What's the meaning of 'chick-noir'? Week in Books

Next week, a literary salon will discuss the rise of the domestic thriller. Lucie Whitehouse, the novelist and one of three speakers at Bloomsbury’s event, has already called the genre by its other – not altogether uncontentious – name. “I’d define ‘chick noir’ as psychological thrillers that explore the fears and anxieties experienced by many women. They deal in the dark side of relationships, intimate danger, the idea that you can never really know your husband or partner...”

Writing about “the dark side of relationships” is surely not new. Joyce Carol Oates, for one, has been doing it in suspenseful ways for years. Neither is the idea that you can never really know your partner – we just have to draw our minds back to all that marital alienation and angst in John Updike’s Rabbit, Run series...

Yet Whitehouse has a point; the combined themes of marital dysfunction, psychological suspense and the complicated kind of sexual passions that fuel crimes, has led to a growth of a certain kind of story. And a certain kind of marketing. It was edgy when ASA Harrison’s debut, The Silent Wife, was posthumously published; it was commercialised by Gillian Flynn’s Gone Girl, and confirmed to be worthy of literary merit when AM Holmes won the Women’s Prize for May We Be Forgiven. None of these books would necessarily have been written as “chick noir”, but readers might see them as such. A flurry of books have certainly been marketed similarly since the success of these publications, many even with the familiar ‘embossed’ covers. I wonder if the panel next week will query the term ‘chick noir’ as many have done. The criticism is that it ringfences books artificially. It is the same kind of ringfencing that has led some to regard women’s fiction to be distinct from literary fiction: to think of Jane Austen’s novels, about love and relationships, as domestic fiction, and hail Philip Roth’s books, about love and relationships, as state-of-the-nation novels. Chick lit, the literary parent of chick noir, is used just as selectively. For instance, David Nicholls’ One Day, arguably classic chick-lit, wasn’t called any such thing. It’s a gendered debate, worthy of a panel discussion which defines – and justifies – its terms.

Can you judge a book by its velvet cover?

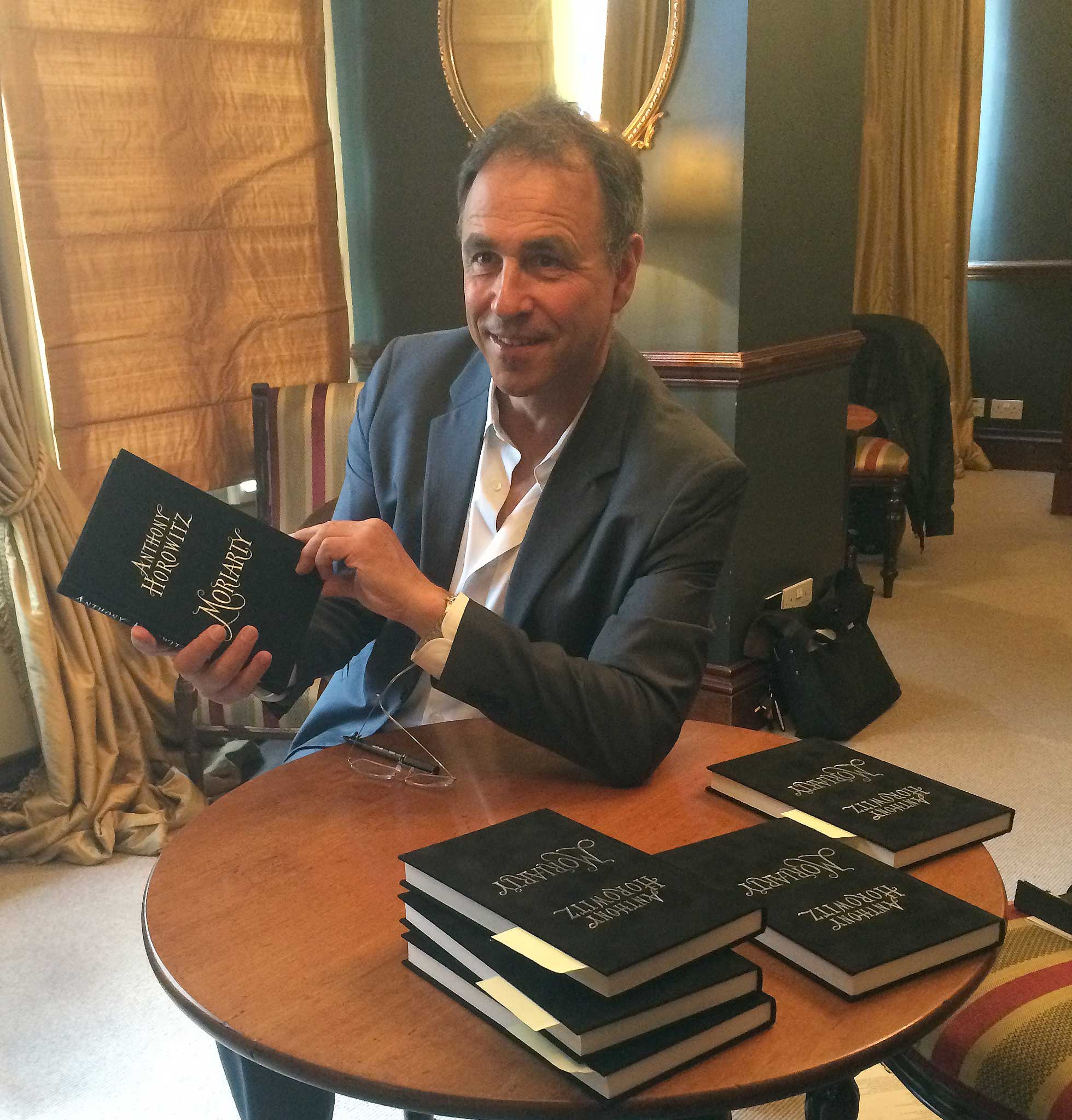

I was invited to attend a “proof” launch this week. It was the first time I’d gone to such a thing. It was to mark Anthony Horowitz’s new novel, Moriarty, which isn’t out until October, but if I turned up to a boutique hotel, I could, along with the select few, collect its “proof” – the provisional version of the book that reviewers are given ahead of the final fancy version with the hardback cover. Except this proof was very fancy indeed, made out of beautiful black velvet and silver lettering.

I was led to a queue so Horowitz could sign it for me. Mine was apparently proof No 33 out of 100 limited editions. Already, I was so glad I came. I was virtually handling gold-dust. The publishers didn’t want us to talk about the book. Surprise was of the element here. Of course, I thought, though I detected the drama of a soft-sell, or at least, it certainly felt like theatre. What’s the first thing you do when you’re told to keep quiet, because a literary bomb lies in between the velvet covers of the book you’re holding? Not that I would dream of breathing a word...

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks