Boyd Tonkin: The Nobel plot against America?

The week in books

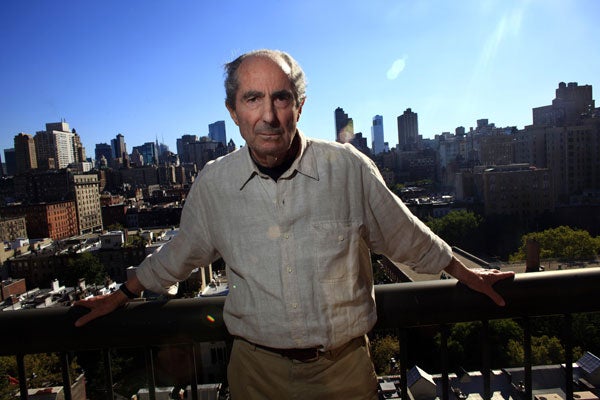

When the biennial Man Booker International Prize came into being, cynics muttered that, at last, here was a Booker gong that Philip Roth could win and so satisfy the transatlantic tastes of the sponsoring hedge-fund. Rather impressively, in 2005 the inaugural trio of judges for this lifetime-achievement honour silenced the doubters by selecting not an American but an Albanian: that wily master of the political fable, Ismail Kadare. Since then, Chinua Achebe and Alice Munro – estimable chocies both – have taken the prize. But on Wednesday, at the Sydney Opera House, it was announced that this time Roth has indeed prevailed. The 78-year-old novelist emerged from his Connecticut seclusion not just to thank old admirers but to seek new ones, voicing the hope that "the prize will bring me to the attention of readers around the world who are not familiar with my work".

Does Man Booker recognition make it more, or less, likely that Roth will finally snare the Nobel Prize that has eluded him for so long? Hard to call – as with anything connected to the capricious Swedish Academy. A while ago, I took part in a panel discussion with the Academy's then permanent secretary, Horace Engdahl. Everyone wanted to know if Roth somehow suffered from a standing Nobel veto, as Graham Greene apparently did. Not at all, Engdahl maintained: there was no barrier in place to his eventual success. Yet in 2008, Engdahl bowed out with a notorious interview in which he scorned the alleged parochialism of US authors and blamed them for not participating in "the big dialogue of literature... That ignorance is restraining."

Oh dear. Euro-myopia can sound just as dumb and vexing as the Anglophone variety. Not that the author, within the past 15 years alone, of American Pastoral, I Married a Communist, The Human Stain, The Plot Against America, Everyman and Nemesis needs to bother about the prejudice of Swedes. What's interesting, if still depressing, here is the limpet persistence of morbid fantasies about the "other" that you find in "European" or "Anglo-Saxon" descriptions of the culture on the far side of the fence. I deploy the scare-quotes because I have never for a second seen how any halfway-intelligent human being could believe in those abstractions. Yet as the Dominique Strauss-Kahn affair proves in a much more tragic vein, such spectres can sway events.

Roth's plea this week for a new international constituency that he might touch "despite all the heartaches of translation" sounds to me like a coded bid for support beyond the entrenched anti-Americanism of some global opinion-formers. With luck, this latest celebration will encourage new ways of reading him as well.

There's a deeply ironic side to the alleged incompatibility of his fiction with some non-Anglophone ideal of literary excellence. In effect, Roth in the first decade of the 21st century became a more purely "European" writer that ever before – even though the creator of The Prague Orgy and the other "Zuckerman" fictions had never needed lessons in narrative self-consciousness done to a Mitteleuropäische recipe.

Everyman, Indignation, The Humbling and Nemesis count as "short novels" for Roth, in sensibility as much as bulk. They demand to be read in the light of the bleakly compressed and clutter-free aesthetic of terminal wisdom that Edward Said, in his classic study of the subject, called Late Style. If you look around for antecedents and counterparts to the remorselessly introspective and linguistically austere minimalism of senior Roth, they exist more prominently outside the English language than within it. File him not with Bellow, Updike and Mailer any more, but with Bernhard, Handke and Beckett.

Whether in expansive or niggardly mood as narrator, Roth counts as a genuinely global talent and so merits this award. However, it worries me that the Man Booker International has gone to English-language authors three times in succession. In this round, the final field of 13 authors included just five who write in other languages. Among them was the extraordinary Spanish iconoclast Juan Goytisolo, who has kept his special flame of adventurous integrity in literature and life alight for almost 60 productive years – right up to his refusal, in 2009, to accept a Gaddafi-funded prize in Libya. Maybe he should take the Nobel now.

The world comes to Bloomsbury

Taking place both at its gloriously nutritious store and in the British Museum, the London Review Bookshop's "World Literature Weekend" returns on 17-19 June. Illustrious vistors include Cees Nooteboom (in conversation with AS Byatt), Javier Cercas, Manuel Rivas and Daniel Kehlmann; and Najat El Hachmi (right) will join fellow-Catalans Teresa Solana and Carles Casajuana. In a literary version of extreme sports, a "live translation" event will see Kehlmann setting the challenge of a new text to Shaun Whiteside and Mike Mitchell. I will join other judges to discuss the Independent Foreign Fiction Prize. Full details and bookings at www.lrbshop.co.uk/wlw2011

Applause for the law of freedom

How piquant that a leading judge should win the books division of the George Orwell Prize, named for a former colonial policeman who in "Shooting an Elephant" imperishably showed the shoddy masquerade that law becomes when it has no true legitimacy. Posthumously, Tom Bingham – Master of the Rolls, Lord Chief Justice and Senior Law Lord, who died in September – took the prize for The Rule of Law (Penguin). With masterly lucidity, his book ties the authority of justice to its practice and protection of universal rights. Bingham's law is the safeguard of liberty and dignity for all, not their cage. In the spirit of the book, Lady Bingham accepted the award with a defence of the Human Rights Act - one of her late husband's great causes – against its lazy denigrators. Which of its rights would the sniping critics prefer not to enjoy, she asked. The right not be tortured? Not to be enslaved? To freedom of speech? To a fair trial? Orwell, no worshipper of wigs and robes, would have cheered.

b.tonkin@independent.co.uk

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks