The 20 best books of 2020, from Strange Flowers to Shuggie Bain

In what has been a grim year for us all, Martin Chilton highlights the publications in which escapism and the joys of imagination have been sustaining and enriching

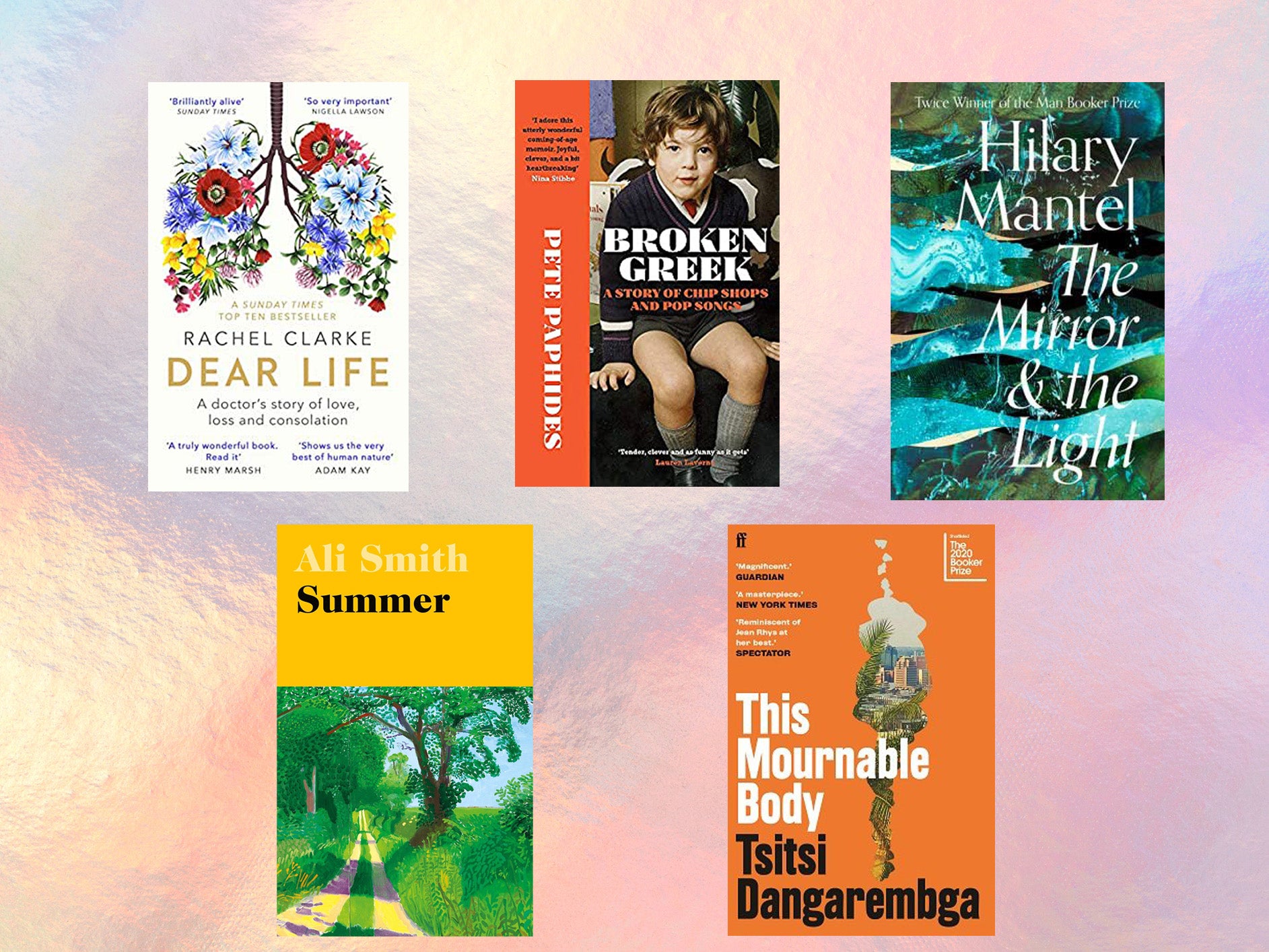

Whittling down the best reads of 2020 was tough – particularly as it necessitated leaving out wonderful novels from Isabelle Allende, Maaza Mengiste, Matt Haig, Andrew O’Hagan, Jenny Offill and Sigrid Nunez; dazzling debuts from Avni Doshi, Brandon Taylor, Molly Aitken, Louise Hare, Naoise Dolan and Paul Mendez; outstanding history books from Francesca Wade, Michael Taylor and Michael Wood; and marvellous memoirs from Deborah Orr, Richard Holloway and Michele Roberts.

I plumped for the books that have meant the most to me in what has been a grim year for us all, publications in which escapism and the joys of imagination have been sustaining and enriching. I leaned heavily towards fiction, although the selection also features the nature, history and biographical books that have touched me most in the past 12 months.

These are the 20 best books of the year.

20. That Old Country Music by Kevin Barry (Canongate)

There have been some cracking short-story collections this year, including those from poet Frances Leviston, Thai-born Souvankham Thammavongsa, Nicole Krauss and John Lanchester. My favourite was Kevin Barry’s That Old Country Music, which is full of memorably offbeat stories and bizarre characters. “She had a face on her like a scorched budgie,” is how Barry describes the heroine of the title story, a girl pregnant by her mother’s feckless boyfriend. His collection is an original, insightful window into modern Ireland.

19. Rootbound: Rewilding a Life by Alice Vincent (Canongate)

I’m sure many of us have sought solace and healing from the wonders of the living world during the anxious months of lockdown. This past year has been a golden one for nature writing, with fabulous books from David Attenborough, James Canton, Stephen Moss and Lucy Jones. The most affecting book for me, though, was Rootbound: Rewilding a Life in which Alice Vincent, a champion of urban gardening who founded Noughticulture, delivered a poignant testimony to the joy and hope greenery brings to your life.

18. Utopia Avenue by David Mitchell (Hodder & Stoughton)

For those who have felt the pain of missing live concerts as a result of the pandemic, David Mitchell’s novel Utopia Avenue was a hugely enjoyable reminder of the sheer thrill of music. His ambitious tale of a band’s rise to fame in 1967 captures the ego clashes, groupies, rip-off promoters and record-company parasites who are part and parcel of a wild business. There is fun, too, with real-life musicians seeded throughout a fable-like story that is full of perceptive descriptions of musicians.

17. The Devil and the Dark Water by Stuart Turton (Raven Books)

Over 550 pages, Stuart Turton’s The Devil and the Dark Water overflows with wonderful characterisations, neat similes and enough horror, mystery and crime to keep anyone enthralled. In Turton’s thriller, set on The Saardam ship in 1634, the sexism of 17th-century society is one of the deeper, darker themes explored in a historical novel that is also a story of wealth disparity, avarice and how power corrupts. It’s a rollicking escapist read.

16. Mr Wilder & Me by Jonathan Coe (Viking)

With all the cinema closures, I watched a lot of classic films on the small screen this year, including Billy Wilder classics such as The Lost Weekend, The Apartment and Some Like it Hot. In Jonathan Coe’s Mr Wilder & Me, we meet the Oscar-winning movie director in the twilight of his career, when he gives a job to a young Greek girl called Calista Frangopoulou. At the heart of this enchanting book’s success is how Coe brings Wilder gloriously to life, capturing both his lingering, implacable melancholy and his caustic wit and charm.

15. The Actress by Anne Enright (Jonathan Cape)

Anne Enright’s The Actress is a beautiful, psychologically masterful novel about a complex mother-daughter relationship. The mother is Hollywood star Katherine O’Dell; the daughter is a marginally successful author called Norah, who is trying to make sense of the “merry-go-round” upbringing she survived. Katherine’s back-story is told with humour and deceptively simple insights. Their shared history of facing manipulative, predatory men is achingly sad, and all too illuminating of our present age. The Actress is funny, perceptive and sorrowful.

14. The Weekend by Charlotte Wood (Weidenfeld & Nicolson)

Old female characters don’t often get to occupy centre stage in modern fiction, but Australian author Charlotte Wood’s three 70-something protagonists in The Weekend are exquisitely drawn. All sorts of emotions and humorous situations erupt when the trio (and a dog) reunite for a weekend in New South Wales to clear out the decaying beach house of their recently dead friend Sylvie. As well as being a shrewd dissection of grief, regret and the realities of bodily decay, The Weekend triumphantly brings to life the honest, inner lives of three interesting women.

13. This Mournable Body by Tsitsi Dangarembga (Faber)

Tyrannical leaders have been a feature of 2020, a year in which Tsitsi Dangarembga was targeted because of her public dissent. Dangarembga’s This Mournable Body is the third instalment in a trilogy following the protagonist Tambuzai’s life in Zimbabwe. This profound tale of being dashed down by life in a decaying post-colonial state earned the book a place on the Booker shortlist. It is narrated in a distanced second-person and although it is a deeply personal tale, it also casts a cold (and comical) eye on the wider impact of racism and sexism on a 40-year-old woman in Zimbabwe.

12. Snow by John Banville (Faber)

There were stacks of good crime thrillers this year – including books by Ian Rankin and Sabine Durrant and the deserved best-seller hit for Richard Osman and his entertaining caper The Thursday Murder Club – but my favourite was John Banville’s Snow, a murder mystery set in an Irish country house in 1957. It’s full of immaculate, stylish prose, and the crime is a starting point for a deft, penetrating study of the elaborate rituals of class and religion in post-war Ireland.

11. Strange Flowers by Donal Ryan (Doubleday)

It was a particularly good year for Irish literature, and Strange Flowers, partly set in the 1970s and about a girl who mysteriously flees her life on a farm, is a sensitive novel about the joys and vindictiveness of small-town rural life and the tumultuous emotions of family groups. Donal Ryan, twice Booker-longlisted, has deservedly established a reputation as one of Ireland’s most important novelists. Strange Flowers is a triumph. I was entranced by the way Ryan slowly and beautifully reveals the way that even broken people can open the door fully to the truth of themselves.

10. The Vanishing Half by Brit Bennett (Dialogue)

Brit Bennett’s mesmerising gem about the Vignes twins, who disappear from a Louisiana farm town on a hot summer’s day in 1954, is a masterclass of moving storytelling. The Vanishing Half, which was shortlisted for Waterstones Book of the Year, is a thought-provoking assessment of race and social politics in post-war America. The powerful plot twists in the novel, which concludes in 1986, will keep you gripped until the end.

9. Summer by Ali Smith (Hamish Hamilton)

Ali Smith completed her ambitious seasonal quartet with the sublime Summer, which was started and completed during this gloomy year. Summer takes in the fractious events of Brexit, the global virus and the needless care home deaths, and the Black Lives Matter protests that followed the killing of George Floyd. The novel offers wisdom, humour and the hope of better days to come, including the uncomplicated joy of a beautiful summer afternoon in the English countryside.

8. The Mirror & the Light by Hilary Mantel (4th Estate)

Expectations were justifiably sky-high for the final instalment in Hilary Mantel’s portrait of Thomas Cromwell – which started with Wolf Hall (2009) and continued with Bring Up the Bodies (2012) – and although there was no third Booker award, Mantel’s concluding novel was another jewel of historical fiction. Her depiction of royal court intrigue is superb and full of relevance for our own craven times. The Mirror & the Light offered another illuminating portrait of Cromwell, and is also a complex, insightful exploration of power, sex, loyalty, friendship, religion, class and statecraft.

7. The Lost Pianos of Siberia by Sophy Roberts (Doubleday)

The scope of history books was so immense this year that it was hard to pick a standout selection from a crop that included Matthew Cobb’s The Idea of the Brain: A History and The Hidden History of Burma by Thant Myint-U. The one that gripped me the most, however, was The Lost Pianos of Siberia by Sophy Roberts, which is a stunning example of modern historical travel writing. The intrepid Roberts finds a brilliant way to summon a complex picture of Siberia through the story of how music found its way to one of the most remote places on earth.

6. Interior Chinatown by Charles Yu (Europa Editions)

In November, Charles Yu won the National Book Award for Fiction for Interior Chinatown, a satire about typecasting and racism in Hollywood. This inventive experimental novel, narrated in the second person and written in the form of a screenplay, captures the weirdness of existence and is by turns a hilarious expose of modern prejudice and a heartbreaking existential portrait of Asian American identity. It was like nothing else I read in 2020.

5. Broken Greek by Pete Paphides (Quercus)

Memoirs are tricky things to get right, and the best balance honesty with humour, acute self-analysis with perspective. I enjoyed autobiographical books by Deborah Orr, Ayad Akhtar, Hadley Freeman and Nicholas Royle, but the most enjoyable memoir for me was Broken Greek by Pete Paphides. It captures why the 1970s was such a weird decade and is also a loving testimony to the part music played in helping Paphides find a cultural identity. The book is also full of witty, authentic reflections on football, something you don’t always find when authors horn in on the beautiful game.

4. Apeirogon by Colum McCann (Bloomsbury)

Colum McCann’s transcendent book Apeirogon is fact-based fiction, telling the story of the unlikely friendship between Israeli Rami Elhanan and Palestinian Bassam Aramin, both of whom lost daughters to violence. McCann stitches together reflections on history, the nature of friendship, politics, the conflicting power of hatred and forgiveness, wildlife and art – turning them into a gorgeous tapestry. Booker-longlisted Apeirogon is about death and destruction, yet pain is part of what makes this book an essential hymn to peace and forgiveness.

3. Hamnet by Maggie O’Farrell (Tinder Press)

Hamnet is set in an England devastated by a plague that kills the young son of William Shakespeare. Maggie O’Farrell deservedly won the 2020 Women’s Prize for Fiction for her profound, moving story of the boy’s death and the part this family disaster played in inspiring Shakespeare’s famous tragedy Hamlet. The ending to the novel is entrancing and O’Farrell’s meditation on the human experience is a triumph of imagination.

2: Shuggie Bain by Douglas Stuart (Picador)

Although Shuggie Bain is a gloomy, brutal read, there is an underlying compassion and humour that make it an enriching one. It is also, at heart, a tender love story about a gay boy called Shuggie and his troubled alcohol-addicted mother Agnes. Douglas Stuart was the unanimous winner of the Booker Prize and his novel stood out by offering something so personal, so deeply seen and so overflowing with emotion. Glasgow, the setting for a story that takes place in the recession-hit 1980s, is its own glorious, anarchic character in the book. This is a modern masterpiece of humane storytelling.

1. Dear Life: A Doctor’s Story of Love and Loss by Rachel Clarke (Little, Brown)

Bereavement and misery have been a constant in this troubled year of coronavirus death charts. Although it may sound strange, I found it helpful to read profoundly thought-provoking books about mortality, such as David Jarrett’s Meditations on Death: Notes from the Wrong End of Medicine. The book that bowled me over, however, was Dear Life by palliative care doctor Rachel Clarke. Although it is a painful read, because it forces you to reflect on some of the worst situations anybody ever has to face, the book is also a compassionate, wise gem, full of its own moments of sweetness. Clarke powerfully conveys the battering the NHS has endured over the past decade of austerity and false government promises, and her book should be essential reading for anyone who cares about our beleaguered health system. Dear Life was simply the most inspiring book I read in 2020.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks