How Meryl Streep showed us why the least able have no idea of their own incompetence...

In a new book, an influential pop-philosopher William Poundstone asks if we worry too much about a supposed rise in ignorance. In this essay, he argues, we probably don’t….

A recent film, Florence Foster Jenkins, presented Meryl Streep as a tone-deaf diva who believed she was a gifted vocalist. The movie was, as publicists like to say, based on a true story. New York heiress Florence Foster Jenkins (1868–1944) had been a child prodigy pianist, enough so as to give a performance at the White House of President Rutherford B Hayes. As an adult Jenkins turned her attention to operatic singing. She began giving private recitals in 1912, at the age of 44. Her singing was so supremely bad that word got around. New York’s smart set attended just to hear how abominable her singing was. Jenkins was perpetually off-key and mangled Italian and German words.

Could Jenkins have been unaware of how bad she was, or how she was perceived? That is still debated. It’s clear she heard some in her audience snickering at her. She called them “hoodlums” and insinuated that they were hired by jealous rivals.

The peak, and nadir, of Jenkins’ career came at age 76, when she drew on her considerable wealth to book Carnegie Hall for her first and only public performance. Such luminaries as Cole Porter, Gian Carlo Menotti, and Kitty Carlise attended. So did the New York critical establishment, their knives sharpened. The reviews were merciless. Two days later Jenkins suffered a heart attack while shopping for sheet music.

Today we have a term for Jenkins’ misperception: the Dunning-Kruger effect. Named for Cornell University psychologist David Dunning and his then-grad student Justin Kruger, this is the observation that people who are untalented, unskilled, or ignorant tend to believe they are much more competent than they actually are. Thus bad drivers believe they’re good drivers, garage band guitarists think they could be rock stars, and billionaires who’ve never held public office believe they’d make a terrific president. How hard can it be?

Dunning came to this subject by way of a story every bit as odd as Jenkins’. On April 19, 1995, McArthur Wheeler robbed two Pittsburgh banks in broad daylight. He wasn’t your typical bank robber, starting with the fact that he stood 5 foot six inches and weighed 270 pounds. He did not wear a mask, and security cameras caught good images of his face. The police released the footage to the local TV news, and a tip came in almost immediately. Just after midnight, the police arrested Wheeler at his suburban home.

“But I wore the juice,” Wheeler said.

Wheeler explained that he knew lemon juice was used as invisible ink. Therefore, putting lemon juice on his face would make him invisible.

He said he tried it! Before the robbery Wheeler smeared lemon juice on his face and snapped a selfie with a Polaroid camera. There was no face in the photograph, he insisted. Wheeler must not have been any more competent at photography than at bank robbery.

Another drawback to the lemon juice was that it stung Wheeler’s eyes. He could barely see the bank tellers, though they could see him.

Wheeler’s misadventure made it into a feature on the world’s dumbest criminals. That article caught the eye of psychologist Dunning. He saw something universal in it: “The overconfident airhead is someone we’ve all met,” he told me. So he and Kruger began trying to document this.

In one study they went to a skeet-shooting competition and asked gun enthusiasts to take a firearms safety quiz prepared by the National Rifle Association. After the quiz, but before learning their score, the gun owners were also asked to estimate how well they did relative to others.

Remarkably, those who scored the worst on the quiz believed that they had done rather well, better than about two-thirds of those tested. Those who scored the highest had a more realistic notion of where they stood, though they tended to underestimate their score slightly.

The psychologists tested Cornell students on topics ranging from grammar to logic to humor. The humour quiz asked participants to rate how funny jokes are, giving two examples

First: What is big as a man, but weighs nothing? His shadow.

Second: If a kid asks where rain comes from, I think a cute thing to tell him is “God is crying.” And if he asks why God is crying, another cute thing is to tell him is “probably because of something you did.”

Most would agree that the first example is not funny, while the second (from TV comedy writer Jack Handey) is brilliant. But there is a segment of the population that is unable to make this distinction. The humourless group believed that they were better than most at judging what’s funny.

Dunning and Kruger published their results in a 1999 paper with the memorable title: “Unskilled and Unaware of It: How Difficulties in Recognising One’s Own Incompetence Lead to Inflated Self-Assessments.” Since then it’s become part of the language of psychology and indeed of the Internet. John Cleese, who knows Dunning, did a YouTube video explaining the effect in 60 seconds. Explains Cleese: “If you’re absolutely no good at something at all, then you lack exactly the skills you need to know that you’re absolutely no good at it. And this explains not just Hollywood but almost the entirety of Fox News.”

It also explains Florence Foster Jenkins. A tone-deaf singer is by definition incapable of perceiving why her singing is different from that of more conventional talents. Indeed, Jenkins insisted she was the equal of the greatest stars of the day. She often performed the most demanding of songs. Had she a better grasp of the technical details, she might have chosen a repertoire more suited to her abilities, such as they were.

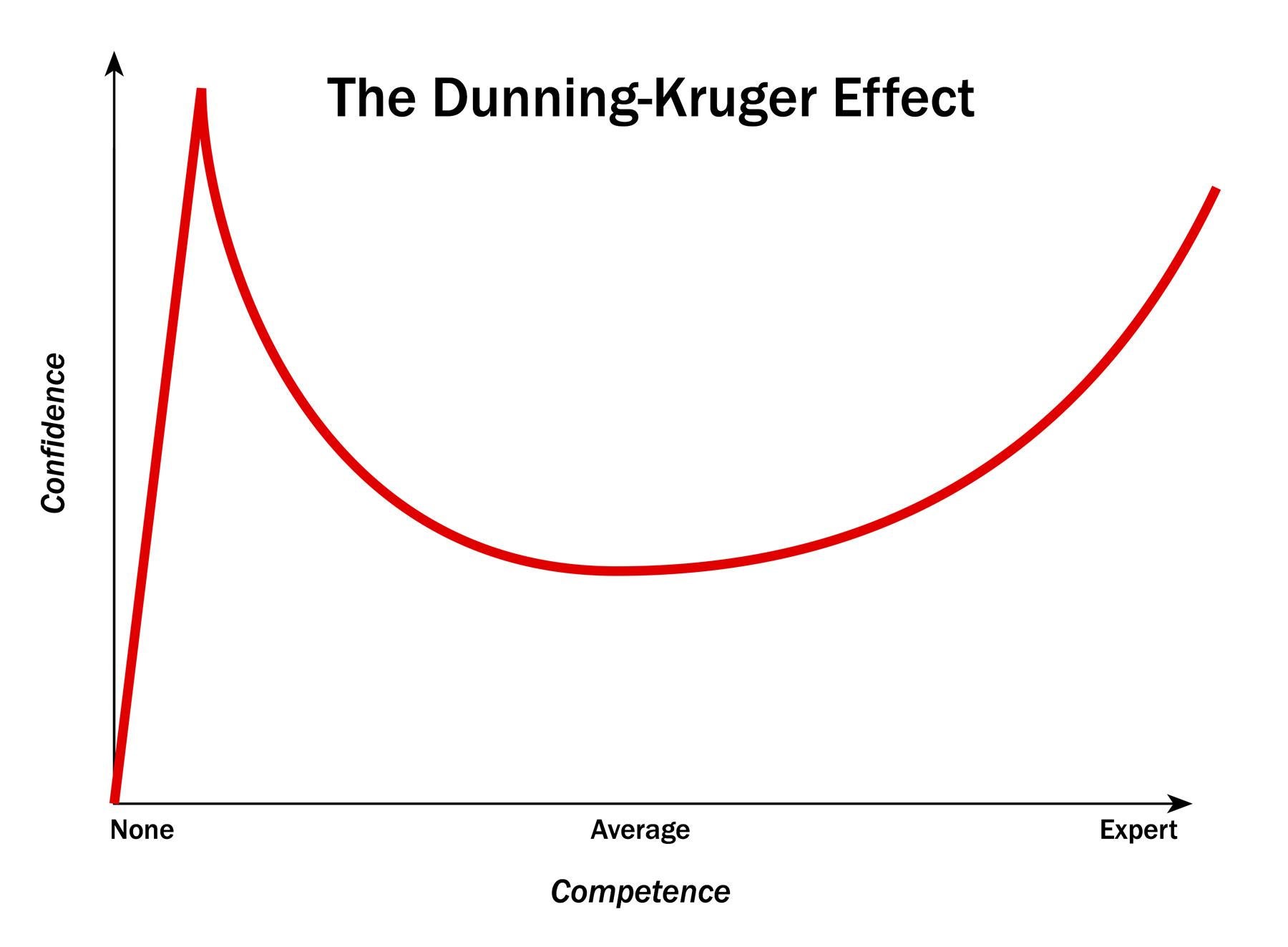

The Dunning-Kruger effect is responsible for one of my favorite charts. It’s almost an emoticon: a smile turned smirk.

The chart plots confidence against competence. It offers a clear moral: A little knowledge is a dangerous thing. When you have no knowledge or experience whatsoever in a particular field, it’s usually easy to recognise your limitation. I’ve never touched a violin in my life. I don’t expect to pick one up and begin playing. My confidence in my ability is very properly nil. Likewise, as Dunning and Kruger have it in their 1999 paper, “most people have no trouble identifying their inability to translate Slovenian proverbs, reconstruct a V-8 engine, or diagnose acute disseminated encephalomyelitis.”

But those who have a little knowledge or experience often think they know it all. That accounts for the steep slope at far left and sharp peak. Florence Foster Jenkins and McArthur Wheeler would be somewhere near the top of the hairpin.

Those with more talent or expertise are better able to comprehend their limitations. They know what they don’t know; they understand where their skill set is lacking. They appreciate how other people truly are better at some things than they are. Confidence levels reach a minimum, in the centre of the chart’s “smile.”

Finally, those who are truly experts know they’re good. The curve slants upward to the right. Those at the level of a Maria Callas recognise their expertise—though don’t necessarily have the supreme confidence of the ignoramus. A genius is aware of her imperfections, even though they may go unnoticed by practically everyone else. Few listeners are qualified to perceive where Callas fell slightly off her game.

It is easy to smirk at the overconfidence of the untalented. But to do that is to miss the discomforting message of Dunning and Kruger’s research. In 2003 they and colleagues Kerri Johnson and Joyce Ehrlinger wrote that the research “calls into question whether people are, or ever can be, in a position to form accurate self-impressions. If incompetent individuals do not have the skills necessary to achieve insight into their plight, how can they be expected to achieve accurate self-views? How can anybody be sure that he or she is not in the same position?”

An obvious corrective is to have a social network willing to speak the truth. Florence Foster Jenkins was insulated from the reality of her incompetence by a trust fund, a doting husband and a long-suffering voice coach. I would guess that McArthur Wheeler didn’t solicit much feedback on his invisibility scheme. The remedy, then, ought to be simple: avoid enablers and yes-men; cultivate friends who can be brutally honest; read your reviews, online and otherwise.

That’s not a bad prescription, but neither is it a panacea. Critics hated Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring at its first performance. The scientific establishment doubted that heavier-than-air flight was possible. Young Einstein couldn’t get a teaching job, and nobody cared much about what van Gogh was doing except for a doting brother. Friends and critics might not recognise true genius, in the unlikely event one possesses it.

You may not harbour illusions about your ability to belt out Verdi. Yet in the tragicomic biopic of life, we all suffer from delusions of competence, in ways small and large. The Dunning-Kruger effect is not a pathological condition –

it is the human condition.

William Poundstone is the author of ‘Head in the Cloud: The Power of Knowledge in the Age of Google’ (Oneworld Paperback Original, £12.99) published on 1 September

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies