest novel, Jeff in Venice, Death in Varanasi, were immense, he admits, because "you are faced with a limited number of verbs and nouns". Yet the act of sex can be convincingly rendered, if done straightforwardly.

"It seems to me if you do write it, it has to be absolutely explicit – no metaphors, no hyperbole. After writing Jeff in Venice, Death in Varanasi, I said to my editor, 'I will bet you any sum of money I won't be listed for the Bad Sex awards'. Descriptions of throbbing orbs lends themselves to the awards, not [a sentence like] 'he stuck his tongue in her arse'."

Beckman agrees with Dyer that it is "less ostentatious" sex that is the most effective. "The best sex scenes are the ones that are quite clinical and precise. Colm Tóibín's short stories are quite good, there is a good sex scene in Bret Easton Ellis's Imperial Bedrooms; Dyer wrote perfectly reasonable scenes in Jeff in Venice, Death in Varanasi. He just tells you what happens; what's not good is the over-florid writing that imbues sex with transcendental meaning."

Philip Kerr, novelist and recipient of the Bad Sex Award in 1995 for Gridiron, is wary of conclusive theories on judging the good from bad. The passages deemed bad are sometimes the most original because description is "off the beaten track".

For Gridiron, he employed the gentle language of metaphor, and felt he was perhaps punished for it. "I think I won the award for one word – gnomon – which is the hard part of a sundial. When you are writing about [sex] and the penis, you are looking for comparisons, and I made this one given the transient nature of both time and an erection."

Kerr has not stopped writing explicit scenes in subsequent works, to reveal character and motivation. "I've just published my latest novel, Field Gray, and it's got one sex scene in it which has an old man having sex with a younger woman in Cuba. She's scared of being picked up by the Cuban police and she wants someone to cuddle her. He doesn't think this event has got anything to do with him being a sexy man - he is her protector so the scene is revealing that relationship between them."

Koenig casts doubt over this rationale: "I do think writers should ask themselves 'is this sex scene necessary?' In other words, what will we learn from following the people into the bedroom that we will not learn from simply being told that they have gone to bed together and liked it or disliked it or felt guilty about it or whatever?"

Do we even need these graphic interludes in an era which has made sex and its availability in all forms not only permissive, but pedestrian? asks Koenig. Modern literary battles are no fought by publishers over sex, as they were by Penguin in 1960. One wonders whether DH Lawrence would see sex, such a disposable currency today, as the same potent gift to literary fiction. The most interesting writing about sex in the past two decades has arguably come from gay and lesbian novelists – Hollinghurst, Jeanette Winterson, Edmund White - who have touched ground where there has still been sensibilities to disturb and imaginative barriers to break down.

"Nobody needs it anymore", says Koenig. "Not that long ago, people would read quality fiction (as well as, of course, lots of rubbish) to discover what actually went on during sex, how people did it. Virgins wanted information, and experienced people wanted inspiration. If you were too young or poor to buy pornography or instruction books and had to go to the library, it was a lot less embarrassing checking out Lady Chatterley than a sex manual."

In her introduction to the Penguin's 2004 edition of Lady Chatterley's Lover, Doris Lessing pokes gentle fun at the timidity of the sex scenes that caused such moral approbation in pre-1960s Britain. To us now, the book is not nearly as "explicit" as it once was, with its opaque descriptions of anal sex and pulpy scenes of Constance and Mellors weaving flowers in each others' pubic hair. But how it is still useful is in serving as "a report on the sex war of his [Lawrence's] time."

Yesterday's sex might be today's schmaltz, but Lessing appears to present a simple yet convincing argument in its favour. What such scenes capture so vividly is a kind of social history of the bedroom that deserves a rightful place in literary fiction. "The description of what happens in the bedroom, between the sexes with all the power-play between the genders is a vital and valid documentation in literature," she says. Bad sex, for this purpose, could be just as enlightening as good.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments