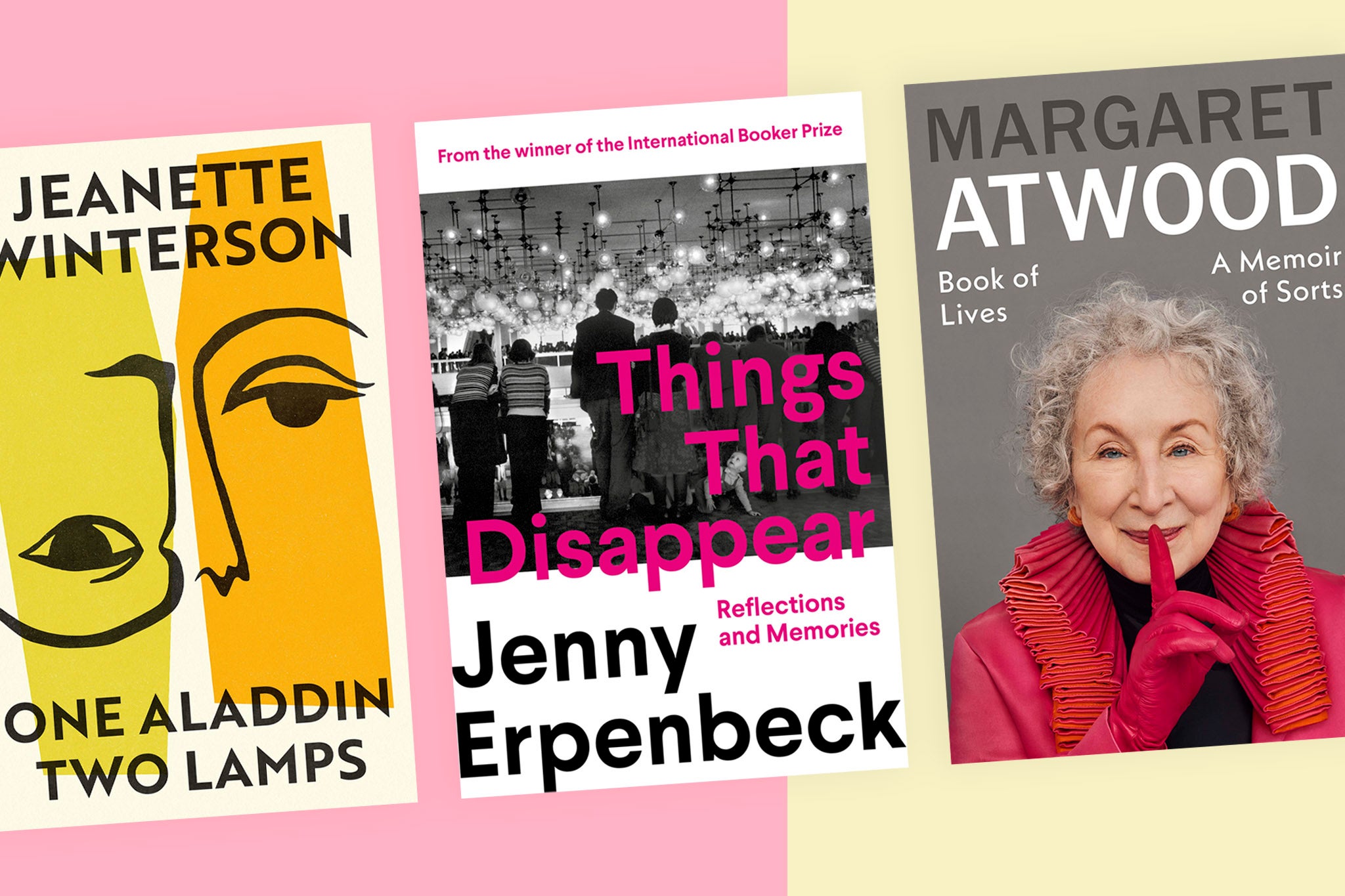

Books of the Month: What to read this November, from Margaret Atwood’s memoir to Jeanette Winterson’s five-star fiction

Martin Chilton shares his November reading highlights

In her lyrical, moving memoir Bread of Angels (Bloomsbury), rock goddess Patti Smith tells the story of how she “found her voice” – both the singing and writing kind. Music fans will also find much of interest in Paul Vallely’s Live Aid – The Definitive 40-Year Story, a detailed, potent account of the memorable 1985 rock concert to raise money for victims of the famine in Ethiopia.

Two history books caught my eye this month. Dan Cruickshank’s The English House: A History in Eight Buildings (Hutchinson Heinemann) condenses the intriguing story of how English homes have developed. Some things seem permanently rotten, however: he reminds modern readers that greedy property speculators and landlords were described in an 1892 book as “the vampyres of the poor”. Cruickshank has also written the introduction to Philip Davies’s stunning photographic book Panoramas of Lost London: Work, Wealth, Poverty and Change 1870-1945 (Atlantic Publishing, in association with Historic England), which includes some startling images of the dilapidated houses the anaemic poor had to endure during the late-Victorian era.

Finally, if you are looking for a judicious analysis of why democratic ideas are being undermined in the UK and US, then I would recommend AC Grayling’s For the People: Fighting Authoritarianism, Saving Democracy (Oneworld).

The choices for memoir, novel and non-fiction book of the month are reviewed in full below:

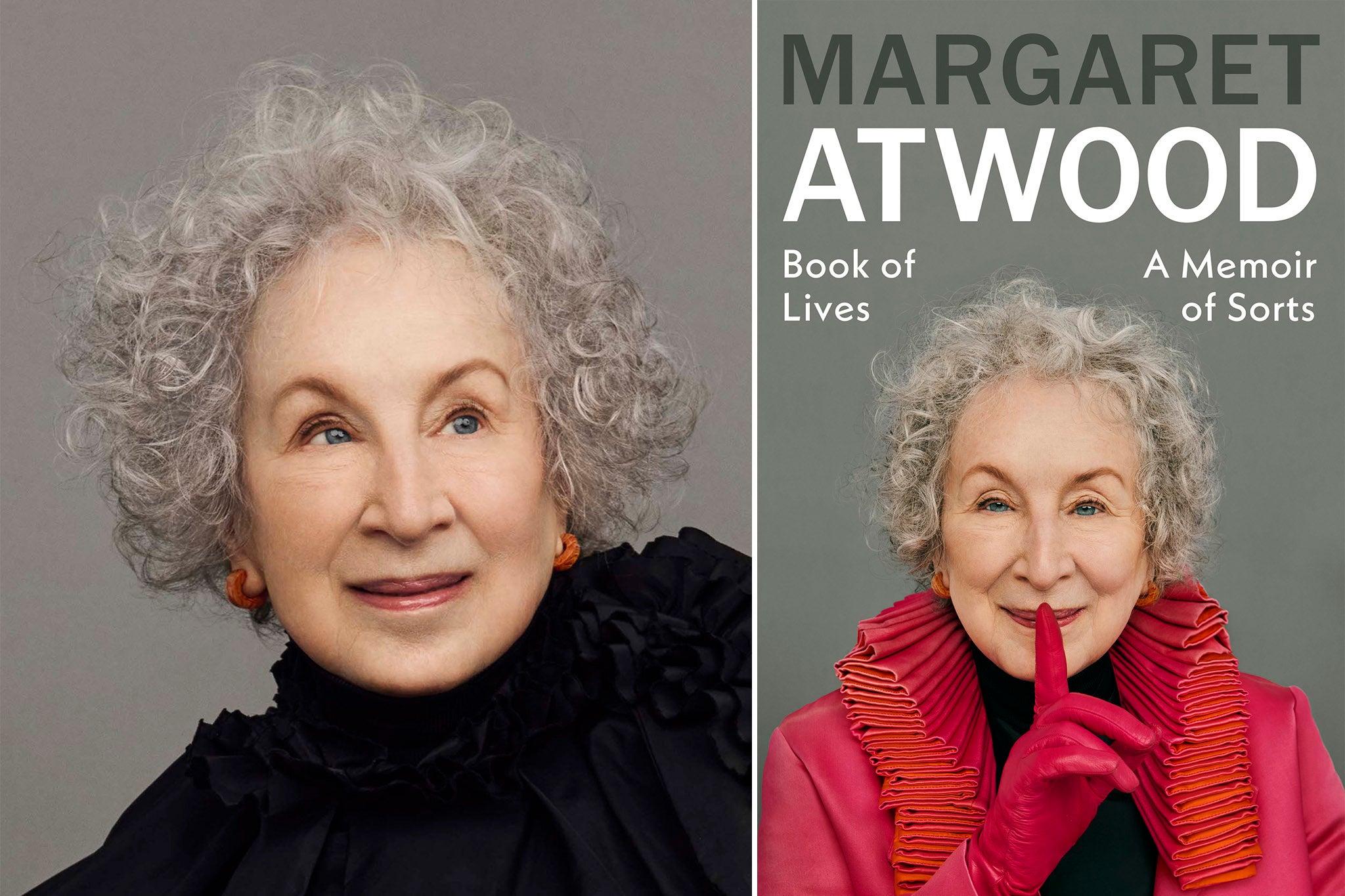

Memoir of the Month: Book of Lives: A Memoir of Sorts by Margaret Atwood

★★★★☆

Margaret Atwood jokes that writing a memoir not only offers the chance to cast a “gauzy haze over my stupider or wickeder actions”, but also the platform to trash enemies and “pay off scores long forgotten by everyone but me”.

In the 600-page autobiography she calls “a memoir of sorts”, the Canadian writer is far too canny to reveal anything more than she really intends. Nevertheless, the text is overwhelmingly generous rather than score-settling, and the punches, when they are thrown, seem deserved and are delivered with wit. Example: “‘She writes like a man,’ a fellow poet said of me in the early 1970s, intending a compliment. ‘You forgot the punctuation,’ I told him. ‘What you meant was ‘She writes. Like a man.’” The author’s level-headed, albeit unconventional, upbringing perhaps helped her cope when she encountered “backstabbing” poets, embittered critics delivering “hit job” reviews, and some of the “viciousness” of academia she faced during spells as a lecturer.

Devotees of her fiction will be particularly engrossed by her background information on majestic novels such as Cat’s Eye, The Handmaid’s Tale, The Testaments and The Blind Assassin – and her “gloomy” unpublished early novel Up in the Air so Blue. Fame brings all sorts of fans, however, including the one who bizarrely asked her in a letter: “Why is your mouth so small?” A lot of readers also seem to want to tell her why Cat’s Eye, a tale of the spiteful schoolgirl Cordelia and her gang, resonates so powerfully and personally. Atwood, who based the novel on her own playground experiences, is even-handed about the universality of cruelty displayed by women and men, noting that “grown men can be as Machiavellian as nine-year-old girls”.

Atwood describes her past and her emotional life in sharp, droll detail throughout and there is much fun to be had in her accounts of the many visits to England she’s made over the years. She recalls of the first trip in 1964 that the “budget food” was quite awful, adding: “Hamburgers tasted like rancid lamb fat.”

Her long-term lover, the writer Graeme Gibson, is the chief second character of the memoir, although a cast of fascinating names are also in the mix, including author Jean Rhys and fellow Canadian writers Mordecai Richler, Robertson Davies and Alice Munro. Nobel laureate Munro stayed with her partner Gerry Fremlin after learning that he had allegedly molested Munro’s nine-year-old daughter. “We didn’t discuss personal subjects. Now I know why,” Atwood states of their friendship. She finds a smart and jocular way to be candid about her personal life in sections where she writes to her own “Dear Inner Advice Columnist” column. The brusque replies she pens are splendid.

The scope of Atwood’s fluently written memoir is impressively wide and takes in surviving lockdown, what happens when you live in a supposedly haunted house, and the trials and tribulations of living in Canada’s wildest areas. The ruler across the border, Donald Trump, barely features, although the offhand comment that “As Offred says in The Handmaid’s Tale, there is always a Resistance,” speaks volumes.

Book of Lives: A Memoir of Sorts is probably best enjoyed slowly, and Atwood, who turns 86 this month, is enjoyable company as she reminisces. You even discover why she owes her very existence to a large green caterpillar. There are a few neat, folksy moments, too. “Never go swimming when a thunderstorm is brewing. I’m telling you this for your own good,” she advises, in a book with understated voltage.

‘Book of Lives: A Memoir of Sorts’ by Margaret Atwood is published by Chatto & Windus on 4 November, £30

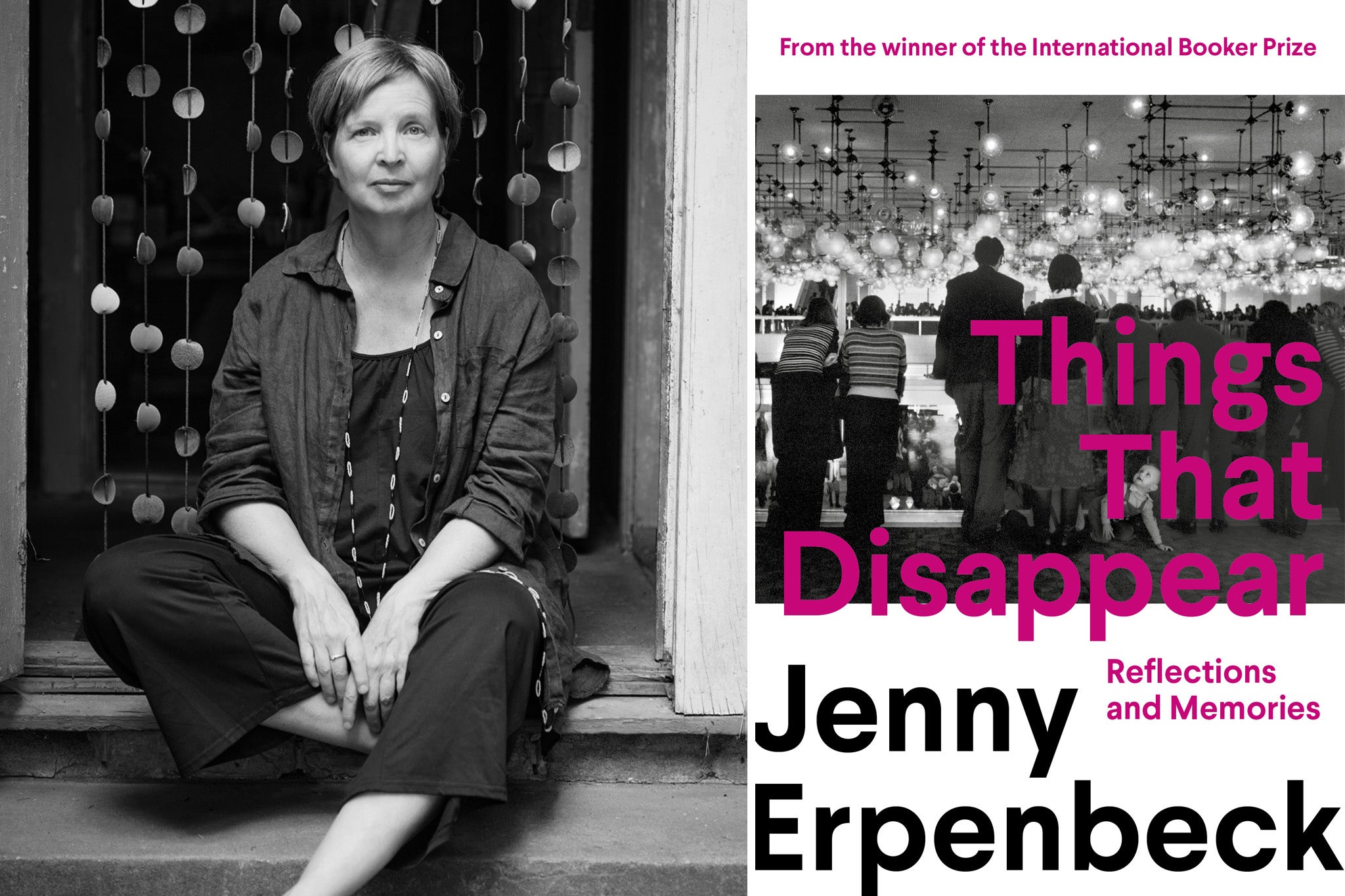

Non-Fiction Book of the Month: Things That Disappear by Jenny Erpenbeck

★★★☆☆

Jenny Erpenbeck, who was born in East Berlin in 1967, was awarded the International Booker Prize for her 2024 novel Kairos. As well as being a talented fiction writer, she is an accomplished newspaper columnist. A series of essays written for the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung are collected in Things That Disappear, translated from the German by Kurt Beals.

I enjoyed Erpenbeck’s quirky reflections and her columns go to some strange places, including the sandbox of her son’s nursery school, a place where “rather enormous teeth” are discovered. The “things that disappear” will eventually include Erpenbeck herself, of course, and she acknowledges wryly that “I’ve already considered whether anyone will remember the way I blow my nose, or the way I watch a boxing match on TV, or my knees.”

Other random musings include those on vanishing socks, expensive cheese, friendship, cemeteries, Christmas present shopping and the appeal of Beethoven. If you are a bakery junkie, you will find much to enjoy in the essay “Splitterbrötchen”.

Less is definitely more with Things That Disappear and there is melancholy wisdom about ageing in the two-page essay “Youth”, with Erpenbeck offering that age-old lament: where does all the time go?

‘Things That Disappear’ by Jenny Erpenbeck is published by Granta on 6 November, £12.99

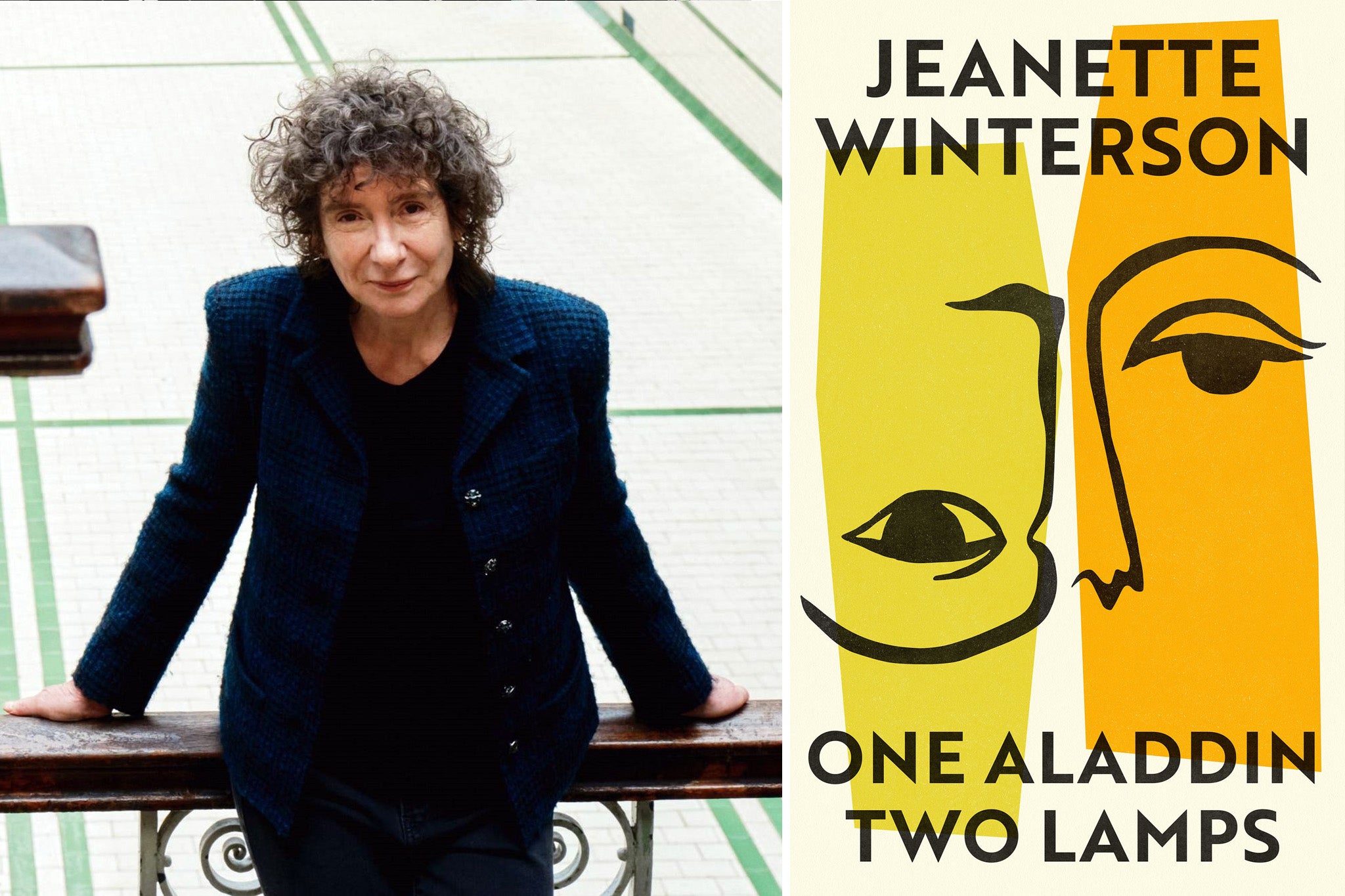

Novel of the Month: One Aladdin Two Lamps by Jeanette Winterson

★★★★★

It would be more accurate to describe Jeanette Winterson’s One Aladdin Two Lamps as our “Sort of Novel” of the month, because her new book is a dazzling blend of fiction, memoir, essay and magical storytelling. Drawing on the fables of Shahrazad, the legendary narrator of One Thousand and One Nights, Winterson rolls out stories, opinions and reminiscences like a flying carpet.

Winterson deftly draws on stories from the Middle Eastern folktale to ruminate on the power of the internet, where “millions cluster around ideas rotten at the core – like flies on a carcass”. The imaginative deployment of stories from the One Thousand and One Nights made me want to read them all afresh.

Using the guise of a modern Aladdin, Winterson is open and funny about some of the miseries of her past. Her own Pentecostal “mother” – evoked so memorably as the bullying adoptive parent in her semi-autobiographical 1985 novel Oranges Are Not the Only Fruit – is described as “an introverted and unhappy woman”. Biting as the family moments are, though, the book works best as a highly original dissection of some of the pressing philosophical questions of our queasy age: Who can escape their fate? Why are humans (well, men) so addicted to war and violence? Why is alienation the modern disease? Who can any of us really trust? Why are people so attached to objects as status symbols?

Above all, One Aladdin Two Lamps is a riveting look at humanity at an existential crossroads, at a time when (she argues with conviction) a new war on women is underway. Winterson’s strength here is not only to evaluate why stories captivate us, but also to bring home why books are so important in showing us all the blurred lines between fact and fiction.

‘One Aladdin Two Lamps’ by Jeanette Winterson is published by Jonathan Cape on 13 November, £18.88

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks