Best economics books 2015: High time for an authoritative history of finance

From John Kay's Other People's Money to Barry Eichengreen's Hall of Mirrors

Oceans of ink have been spilled and great forests felled in recent years to produce books on the global financial crisis. We've had instant histories by journalists, polemics from activists, self-justifying memoirs from regulators, blueprints for reform from academics. But only this year, it seems, have we finally started to get books that grapple with the most important question: What is finance actually for?

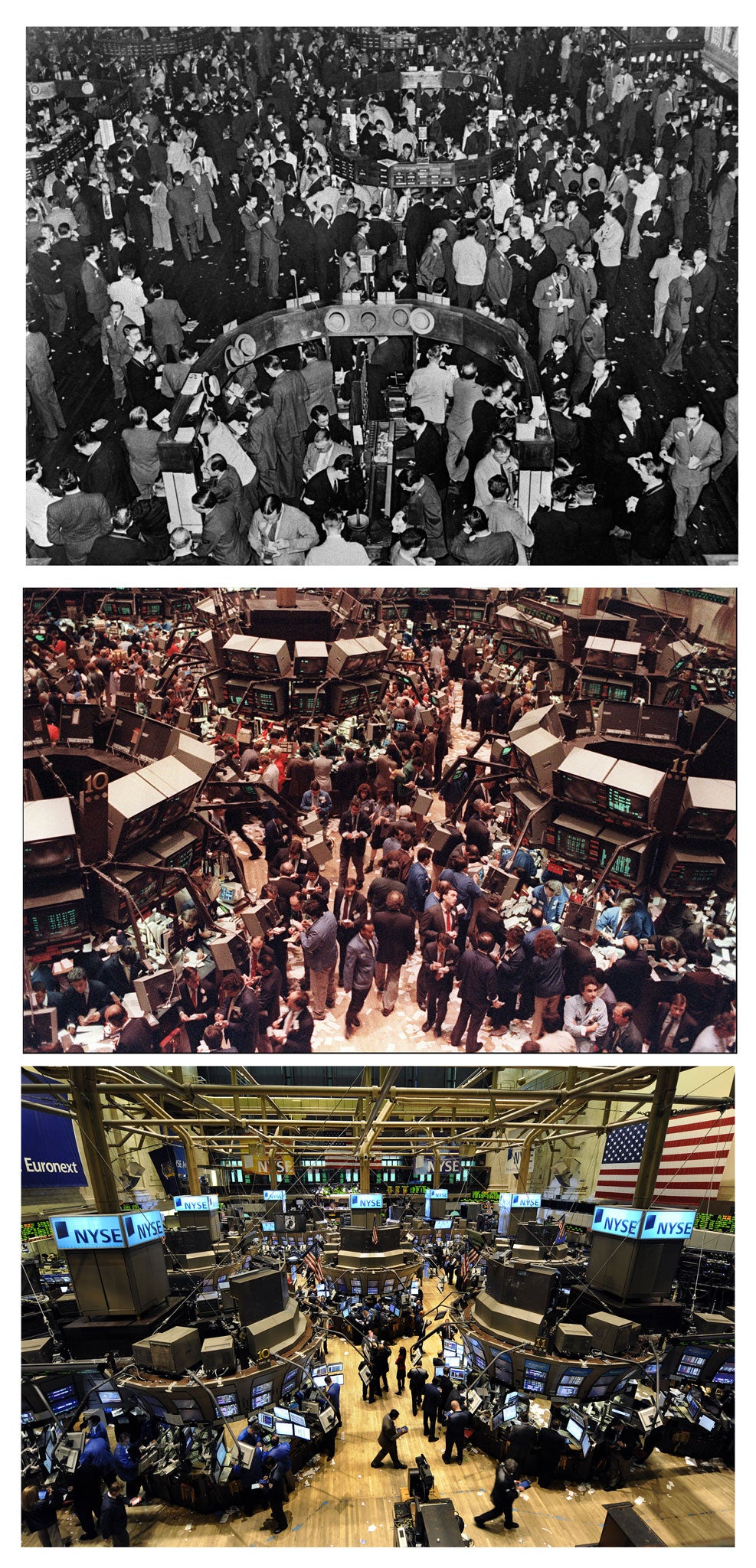

That's the question that John Kay keeps at the heart of his Other People's Money (Profile, £16.99). In this beautifully written and stratospherically authoritative work, Kay makes it clear that most of what Wall Street and the City of London do is irrelevant to the needs of the non-financial economy. Large banks don't, by and large, provide finance capital to companies in the way that we naively imagine. Nor do they help us manage risk in any meaningful way. Most of their activity (and the area where the attention of their managers is focused) is on socially useless trading among themselves.

Kay's solution is radical structural reform of finance in order to turn the masters of the universe into servants of the people once again. A complement to Kay's books is Adair Turner's Between Debt and the Devil (Princeton, £19.95). It was Turner, a former chairman of the Financial Services Authority regulator, who coined the phrase "socially useless" back in 2009 to describe many of the complex modern activities of financiers. It was a description that offended the financial lobby at the time. But, as Kay's work shows, Turner was bang on the money. Turner's book covers some of the same ground as Kay but it also develops a novel economic thesis, arguing modern financial sectors have an inherent and uncontrollable tendency to create excessive levels of debt.

Neither Kay nor Turner have much time for the doctrine that markets are always and everywhere "efficient". Nor do George Akerlof and Robert Shiller. In Phishing for Phools (Princeton, £16.95), the two Nobel laureates illustrate in a wonderfully accessible way how free markets – far from always being the ordinary person's friend – can create a happy hunting ground for predators. They explain how these predatory tendencies are not merely unusual quirks to be factored into economic models as add-ons – but ought to be at their very heart.

Speaking of economic models, Dani Rodrik, in Economic Rules (OUP, £16.99), provides an edifying discussion of these basic tools of the economist's trade. Some argue the use of models, with their simplified assumptions of the way people interact in markets, makes economics a pseudo-science. But Rodrik argues, compellingly, that the problem is not in models themselves but their misuse by some ideologically motivated or clumsy practitioners. They key is finding the right model for the right occasion.

Barry Eichengreen is one of the pre-eminent historians of the Great Depression. The trauma of recent years in the global economy has borne striking similarities to that earlier catastrophe. And that has helped make Eichengreen one of the most clear-sighted of commentators in recent years. He brings all his insights together in Hall of Mirrors (OUP, £20).

He argues that while, this time around, policymakers did take enough action to prevent total financial disintegration, the lack of another Great Depression is precisely what killed the chances of proper financial reform. "Success thus became the mother of failure" is Eichengreen's bitter-sweet and all too plausible conclusion.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks