Boyd Tonkin: Why do autocrats love authorship?

The week in books

If you admire tender rustic realism in the verse of Thomas Hardy or Edward Thomas, you might enjoy an 1890s poem about "our friend Nininka", once a sturdy countryman who "walked straight on the stubble field/ Wiping the sweat from his face". Now, "His strong shoulders have drooped", as "the old man lay crippled/ Telling stories to his children". Or, if the classical poetry of China appeals, you may relish the painterly grace of "Snow", with its "North country scene:/ A hundred leagues locked in ice,/ A thousand leagues of whirling snow./ Both sides of the Great Wall... The mountains dance like silver snakes/ And the highlands charge like wax-hued elephants/ Vying with heaven in stature."

Between them, the authors of those poems caused the deaths of perhaps 50 million souls. Under his early pseudonym "Soselo", the young Georgian intellectual Josef Dzhugashvili published poetry in the literary reviews of Tbilisi. The man who became "Stalin" forsook his muse soon afterwards; but Mao Zedong went on penning finely-wrought poems through guerrilla warfare and the Long March. Young Stalin could, at his strongest, count as a passable bucolic lyricist. Mao, while no innovator, did much better than that. The same mind can engage in mass-murdering tyranny and a lively interest in literature and other forms of art. And the butchers of the future may show creative promise, or even genuine talent.

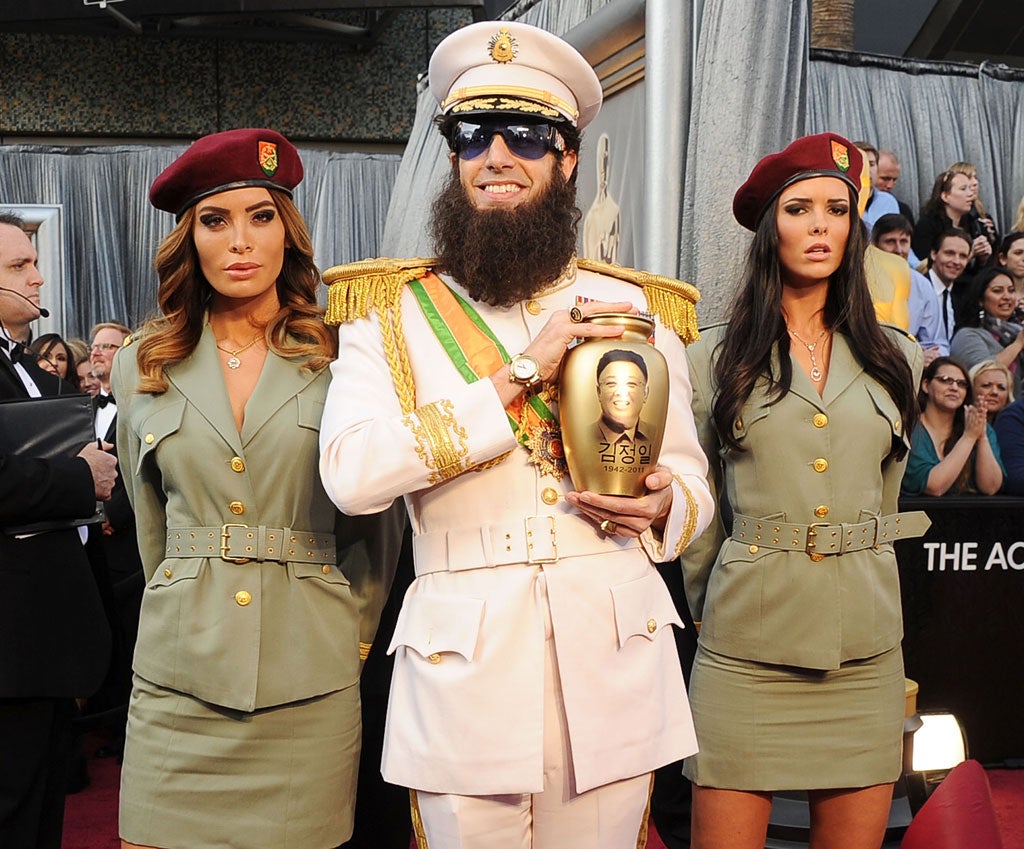

Sacha Baron Cohen, the Great Embarrassment himself, pulled the red carpet from under Hollywood's feet at the Oscars on Sunday. His turn as The Dictator – the monster at the heart of his new film – reminded me that its reported source is not so much the life as the "art" of Saddam Hussein. With the assistance of ghost-writers, the Iraqi despot published four heavy-booted allegorical novels. The Dictator, it seems, will draw on Zabibah and the King (2000).

In Saddam's medieval romance, the heroic saviour "Arab" rescues the suffering Zabibah (who represents Iraq) from the clutches of evil rapist Uncle Sam – sorry, her nameless brute of a husband. But Saddam's logic as a fabulist rather deserted him (or his team) when he called the hero's feudal antagonist Nuri Chalabi, who stands for – er, opposition leader Ahmed Chalabi.

Saddam cared enough for the prestige of literature to commission and authorise (if not author) these yarns. Likewise, Stalin and Mao never lost their taste for poetry. Benito Mussolini wrote not only a sympathetic life of the religious reformer Jan Hus but a bodice-ripper romance, The Cardinal's Mistress. As well as the political treatise of his Green Book, the late Muammar Gaddafi also published some short fiction, available as Escape to Hell and other stories.

What should we make of this recurring affinity between absolute power and the dream of authorship? Some critics might see dictatorship as a kind of real-life kitsch or pulp fiction. WH Auden, so often an inspired reader of the will to power, brackets sentimental populism with autocratic cruelty in his 1939 poem "Epitaph on a Tyrant": "Perfection, of a kind, was what he was after,/ And the poetry he invented was easy to understand". But "when he cried the little children died in the streets." Sadism and schmaltz, as Auden and later Milan Kundera suggest, have a lot in common.

Behind the eagerness of a Mussolini or Saddam to tell stories for publication, you may also detect the deep historical link between politics and print. Mass ideological movements developed in tandem with the spread of literacy and the availability of cheap reading. No wonder seekers after power soon clambered onto this loftiest of media platforms. In early-Victorian England, Benjamin Disraeli - the most durable of writer-statesmen -twin-tracked socially-aware fiction and the pursuit of high office. And, the further from metropolitan centres leaders stood, the longer that attraction to the lustre of print lasted. For all his command of TV, film, press and radio, Saddam at the turn of the millennium still bothered to put his name to novels.

Publishers, don't all rush at once – we can probably do without a tie-in edition of the book when The Dictator opens. Still, Baron Cohen has a perfect riposte to anyone who accuses him of dissolving politics into fiction. As long as professional despots choose to spin deadly fantasies, professional fantasists ought to answer back in kind. Just as, in 1940, the incomparable Chaplin did with his classic reality-check – The Great Dictator.

News from the beloved country

From an early fanfare tomorrow with William Boyd, Alain de Botton and Claire Tomalin to a closing blast on 11 March with Lynne Truss and AL Kennedy, the 'Independent' Bath Literature Festival hardly lacks highlights. Yet it keeps one final flourish in reserve for a week after the main festival. On 18 March, I will have the privilege of talking to South African Nobel laureate Nadine Gordimer as she publishes a new novel about her homeland's post-apartheid progress, No Time Like the Present. Nelson Mandela's recent health scare reminded us of how much this history matters to so many – and it has no finer creative interpreter than Gordimer (bathlitfest.org.uk).

Printed Penguins still picked up

Such is the level of hype and hysteria that now surrounds the publishing world, civilians might half-expect to see the staff of long-established firms begging on the kerb while fleets of newly-rich DIY electronic authors sweep by in their chauffered limousines. As usual, the trajectory of one big old bird – Penguin Books – gives the lie to all such fantasies. Far from waddling to its grave, Penguin (part of the Pearson group) has just posted profits of £113 million on global sales that reached £1.06 billion. And the digital portion of that deep pot? At £126 million, it makes up 12 per cent: double the previous year's e-book revenues, but still leaving 88 per cent of all income down to print. In the US, electronic editions now account for more than 20 per cent of Penguin's earnings. The UK will match that percentage, but no one has any reliable idea of where the final ceiling for e-books lies. Meanwhile, we can bet that the new Jamie Oliver title Penguin promises for next Christmas will again fly off the shelves in solid, kitchen-friendly, dead-tree form.

b.tonkin@independent.co.uk

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks