The best summer reads: 90 books chosen by 40 literary luminaries

From Harper Lee to Hilary Mantel, and poetry to parallel universes, here’s a holiday library of unmissable books chosen by authors, critics, publishers and more

What to read on your recliner this summer? While we await the biggest event publication of the year with Harper Lee’s Go Set a Watchman, in mid-July, along with the controversy it will inevitably ignite, we might refresh our memories of Scout and Atticus with the recently reissued sequel, To Kill a Mockingbird. Or that other big summer excitement, The Girl in a Spider’s Web, the fourth instalment in the Millennium series (though of course not by Stieg Larsson), in August.

Among summer’s major publications is, at one end of the spectrum, Milan Kundera’s The Festival of Insignificance, a shaggy-dog story and his first novel in 14 years, while at the other is Candace Bushnell’s Killing Monica, which features a New York novelist grown sick of her fictive creation who has taken on a life of her own in the lucrative Hollywood film adaptations of her books. It makes no mention of Sex and the City, but is it a meta-fictive reference to Carrie Bradshaw’s journey from book heroine to screen franchise?

Highbrow literary fiction or otherwise, it’s not always the new that has the greatest lure. Among the novelists, critics and publishers in these pages who reveal the books they will be packing for the summer is a rich mix of classics that will either be re-visited or opened for the first time, from Mikhail Bulgakov’s The Master and Margarita to Alice in Wonderland. Many who are determined to catch up on the best of spring reading cite Kazuo Ishiguro’s fantasy novel, The Buried Giant as well as Kate Atkinson’s A God in Ruins.

My own summer reading list is already hopelessly overcrowded: Roberto Saviano’s Zero, Zero, Zero, a typically intrepid, in-depth investigation into narco-traffickers; It’s All in Your Head, Suzanne O’Sullivan’s investigations into psychosomatic or “imaginary illnesses”; and Sunjeev Sahota’s second novel, The Year of the Runaway. Named in 2013 among Granta’s Best of Young British Novelists, Sahota here grapples with the hopes and disappointments of Indian immigrants newly arrived in Sheffield.

To add to the mix: Tasha Kavanagh’s thrilling-sounding debut novel about teenage loneliness and obsession in Things We Have in Common and an intriguing re-publication of The New Sorrows of Young W by Ulrich Plenzdorf, described as the “East German Catcher in the Rye”. Oh, and Evie Wyld’s curious graphic memoir which combines her life story with her childhood obsession with sharks, Everything is Teeth. To top off the summer, this month’s Independent Foreign Fiction Prize winner, The End of Days, by Jenny Erpenbeck, is an absolute must-read. It has stunned and moved everyone who has read it. Then to autumn reading with new fictions from Margaret Atwood, Jonathan Franzen, William Boyd, Salman Rushdie and so many more…

Introduction by Arifa Akbar, Literary Editor

Kate Atkinson, novelist

The 150th anniversary of its publication will probably prompt many people to revisit Alice in Wonderland and its companion, Through the Looking-Glass, published several years later. I think Through the Looking-Glass is my favourite of the two, although when I was a child I never read one without the other as they existed side by side in the same volume, one of the few childhood books I still possess. I return to it often and will do so again this summer.

It is a book stuffed with riddles, jokes, songs, poems, parodies, puzzles. There is philosophical logic, there are mathematical concepts – a veritable authorial playground in fact. But at heart it is a fairy tale – a clever, resourceful girl undergoing a series of trials in a bizarre and often threatening otherworld.

As a writer I have learnt from Alice in Wonderland the art of the interior monologue – Alice constantly converses with herself. I have learnt that a mouse’s tale really can be in the shape of a tail (one imagines Sterne would have enjoyed this wonderland). I have learnt that anything is possible in fiction, the only boundaries are the limits of the imagination. I have learnt that words are playful and that unpleasant characters can be very funny but the best advice, of course, is provided by the King. “‘Begin at the beginning,’ the King said, very gravely, ‘and go on till you come to the end: then stop.’”

Kate Atkinson’s latest book is ‘A God in Ruins’ (Doubleday)

Lee Hall, novelist and playwright

I have a regular order with the wonderful poetry publisher Bloodaxe Books to get everything they publish. So summer is spent catching up but I’m particularly looking forward to receiving their upcoming anthology Funny Ha-Ha, Funny Peculiar, which is a compilation of humorous verse.

I’ve already peeked at Jane Hirshfield’s wonderful new collection The Beauty – but they are meditations you can reread forever. And I’ve just sent away for The Beautiful Librarians by Sean O’Brien, who always makes me laugh out loud as well as takes my breath away. As I’ll be in Edinburgh this summer doing a play at the Traverse Theatre, I thought I’d take Nan Shepherd’s In the Cairngorms. I’ve just read her astonishing The Living Mountain. Her poems have been out of print since the 1930s but are being reissued this summer by Cambridge’s tiny Galileo Publishing. And I will make my usual pilgrimage to Edinburgh’s Word Power Books, whose recommendations are always spot on.

Lee Hall’s production of ‘Shakespeare in Love’ was at the Noël Coward Theatre, London

SJ Watson, novelist

There’s a couple of debuts I’m excited about getting my hands on this summer. The first is The A-Z of You and Me by James Hannah. It sounds intriguing, and it’s central idea is so clever – the recollections of a whole life told through an alphabetical list of body parts – that I can’t wait to see what it’s like. The second is Benjamin Johncock’s The Last Pilot. I’ve been following Johncock’s progress on Twitter as he wrote this, so I’d be intrigued to read it anyway, but the fact that it’s about a US Air Force pilot during the early days of the space race makes it, for me, doubly exciting. Finally, I like to re-read a favourite during the summer, and this year I’m going to go for Rebecca, for no reason other than it’s wonderful.

SJ Watson’s new novel is ‘Second Life’ (Doubleday)

Sean O’Brien, poet and critic

I’ll be doing some re-reading. Ezra Pound’s version of Chinese poems, Cathay, appeared a century ago. Their accuracy may be dubious but they’re definitely poems, still bracing and mysterious. TS Eliot’s The Waste Land is being re-issued to mark the 50th anniversary of his death: time for another immersion.

Eliot and Pound both look back to Dante, so Prue Shaw’s Reading Dante is on the list. And I’ll be revisiting Auden’s poems, awaiting the republication of his mad, brilliant 1932 “English Study” The Orators, which opens with a school-prize-day speech harking back to Dante’s Purgatorio in order to describe “England, this country of ours where nobody is well”. Sound familiar?

Sean O’Brien’s latest collection is ‘The Beautiful Librarians’ (Picador)

David Baddiel, comedian, novelist and presenter

The book I’m looking forward to reading over the summer is Purity by Jonathan Franzen. Along with the plaudits, Franzen gets a fair amount of stick, a sense perhaps that he gives off, both in his interviews and his writing, of literary entitlement, of being to the mantle of Greatest Living Writer born. But actually, in a world where that kind of Greatness doesn’t exist any more – no one is Bellow, Updike or Roth now, not even Roth – he may still deserve a high place in what’s left of the pantheon.

In an old-fashioned novelistic way, his books are always a pleasure to read, with engaging characters, stories that hook you in, brilliant phrase-making, and an acute eye for the zeitgeist. Plus they’re funny, and not in a literary way (code for “won’t actually make you laugh”). They are very big, always – and since I already own an advance copy of Purity, I can tell you it’s no exception (in fact, I’ve already read a bit where he makes meta-fun of the modern American author’s need to write The Big Book) – which can be a bit of a problem on the beach, however.

David Baddiel’s debut children’s book, ‘The Parent Agency’, is out now (Harper Collins)

Marion Coutts, artist and writer

I first encountered Miriam Toews on the shortlist of the Wellcome Prize when we spoke together on a panel and I liked what she said. Toews is pronounced “taves”, to rhyme with waves. Her book All My Puny Sorrows is the story of two sisters, one with everything to play for: the other doing less well. But the successful one wants to kill herself and this is the condition of her existence.

All My Puny Sorrows looks at the complexity of despair and the ethics of assisted suicide. It is fiction that closely tracks the contours of autobiography and is good on the singularity of family life – the family come from a Canadian Mennonite community. Toews navigates the long legacy of depression with empathy and manages to be very funny with it, without the humour seeming at all contrived. Quite a feat.

Marion Coutt’s memoir ‘The Iceberg’ (Atlantic) won the 2015 Wellcome Book Prize

Razia Iqbal, BBC presenter and broadcaster

“If you fancy a rip roaring story rich with history, an erudite critique of colonialism, funny and full of contemporary parallels, you could try Amitav Ghosh’s third in his Ibis trilogy, Flood of Fire, about the Opium wars. For something more quietly meditative, and actually, a seriously important book, I am recommending Marion Coutts’ memoir, The Iceberg. I was on the Wellcome Book panel which chose it as the 2015 winner. It is lyrical, and deeply moving and though, about dealing with the death of a loved one, it manages to be so uplifting; I guarantee you will feel changed by the end of it.

Among the brilliant novels on the Wellcome short list, I adored Miriam Toews’ All My Puny Sorrows. It is one of the most remarkable books I’ve read on depression and its impact on the patient and family; and if you’re thinking that’s the last thing I need in a deck chair, sunning myself, think again: it is full of sass and so smart in its black humour. Two masters in their own way: Anne Tyler’s A Spool of Blue Thread, is as good as anything she has ever written. Impressive to be so consistently brilliant on writing about the American family. And, after his death last year, I started to re-read Gabriel Garcia Marquez’ One Hundred Years of Solitude, and dip into it periodically; it is a truly enjoyable way to remind oneself of his brilliance, one chapter at a time.”

Tracy Chevalier, novelist

The literary event of summer 2015 is the publication of Harper Lee’s “new” novel Go Set a Watchman. Part of the first draft of the novel that became To Kill a Mockingbird, it depicts Scout living in New York as an adult and clashing with her father. Apparently, when the editor read the draft in the 1950s, she suggested Lee leave aside the adult section and focus on Scout’s childhood. The result was the classic To Kill a Mockingbird. This may well mean that the recently discovered manuscript is no good – Lee has not edited it – but I can’t help it, I will be scratching at the door of my local bookshop the morning it comes out.

Its publication gives me the opportunity to re-read Mockingbird. The big question is whether to read it first and then Watchman, which makes chronological sense. Or read what is likely to be inferior, then follow up with the fierce genius of Mockingbird.

Tracy Chevalier’s latest novel is ‘The Last Runaway’ (HarperCollins)

David Mitchell, novelist

I have three books at the front of my summer reading list. The first is by the cultural polymath Jon Ronson, whose So You’ve Been Publicly Shamed explores the very “now” phenomenon of witch-hunts, character assassinations and public stoning via the internet. Second is the brilliant Kate Atkinson’s A God in Ruins. I’ve come to the party embarrassingly late, but having wolfed down Life After Life last month, I can’t wait to spend days of my reading life in the second panel of Atkinson’s grand, bewitching diptych. She’s a major writer by any measure. Third up is Robert MacFarlane’s new one, Landmarks. I’ll read anything MacFarlane writes. His books are calming, sane, wise and lasting: a textual antidote for a world that is too often vexed, deranged, self-harming and ephemeral.

David Mitchell’s latest book is the Man Booker shortlisted ‘The Bone Clocks’ (Sceptre)

Kate Mosse, novelist and founder of Baileys Women’s Prize for Fiction

For me, summer reading is always about ancient and modern, rest and relaxation and fun rather than “ought to” reads or “should have” reads. So, top of my list is Manda Scott’s new time-slip novel, Into the Fire, which switches between the 15th century and Joan of Arc to present-day Orléans and a police officer dealing with a very contemporary case of arson, terrorism and murder: strong female characters, it promises to be a real humdinger of a thriller.

After all that blood and mayhem, I’ll try something a little more sedate in the form of Agatha Christie. To mark Christie’s 125th anniversary, a campaign to find the world’s favourite Christie is underway. I picked the last, posthumously published, Miss Marple mystery, Sleeping Murder, but intend to re-read my way through her 80-plus other novels to check out the opposition before the winner is announced in September.

The 10th anniversary edition of Kate Mosse’s ‘Labyrinth’ (Orion) is out now

Margaret Drabble, novelist

I’ll be reading Owen Sheers’s new novel, I Saw a Man, despite the extremely boring and irrelevant discussions about genre fiction that are accompanying its publication. It’s said to be a page-turner, but no harm in that, and he has an excellent track record in other fields, so I’m looking forward to it. I read Ishiguro’s Buried Giant as soon as it came out, and although I don’t read much fantasy fiction, I loved his ogres as much as he does and felt very sorry for them. I can see the genre problem, though – I wouldn’t have read this book had it not been by him. And, for intellectual ballast, I shall catch up with Helen Small’s The Value of the Humanities, a book which we shall be needing as the new government revamps its education policies. She always has fine, balanced and persuasive arguments, and how we need them now.

Margaret Drabble’s most recent novel is ‘The Pure Gold Baby’ (Canongate)

Helen Dunmore, novelist

I’ve spent many months reading new fiction as a judge for the Baileys Women’s Prize for Fiction, and this summer I’m reading poetry, preferably that which is at least 200 years old. I want to immerse myself in Coleridge’s conversation poems and to re-read Richard Holmes’s superb, inspiring two-volume biography of Coleridge (Early Visions and Darker Reflections).

Holmes captures the brilliance, wit, melancholy and compelling presence of Coleridge, and follows his “living footsteps” from the West Country to the Lake District, Italy, Malta ... and finally to Highgate. In his introduction to Early Visions, Holmes quotes Leigh Hunt’s description of Coleridge as “a mighty intellect put upon a sensual body ... very metaphysical and very corporeal”. Holmes himself calls the poet “a hero for a self-questioning age” and Coleridge is surely that. The greatness of his imaginative gifts makes the thought of a summer in his company a very beguiling one.

Helen’s Dunmore’s most recent novel is ‘The Lie’ (Hutchinson)

Elleke Boehmer, Man Booker International 2015 judge and novelist

I’ve spent the past two years reading some incredibly exciting novels in translation, originally written in languages ranging from Arabic to Afrikaans. Stimulating as this has been, I’m looking forward to spending my summer getting reacquainted with all the new, interesting fiction in English from around the world that has been published in the interim. I’m imagining the experience will feel a little like sinking back into the curves of a familiar but recently unused deckchair.

Top of my list is the work of the fascinating Australian novelist Elizabeth Harrower, who published five novels in the 1950s and 1960s, and then fell silent, feeling (mistakenly) that her last book, In Certain Circles, was a “dead novel”. Text Publishing in Australia has just reissued all her work and I’m picking in particular The Watch Tower, the story of two sisters and one controlling man. We International Man Booker judges were particularly proud to include four out of 10 women writers on our shortlist and this interest in writing by women is clearly carrying over into my summer reading, as is my interest in Irish writing. The Irish novel always sets great models of spellbinding modern story-telling and this summer I’m looking forward to Anne Enright’s The Green Road, another intriguing story of a family reunion from this breathtaking author, and also Belinda McKeon’s first novel, Tender, a first love story, which promises insights into that singular state of compulsive feeling no writer can leave alone for very long.

Elleke Boehmer’s ‘Shouting in the Dark’ is out in July (Sandstone Press)

Antony Beevor historian

As I will be travelling a great deal because of my new book I will be relying on my Kindle to work my way through the collected works of Saul Bellow, which I shamefully admit I have never read. As for forthcoming hardbacks, I am longing to read Dominic Lieven’s Towards the Flame – Empire War and the End of Tsarist Russia. Lieven is not just one of the greatest historians on Russia, but is also a great writer. I thoroughly enjoyed his Russia Against Napoleon, which was also superbly researched. This new book looks as if it will give us another important perspective on the origins of the First World War and thus its consequences too.

The other book that I will be reading this summer, although it is not published until September, is Timothy Snyder’s Black Earth. Snyder, who wrote the magnificent and important Bloodlands, is now focusing on the first stage of the Holocaust, what Vasily Grossman called the “Shoah by bullets” (as opposed to the subsequent “Shoah by gas”). Snyder re-examines the assumption that the Holocaust was unique, and this should once again provoke a very useful and healthy debate.

Antony Beevor’s new book is ‘Ardennes 1944: Hitler’s Last Gamble’ (Viking)

Sarah Hall, novelist

Since discovering Kent Haruf – I was lucky enough to be on the Folio prize panel that shortlisted Benediction – I’ve been in awe of his humanity and subtle power as a writer. I seldom pre-order books but have been waiting for his final piece of work. Our Souls at Night returns to the fictitious district of Holt, and the lives of its residents. Though Haruf’s language is often plain-spoken and his subjects quotidian, there is enormous resonance and meaning to his work. The book might be slender but I’m certain it will not feel small.

The Thrilling Adventures of Lovelace and Babbage by Sydney Padua is a stylish, funny graphic novel featuring Ada Lovelace, estranged daughter of Lord Byron, and co-programmer, had it ever been built, of the “mathematical engine”. Playful, earnest, and beautifully drawn, the book cuts a swathe through early computing theory, explores Ada’s relationship with Charles Babbage, and brings to the fore one of the unsung heroines of science.

Sarah Hall’s latest novel is ‘The Wolf Border’ (Harper)

Natalie Haynes, writer and classicist

This summer, I plan to read Keeping an Eye Open. Julian Barnes, writing beautifully about art? Hard not to see this being my book of the year. I’m also looking forward to Kate Atkinson’s A God in Ruins. I loved Life After Life: just for wrangling that structure, she deserved every plaudit going. And on top of the cleverness, it packed a huge emotional punch. So I can’t wait to dive back into her world. And finally, Finders Keepers: I’m sometimes too squeamish for Stephen King, but Mr Mercedes was a terrific thriller, and now there’s a sequel. I squeak with glee.

Natalie Haynes’s recent novel is ‘The Amber Fury’ (Corvus)

Patrick Gale, novelist

A great perk of helping run the autumnal North Cornwall Book Festival is the excuse to devote deckchair time to the latest books from our visiting writers. So I’ll be re-reading Patricia Duncker’s Sophie and the Sibyl, her mischievously subversive romance in which George Eliot is the other woman. I’ll also be devouring Miranda Carter’s latest Raj-set thriller, The Infidel Stain, and the no less exotic Deeper than Indigo, a work of obsessive stalking from intrepid traveller and textile specialist, Jenny Balfour-Paul, who claims to have fallen deeply in love with its young subject after she stumbled on his letters home from the far East in a library.

I’ve not yet nabbed him for the festival, but I will sleep with almost anyone to obtain an advance copy of Andrew Miller’s new novel, The Crossing. I’ve avoided reading anything about it, trusting simply in my faith that, like Colm Tóibín, he can write no wrong.

Patrick Gale’s latest novel is ‘A Place Called Winter’ (Headline)

Tanya Byron, psychologist and broadcaster

Of the three books I’m really looking forward to reading this summer two are actually sequels that I have been waiting for from two of my favourite writers.

The first sequel is Early Warning by the incomparable Jane Smiley. It is the second in the Last Hundred Years trilogy. I loved the first, Some Luck, as I’ve loved all her books. The second is Kate Atkinson’s sequel to Life after Life. I may have to re-read that to reacquaint myself with Ursula’s many alternative lives before starting A God in Ruins, which focuses on Ursula’s younger brother Teddy.

The third book I’m looking forward to reading is Nick Hornby’s latest, Funny Girl, which I think will bring back memories of going to see my father directing at BBC TV studios during the 1970s.

I’m also beyond excited about publication of Harper Lee’s prequel to To Kill a Mockingbird, a book I fell in love with when I studied it for A-level in 1985.

Finally I will re-read Emma by Jane Austen this summer as I do on holiday every year – a brilliant, funny book about a young woman, born before her time, who was honest, brilliant and flawed.

Tanya Byron’s book ‘The Skeleton Cupboard’ is out now (Macmillan)

Nicola Barker, novelist

My pal Jon Savage strongly recommended that I read Andrew Matheson’s debauched punk memoir Sick On You and you’re not going to get a better recommendation than that. Matheson’s book details the highs, but mainly the lows, of the Hollywood Brats – Britain’s “great lost punk band” – in the shark-infested shallows of the 1970s London music scene.

During a recent lunch with a beloved former editor I was ashamed to admit that I’ve never actually read CS Lewis’s Surprised By Joy. I naturally intend to rectify that crass omission very soon.

And because Ted Hughes’s Crow is my favourite book of all time, the advent of publishing wunderkind Max Porter’s tribute to Hughes’s savage classic (let’s face it, an undertaking of truly gonzoid precocity) in his debut book Grief is the Thing With Feathers has me sitting up and taking notice. Will it be a revelation? Will it be a travesty? Ask me in the autumn.

Nicola Barker’s latest novel is ‘In The Approaches’ (Fouth Estate)

Dom Joly, comedian and journalist

Seven Days in Syria by Janine di Giovanni – a book that recounts the real human stories of this heart-breaking conflict: how people live, how they endure and how they find the strength to carry on. Syria is so close to my heart as, growing up in Lebanon, we would embark on regular family expeditions into that most beautiful of countries.

Also The Girl with Seven Names: A North Korean Defector’s Tale by Hyeonseo Lee – she fled at 17 and lived 12 years in China before mounting a daring rescue of her mother and brother. She tells her story of escape and subsequent survival. I saw a documentary on this woman and long to read her book. I visited North Korea for 10 days a couple of years ago while writing a travel book. It’s still the most unbelievably surreal destination I have ever travelled to – like some totalitarian theme park.

‘Here Comes the Clown: My Stumble Through Show Business’ by Dom Joly is out now (Simon & Schuster)

Patricia Duncker, novelist

When I was a young adult I read Great Expectations and Oliver Twist for advice on how to face the world. I frightened myself into fits. Now I have begun my initiation into modern YA – young adult fiction. Dystopias are alarmingly popular. Louise O’Neill’s Only Ever Yours is a savage school story about brainwashed fembots, women designed to belong to men either as companions or as concubines, with a “termination date” of 40. The girls are obsessed with social media and trash TV. Read it first, then give it to your pubescent daughter.

Paul Magrs’s Lost on Mars is a wonderfully written sci-fi adventure about a pioneer family on the desert plains of the red planet, a terrifying, inhospitable world of massive dust storms. Then the disappearances begin. Grandma is taken and all that is left is her cybernetic leg. Completely irresistible.

Patricia Duncker’s new novel is ‘Sophie and the Sibyl’ (Bloomsbury)

Alexandra Pringle Editor-in-Chief, Bloomsbury

This summer I want to briefly forget Britain of 2015 and travel to other times and other places: two favourite authors who write of favourite countries. First to India. Rumer Godden is too easily written off as a light read, but she is an acute and sensuous writer, and her portrayals of eccentric young girls in foreign lands are a particular delight. I look forward to losing myself in one of hers I’ve not yet read, The Peacock Spring, a story of teenage girls and their diplomat father in New Delhi of the 1950s.

Then to Italy. There is nothing better than finding an author whose wonderful characters reappear in book after book. Barbara Trapido (in Brother of the More Famous Jack and four subsequent novels) and Elizabeth Jane Howard (in The Cazalet Chronicles) are supreme examples of authors whose series of novels I could read over and over again. Last year I discovered the first of Elsa Ferrante’s stunning Neopolitan novels and this summer I can’t wait to read the second and third – The Story of a New Name and Those Who Leave and Those Who Stay, when I will meet Lila and Elena again and follow their lives in Naples of the 1960s and 1970s. Then I will be ready for the fourth, The Story of the Lost Child, due to be published in the UK this autumn.

Aamer Hussein, short-story writer and critic

I’ve been reading the Argentinian fabulist Silvina Ocampo’s dark, quirky short fictions for well over a decade, but haven’t been able to recommend her work to friends who couldn’t read Spanish. Now Those Were Their Faces finally makes a comprehensive selection of her stories, written between the Thirties and the Eighties, available to an Anglophone audience. I’m also enjoying the enigmatic stories of the Swiss Modernist Regina Ullman in The Country Road, first published in 1921 and now exquisitely translated from the German by Kurt Beals.

I’ve just discovered the complex, beautiful work of Indian poet Ranjit Hoskote in Central Time, and am slowly reading The Buried Giant by Kazuo Ishiguro, which is so moving I can’t bear to rush through it.

Aamer Hussein’s latest short story collection is ‘Bridges and other stories’ (HarperCollins India)

Xiaolu Guo, novelist

If you are a Tory voter, would you grab a copy of Hilary Mantel’s The Assassination of Margaret Thatcher this summer for your beach holiday reading? I hope you would. Exactly because of the irritating title and subject. I recommend this thinnest book ever written by Mantel, not because the author has collected two Man Bookers, and has garnered massive success with her television adaptations, but because of the current political atmosphere in Britain, especially in England, whose government is possessed by the ghost of the Iron Lady.

The 10 short stories here are a revelation about who Mantel really is, rather than a mere display of great literary craft. This collection offers a much wider range of topics than any Mantel’s other work. Definitely worth reading under the decaying Mediterranean sun.

Xiaolu Guo’s new novel is ‘I Am China’ (Chatto & Windus). In 2013 she was named one of Granta’s Best of Young British Novelists

Magnus Mills, novelist

On a summer’s day in 1215 a beleaguered English monarch met a group of disgruntled barons in a meadow by the river Thames. Reluctantly he set his seal to a “Great Charter” and their disgruntlement vanished at a stroke. Well that’s one version of the story anyway. The truth, of course, was rather more complicated, and the enthusiastic historian Dan Jones provides a series of insights and explanations in his highly presentable book, Magna Carta: the Making and Legacy of the Great Charter. The vast array of illustrations range from medieval manuscripts and frescos to 18th century engravings and “look and learn”-style colour posters. There are detailed miniature portraits of the main players, and we quickly discover that, although John was “an awful king”, he was surrounded on all sides by thugs, self-seekers and turncoats.

Magnus Mills’s latest novel is ‘The Field of the Cloth of Gold’ (Bloomsbury)

Boyd Tonkin, 'Independent’ writer

This summer, go to Iceland. With The Heart of Man, Jon Kalman Stefansson completes an extraordinary trilogy of novels set a century ago on the bitterly beautiful coast of his country’s West Fjords. Wonderfully translated by Philip Roughton, the sequence – which begins with Heaven and Hell and continues with The Sorrow of Angels – folds a spectacular epic of nature and society into a rite-of-passage tale. Another compelling account of the growth of a creative mind flows through Philip Glass’s memoir Words Without Music. From Baltimore to Buddhism, bebop to Beckett, the most versatile of living composers scores the soundtrack of his life with charm, humility and insight.

I came late to the cult of Lawrence Osborne, having been deterred by frothy plaudits from literary lads. But Hunters in the Dark, in which an archetypal Brit abroad in Cambodia drops into a darker world than he could imagine, escapes the curse of Graham Greene pastiche. It reveals a voice and vision several cuts above mere macho orientalism.

Jamie Byng CEO, Canongate Books

I often come to books early or late but don’t care either way when I read something extraordinary. Kazuo Ishiguro’s The Buried Giant was one of my reading highlights of 2014 but it continues to haunt me and I would be surprised if a more original, subtle or memorable novel is published this year. Emily St John Mandel’s Station Eleven classic from last year is the last novel I read and, like The Buried Giant, is another modern masterpiece that I am certain people will be reading for decades to come and will improve with age. Both these books reminded me of Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451, one of my favourite novels of the 20th century.

The piece of non-fiction that I would recommend to anyone who in interested in the mind’s complex relationship to the body is Gavin Francis’s Adventures in Human Being, another brilliantly original and highly engaging book that takes you on a journey that is both familiar and unfamiliar, a book that marries both the physical and metaphysical with such imaginative wit and eloquence.

I would happily read any of these three books again and would be surprised if I didn’t.

Christopher MacLehose publisher, MacLehose Press

Schubert’s Winter Journey by Ian Bostridge is an obsessive (by the author’s admission) exploration of the origins and creation and performance of Schubert’s cycle of 24 songs for voice and piano. The cycle is a masterpiece, the author is an exceptional Lieder interpreter and his book comes close to matching WG Sebald’s The Rings of Saturn for the sheer generosity and exhilaration of its scholarship. I am delighted to have found this book in Robert Topping’s bookshop close to Ely Cathedral.

Ellen Elias-Bursac’s subtitle “Working in a Tug of War” would be more digestible as a title than her Translating Evidence and Interpreting Testimony at a War Crimes Tribunal. The book is limitlessly admirable for its surgical analysis of the work of (more than 100 at any one time) interpreters and translators at the trials at the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia. I have read half of the book and will read it all again. It is hard to imagine a more rigorous or more absorbing book on the work of translation involved in the administering of justice in a series of trials that will have lasted more than 22 years when they come to an end next year. The author was for six years one of the translators.

Kate Hamer, novelist

As a debut novelist I have an instinctive empathy for the clutch of debuts coming out this summer – Eileen by Ottessa Moshfegh looks wonderfully creepy and affecting. Jonathan Galassi has had a long career in publishing, which I imagine makes the publication of his debut Muse even more nervewracking. It looks charming – a wry homage to his industry revolving around the bitter rivalry between two publishing houses.

I’ll also be diving into Alice Hoffman’s The Marriage of Opposites, which pretty much earns that chestnut title of “must read” as does Judy Blume’s In the Unlikely Event. The recently published Adventures in Human Being, has also caught my eye. Published in association with the Wellcome Trust, Gavin Francis takes us on a journey through the body from “the ribbed surface of the brain to the secret workings of the heart and womb”. Fascinating stuff.

Kate Hamer’s novel is ‘The Girl in the Red Coat’ (Faber & Faber)

Aminatta Forna, novelist

“It was a catastrophe, when they shot the President and machine-gunned the Congress and the army declared a state of emergency. They blamed it on the Islamic fanatics at the time.” Exactly 30 years ago and long before we had heard the words “war on terror” or “clash of civilisations” Margaret Atwood published the extraordinarily prescient The Handmaid’s Tale. Read in the light of the assault on women’s abortion rights in America, to the horrors of Islamic State, her depiction of life for women in a theocratic American state makes chilling reading. If you read one book published this year, then you might make it Teaching Plato in Palestine, Philosophy in a Divided World. Carlos Frankael’s account of discussing classical and medieval philosophy is part intellectual travelogue, part journey into the minds of others, and often into the minds of those who are “othered”. From devout Muslims to lapsed Hassidic Jews to the descendants of the Iroquois warriors in Canada, Frankael tests their convictions and his own.

With the centennial year of Jack London’s death approaching, if you haven’t read Call of the Wild, White Fang or London’s masterful short story “To Light a Fire”, go buy yourself a copy. London’s extraordinary vision of the “white silence”, the savage beauty of the wilderness, would help pass the Wilderness Act nearly 50 years after his death, leading to the protection of nine million acres of federal land.

Aminatta Forna’s latest novel is ‘The Hired Man’ (Bloomsbury)

Nick Barley, director: Edinburgh International Book Festival

Alongside Anne Enright’s exceptionally good The Green Road, two other Irish novels are particularly worth a read this summer and both are partly set against the backdrop of that Celtic Tiger moment in Ireland’s recent past. I read a proof copy of Belinda McKeon’s deeply affecting novel Tender far too quickly and can’t wait to take longer over it when I’ve got more time to get lost in the wonderful depths of the relationship it describes. The raw, tragicomic humour in Paul Murray’s last novel, Skippy Dies, made it one of the most memorable books of 2010, and his latest, The Mark and the Void, is just as funny, though perhaps with an even deeper sense of alienation at its heart. Meanwhile the new book of poems by Don Paterson also contains some sparkling comic moments. He’s spent the past three years writing sonnets and, far from cramping his style, the discipline imposed by the sonnet form seems to suit him. Oh, and I can’t wait to read Tessa Hadley’s The Past: I’m sure it will be a bit special.

Joanna Rakoff, memoirist and novelist

I’ve been saving new books from two of my favourite writers, Meghan Daum and Christine Sneed, for the summer, and I’m near-drooling at the thought of turning to them, after a year heavy with obligation reading.

Daum’s latest, The Unspeakable, is a collection of essays, roughly organised around subjects that are difficult to broach, even with oneself. The excerpt published in The New Yorker, about her decision not to have children – and, instead, to mentor a troubled local kid – left me stunned and devastated for days, weeks, months.

Sneed, meanwhile, writes slyly funny, masterful comedies of manners utterly unlike anything else in American letters. Paris, He Said, her new novel, sounds almost too intriguingly Wharton-like to bear: A thirty-ish artist takes up her (much older, wealthy) boyfriend’s offer of a sojourn in Paris, free of rent and expenses. Does this make her his mistress? Can she paint under these retrograde conditions? Argh, I can’t wait.

Joanna Rakoff’s new novel, ‘A Fortunate Age’, is out on 18 June (Bloomsbury)

Raymond Tallis, philosopher and novelist

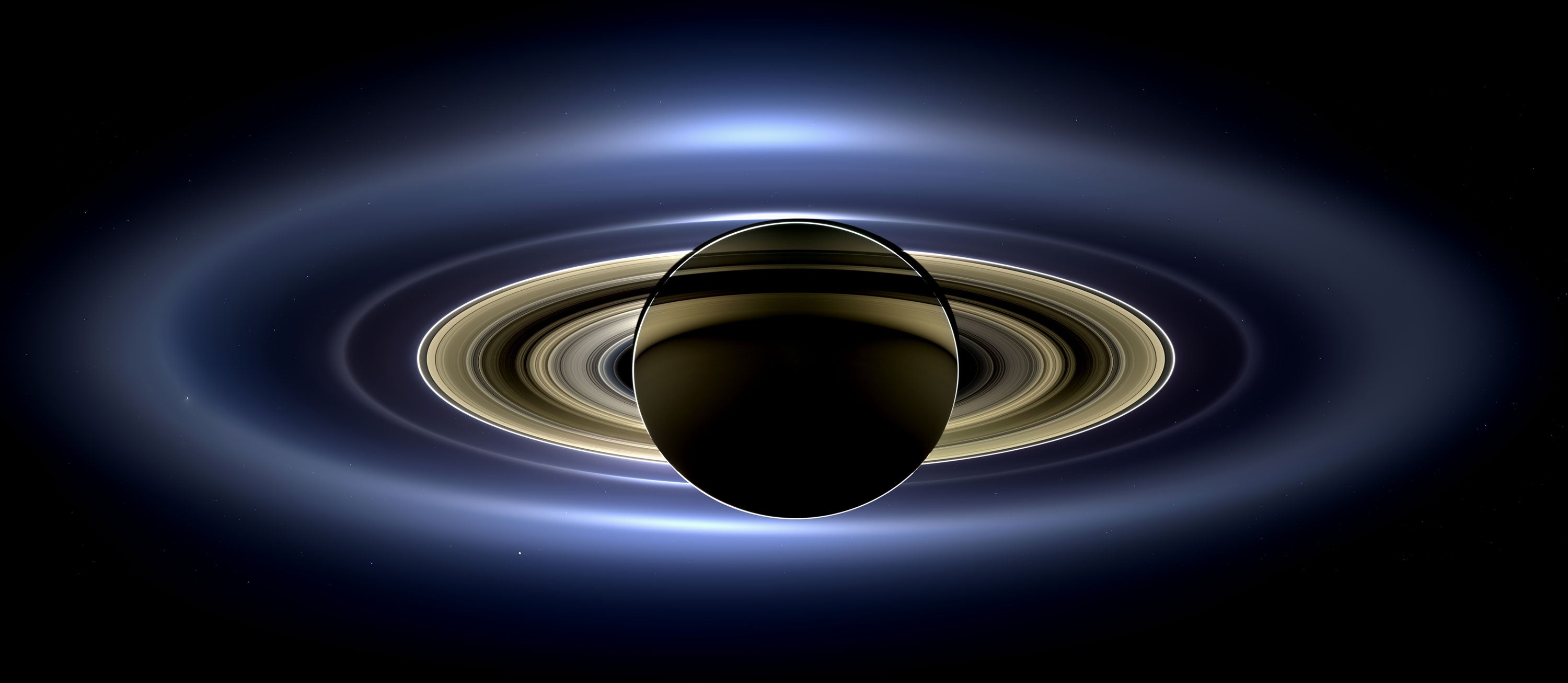

My Big Read this summer will be a re-read – The Singular Universe and the Reality of Time by Roberto Unger (a philosopher) and Lee Smolin (a leading physicist) published earlier this year. It is a magisterial assault on the bad metaphysics that has plagued contemporary cutting edge physics, resulting in, for example, the wildly fashionable (but strictly unscientific because untestable) idea that our universe is only one of an infinite number of parallel universes. If you are not persuaded that that the mathematical portrait of our world is the whole story, and our road to a Theory of Everything, Unger and Smolin will tell you why you should not be fazed by hubristic swivel-eyed physicists arguing the to the contrary. What’s more there are no equations to spoil your time on the beach.

Raymond Tallis’s ‘The Black Mirror: Fragments of an Obituary for Life’ (Atlantic) is published by in July

Sjón, author and former collaborator with Björk

As my companions on my excursions north and south this summer I have chosen three books that span genre and geography. The first is Caitríon O’Reilly’s poetry collection Geis. I first came across her poetry in The Sea Cabinet, a book that has the beauty and strength of a blue whale in its reach for the depths of experience and celebration of language as if it were oxygen. Geis (meaning “taboo” in Irish mythology) promises more sharp observations of nature both human and not, plus it features a poem called “Iceland”.

The second book is also about human/nature interaction, Fredrik Sjöberg’s warm, witty and wise The Fly Trap. In it Sjöberg tells two stories from the world of entomology. One is about his own humble hoverfly collecting on a small island in the Swedish archipelago, the other follows the life of René Malaise, inventor of the world’s best fly trap, adventurer and art connossieur. There is certainly no need to be a hoverfly collector to enjoy it but The Fly Trap might turn you into one.

Coming from a country that is repeatedly touted as the most book-loving place on Earth I am in constant awe of the literary powerhouse that is Nigeria. Recently I have enjoyed books by Chika Unigwe, Helen Oyeyemi and Helon Habila, to name but few, so I have high expectations for my third summer book, Chigozie Obioma’s debut novel The Fishermen.

Sjón’s latest novel is ‘The Boy Who Never Was’ (Sceptre)

Polly Samson, novelist

Everything Elena Ferrante. I have just read all seven novels, gobbled them up, one straight after the other. Her three stand-alones: Troubling Love, The Lost Daughter and Days of Abandonment are all extraordinary, I have never read the internal life of women described with such blistering authenticity.

The Neopolitan novels are best saved for when there’s time for an unbroken binge. There’s a neighbourhood, a slum brutally ruled by Camorrists, politics and revolution, earthquakes and murders and at its heart two fascinating women. Mount Vesuvius is a fitting backdrop to the two women’s intense and ambiguous friendship and to the choices they face as Italy erupts into modernity. The writing is fearless, immersive, recounts frankly all human experience, emphatically that which seems unsayable. With the fourth and final book (The Story of the Lost Child), I predict that #FerranteFever will become a #FerrantePandemic by summer’s end.

Amanda Craig, author and children’s book critic

Sarah Garland’s Eddie’s Tent (for children aged four to six) is warm fun for seaside holidays, part of a charming child-centred series. It shows a family enjoying a camping holiday – putting up a tent, fishing, having a BBQ, losing and finding the dog. The information is as sensible as the story is sweet.

Emma Carroll’s In Darkling Wood (ages seven to nine) takes the fake fairy photographs that fooled Sherlock Holmes’s creator and asks: “What if the fairies were real?” Alice’s brother is desperately ill; her grandmother wants to cut down an ancient wood. How can both be saved? Absorbing, sensitive and genuinely magical in feel.

Robin Stevens’s Arsenic for Tea (ages eight to 12) has her 1930s schoolgirl detectives solve a murder mystery committed at a country house-party. Witty, clever and gently satirical of upper-class life, it’s Agatha Christie crossed with Angela Brazil. First Class Murder, set on the Orient Express, follows in July.

Quirky, touching and very funny, Andrew Norriss’s superb Jessica’s Ghost (ages nine to 12), is about a friendless boy who can talk to a ghost. An exceptionally funny book about depression and suicide, it may encourage those who hate school, and life, to give it another try. Paul Magrs’s Lost On Mars is about Martian settlers being Disappeared by Martians. Funny, scary, and like Ray Bradbury crossed with Laura Ingalls Wilder, it will appeal to boys and Dr Who fans.

My final recommendation isn’t out till September, but is the most exciting new children’s novel for a decade: Katherine Rundell’s The Wolf Wilder. She is a master story-teller in the Philip Pullman category. Set in 1915 Russia, it’s about a girl who re-wilds wolves – until the Tsar’s soldiers are commanded to shoot them.

Amanda Craig’s last novel was ‘Hearts and Minds’ (Abacus)

Laline Paull, novelist

I’m really looking forward to reading Sarah Hall’s The Wolf Border for two main reasons: her elegant visceral prose, plus the fascinating and controversial subject of re-wilding of former apex predators. With many threatened or endangered species – the wolf, the lynx, many birds of prey – we witness the natural world so thoroughly dominated, so cowed, that we must now fetishise the very animals we once most feared, in order to “ensure diversity”. These apex predators have also become the mirror in which a most rapacious creature looks back at us, in the form of our own cultured, industrialised face.

I’m also very much looking forward to reading respected journalist John Sweeney’s debut novel, Elephant Moon, based on the true story of how in World War II, a tribe of 53 Burmese elephants helped guide a group of mixed-race orphans through the jungle to safety in India.

Laline Paull’s debut novel, ‘The Bees’ (Fourth Estate), was shortlisted for the 2015 Baileys Women’s Prize for Fiction

Neel Mukherjee, novelist

Although Paul Murray is a friend, The Mark and the Void is so sensationally good that it would be wrong not to mention it. It takes the global financial crisis by its throat and shakes it into giving birth to a wild, intelligent, angry, witty, uproariously funny, devastating novel. Ruth Ware’s first novel for adults, In a Dark, Dark Wood, is going to be, without any doubt, this year’s hottest crime novel. I challenge anyone not to finish this book on toxic female friendships in one sitting. The South African writer SJ Naudé announces himself as a major talent in international literature with his first collection of stories, The Alphabet of Birds. Note his name – you’ll be coming across it frequently in years to come. Patrick Gale’s A Place Called Winter is, as you would expect from him, gripping, immensely moving, and glitchlessly written.

Neel Mukherjee’s ‘The Lives of Others’ (Chatto & Windus) was shortlisted for the 2014 Man Booker prize

Jonny Geller, joint CEO of literary agency Curtis Brown

I’m really looking forward to reading Anthony Doerr’s All the Light We Cannot See. Sounds like it has the full package – epic, lyrical, narrative led and with a beating heart. I want to read A Little Life by Hanya Yanagihara.

I have seen such overwhelming responses to it in proof form on Twitter that I feel confident it will deliver. I will nab a proof from my colleague of the new Jojo Moyes (out in September). My embarrassing confession – I will read The Master and Margherita by Mikhail Bulgakov – a book I thought I had read at university but realise now that was a lie.

Joan Bakewell, author

Holidays are a time out: and my choices are about time. Ali Smith’s win of the Bailey Prize is no surprise: her way with time and with words has long held us breathless at her daring and originality. How to Be Both tells two tales one after the other… but which one comes first? If you buy it on Kindle you get it in both directions. I read it twice.

One tale tells of the 15th-century painter Francesco del Cossa, whose work adorns a grand palazzo in Ferrara, and his challenge to the prince who employs him. The other tells of present-day Georgia, who is mourning the death of her mother, a cartoonist of outspoken views with whom she had visited the frescos in Ferrara. The interplay of ideas, of wordplay, and time-lapse is brilliantly done: Smith also finds space for intriguing gender fluidity, and Georgia’s own biography of del Cossa. The whole is like some brilliant philosophical conundrum about life and time and loss and art. Yet it has the deft touch of someone steeped in literature (Woolf’s Orlando finds an echo) and yet media savvy with the wit and jargon of social media.

Also worth many a repeat read is Clive James’s latest volume of poems: Sentenced to Life. James’s confrontation with his approaching death is nothing short of inspirational. Depressing? Melancholy rather: he is leaving a glittering life. But the very melancholy of its subject nourishes James’s pleasures in all that remains. Regret and loss certainly, but a glowing love of all things that survive; sunlight, trees, place he loved. His will to confront the inevitable, so lightly expressed, comforts all of us getting on in years.

Joan Bakewell’s most recent novel, ‘All the Nice Girls’, (Virago Press) is out now

Rachael Pells, ‘Independent’ writer

Summer reading for twenty-somethings means escapism, but I also want a novel I can relate to. For a beach read try We Don’t Know What We’re Doing, a collection of short stories by debut author Thomas Morris which are perfect for picking up intermittently – or for devouring in one sitting, as I did. Each 40- or 50-page story follows a new character from the same Welsh town, and, while not always cheerful, the stories are poignant and offer the underlying reassurance that nobody really knows what they’re doing in life, regardless of what stage they are at.

From a first glimpse, Alex Houston’s debut novel In My House looks promising as a psychological thriller to get hooked on, following the relationship of a trafficking victim and her unlikely rescuer.

In terms of non-fiction, I am desperate, if apprehensive, to read Ben Stewart’s Don’t Trust, Don’t Fear, Don’t Beg, which tells the story of the 30 activists seized during a Greenpeace mission in 2013.

I am feeling inspired by Madeleine Shaw’s cookbook Get the Glow, which offers a realistic six-week plan of action for health and happiness, and which most importantly doesn’t suggest that I cut out drinking or anything silly like that.

Additional reporting by Rachael Pells

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks