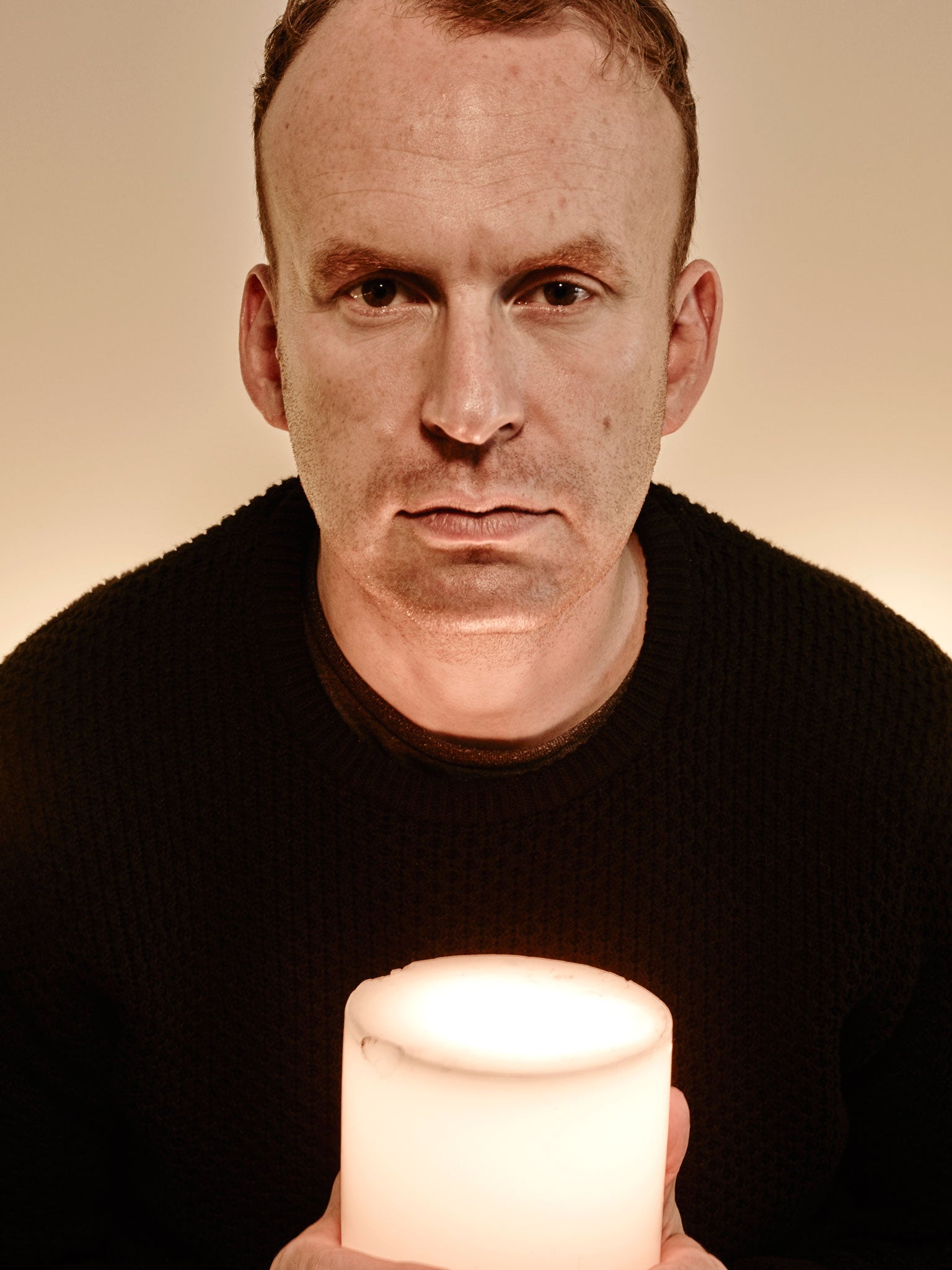

Matt Haig interview: The writer hopes his new book will help him banish the ghosts of Christmas past

The festive season hasn't always been a joyous time for the author, who has written a novel revealing the tragic history of Santa Claus himself

It could hardly be less festive. A coffee shop in the Royal Institute of British Architects on a cold, overcast November morning. But the cool marble façade is not stopping bestselling author Matt Haig from revisiting some Yuletide memories…

Matt Haig's Ghost of Christmas Past #1. It was the night before Christmas circa 1990, years before Haig became the bestselling author of the wryly humorous The Humans and his part-autobiography, part self-help book Reasons to Stay Alive. Back then, he was simply a 15-year-old getting sozzled on Christmas Eve with his best friend, whose parents ran the local Chinese takeaway. "We decided it would be a great idea to go to Midnight Mass. We were laughing at the carols, singing the wrong words. We weren't being abusive. We were just drunk."

They were also unaware that Haig's parents were standing two rows behind. Next to them was their appalled French teacher. "She said, 'I must apologise about those two boys. They are from our school.' My mum replied, 'I'm pretty embarrassed too. That boy's my son.'"

Enough nervous laughter accompanies this anecdote to suggest that, a quarter of a century on, the embarrassment has not dissipated completely. For Haig, Christmas is a way to review his formative years. "You can almost mark that journey towards adulthood in feelings towards Christmas. That fading away as a teenager, then Christmas meaning almost nothing except getting drunk in your twenties. With children it comes back. I long to reclaim that feeling."

Haig describes "that feeling" as "a belief in magic and feeling close to magic".This is the subject of Matt Haig's Ghost of Christmas Past #2: the first joyful glimpse of a suddenly full Christmas stocking hanging from the bedroom door. "You knew there would be presents by the tree from relatives, but there was nothing to beat the idea that someone came down your chimney. On one level it is a lie parents tell their children. On another, it is about allowing them to believe in magic, mystery, hope and wonder. All those things are real in different ways."

Taken together, these two memories offer snapshots of Haig's early life. Born in Sheffield, he enjoyed an idyllic childhood, growing up in a village beside a canal. When Haig was seven, his father's job transplanted the family to Newark, Nottinghamshire. Life became the stuff of a Roald Dahl story. School was rougher, teachers were horrible and Haig became an "outsider".

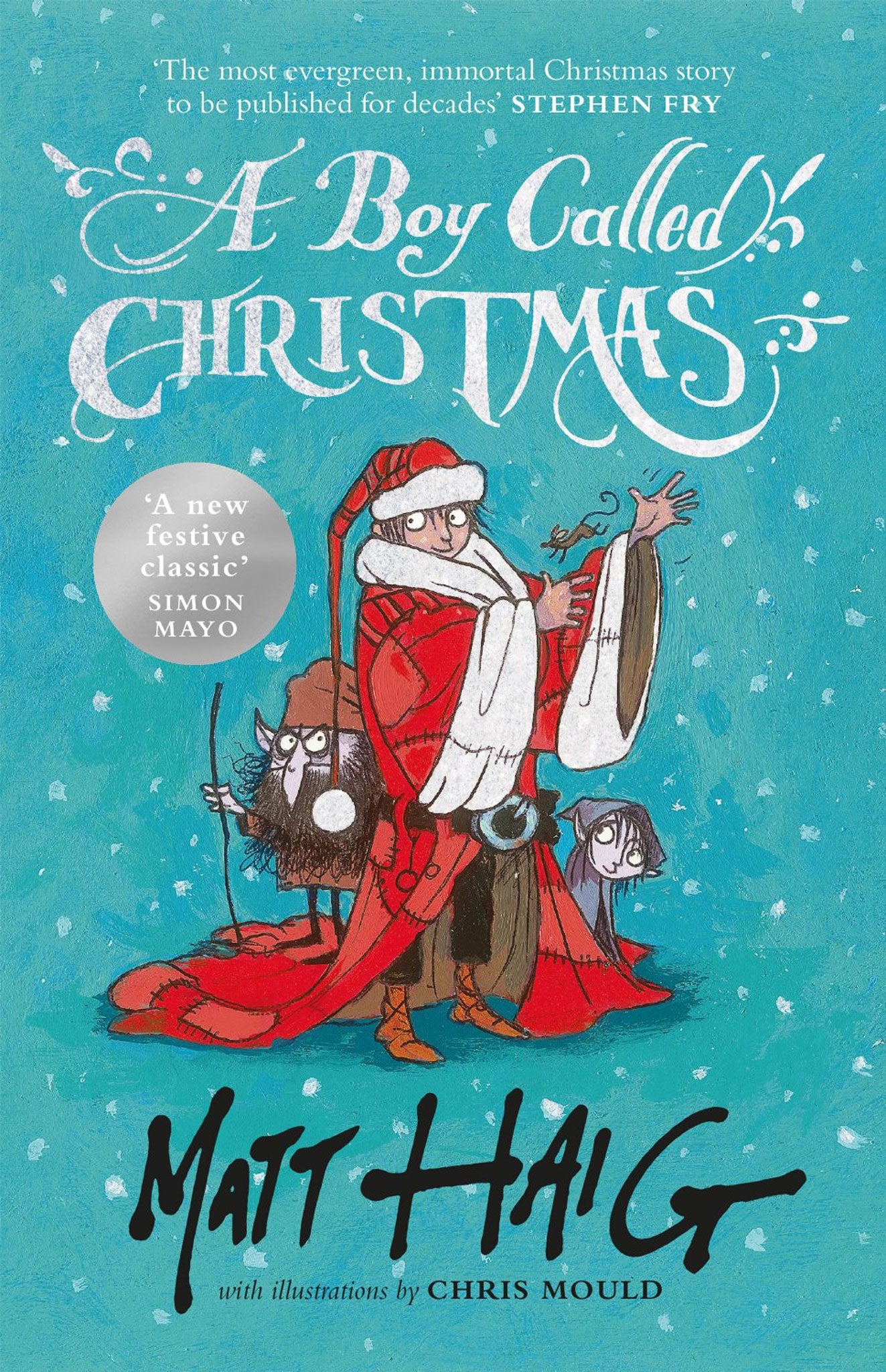

Christmas might help Haig narrate his 40 years, but now Haig has returned the favour and narrated Christmas. His new book, A Boy Called Christmas, is a sparky novel aimed at children of all ages that does for Santa Claus what Christopher Nolan did for Batman. Haig's hero is Nikolas, an astonishingly cheerful 11-year-old whose adventures present him with all the accoutrements he needs to become the great gift-giver in the sky: a red hat, a powerful attachment to chimneys, flying reindeer and, of course, elves.

This "Father Christmas Begins" is a hymn to one of Haig's favourite subjects: belief. I'm not sure whether it's the unreconstructed child in Haig or the unreconstructed novelist, but his Father Christmas is imaginary in the most positive sense. In his opinion, our faith creates the character, rather than the other way around. "I think Father Christmas is real because the belief is real. The belief becomes the reality."

This begs one question: did Haig believe in an actual Father Christmas? "I was 11 at secondary school when I stopped. It was a teacher who told me. I was dying inside. I knew my younger sister didn't believe. It was a stubborn faith."

This stubborn faith has been passed down to Haig's children, seven-year-old Lucas and six-year-old Pearl. It was Lucas's fascination with understanding Santa's backstory that inspired his father's new novel. "He totally believes in magic and Father Christmas, but he has lots of questions about it – including whether Father Christmas was ever a boy."

Responding with a novel had other benefits, not least as a counterbalance to Haig's Reasons to Live, a frank examination of his experience of chronic depression and anxiety, published in March this year. "I had written about the darkest period in my life. The writing hadn't been too hard but I knew I was going to spend a year having these public therapy sessions. To keep me sane and happy I thought, 'What is the most fun I can have writing?' An origin story of Father Christmas was the one that was there."

Written during the winter of 2014, it was, Haig adds, "a way to enjoy last Christmas". Read in these contexts, A Boy Called Christmas could be interpreted as a fable about surviving sadness and depression. The eventual happy ending is achieved not despite the novel's sad moments, but because of them. Take Nikolas's most painful memory: the death of his mother, who falls into a well while escaping a ferocious grizzly bear. Haig himself hints at the well's symbolic possibilities when describing the depths of his own despair.

"In its complete form, depression takes away all hope. It gives you the most negative world view. I think it is a luxury and privilege to be sane and well and pessimistic. Because with depression, you have no other option. You don't want that pessimism, because it is crushing you and keeping you down at the bottom of the well."

This speech concludes Matt Haig's Ghost of Christmas Past #3. It is Christmas Eve, 1999. Two months earlier, on 13 September, he had suffered the breakdown that brought on his first bout of chronic depression. "I was at my parents' house. I can remember they were making food. They had sent me and Andrea [now Haig's wife] into town. I was having a panic attack in the town centre on Christmas Eve, which wasn't a rare thing for me at that point. It felt horrendous to be feeling like a nightmare when everything around me looked like a dream."

That festivity is no protection against loneliness, melancholy and grief is one reason Haig loves Frank Capra's It's a Wonderful Life. "It brings everyone into Christmas, which is a very depressing and isolating time for a lot of people. The first time I ever heard about anyone taking their own life was on Christmas Day when I was a child." (The person in question was an acquaintance of Haig's mother.)

Back in 1999, the pressure to be merry provided a poignant counterpoint to his feelings; he talks with humbling clarity about being unable to enjoy food and drink ("Eating a pudding could feel bad"). Far worse was an unnerving sense of isolation.

"It was difficult not because I was alone, but because I wasn't. I was having to play-act being normal while feeling very unnormal and intense. I was often at my most extremely isolated in situations when I should have been the opposite. I had parents. I had family. I had presents. I had physical comfort. But I was totally despairing."

Since 1999, Haig has recovered from 22 separate bouts of depression. Experience and time have lent him the confidence to take each inevitable setback in his stride. He recalls the strength he gradually gained by ticking off every day he survived after that initial crisis. "It was a psychological Advent calendar. When I got into the twenties it gave me some form of hope. Even now I say it is 16 years. Time is honestly the best weapon against depression."

Today's Matt Haig is, to quote Ebenezer Scrooge, not the man he was. "Depression told me I wouldn't be alive at 25. Depression convinced me that if I was alive, I'd be in a straitjacket and a padded cell. I had these views of reality that were wrong. My pessimism was wrong."

Optimism, by contrast, "is medicine", something that has ensured he is not the writer he was, either. "My early novels were written in quite a dark place. I stand by them, but I would never write them again. I think it is subversive to embrace emotional optimism, because it goes against the grain."

This outlook – positive, a little sentimental but not at the expense of realism – is writ large on every page of A Boy Called Christmas. A sequel – A Girl Called Christmas – is already in the works, as is a possible film adaptation.

So, what about Christmas 2015? What might become Matt Haig's Ghost of Christmas #4? "Our children are obsessed with Christmas. We will try to do magical things with them." Family, ice-skating, movies and books are all seasonal staples. Haig, who has just turned 40, jokes about receiving a midlife crisis as a gift, but looks forward to a period of sensory indulgence. "Increasingly, the adult way to enjoy Christmas is food-related. A green card to escape the pressure of the quinoa. Christmas is a carnival, isn't it?"

What if it promises to be less cheerful? "I think culture can be a great comfort, a way of getting the Christmas spirit." This is not a matter of superficial escapism, but reflects a deeply held faith in art, and literature above all.

Here is one final Matt Haig Ghost of Christmas. It is that same bleak December in 1999. Struggling to articulate anything at all, Andrea suggests he write as a way to "stay in the world". He starts with his name, before attempting the "lyrics of the worst Iron Maiden song" to express his emotions. "I don't have the answers to this, but it is something to do with language being a shared thing that links us as a species. The threat of not talking about bad stuff builds up. That fear of being disconnected. Writing and reading felt like an umbilical cord back to the world."

A Boy Called Christmas will doubtless soon appear, as if by magic, in festive stockings across the world. I do believe Haig when he says that the real gift is "giving other people optimism. If you can't give children optimism, then what are you doing?"

'A Boy Called Christmas' is published by Canongate, priced £12.99

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks