Publishing Shakespeare: The men who made the Bard

It wasn’t enough to write the plays Shakespeare wrote; to make him world famous, publishers were needed, writes Andrew Murphy

Walk into any decent bookshop today in search of Shakespeare’s plays and you’re sure to find at least one. And even if you can’t find what you’re looking for on the bookshelves, there is always the internet, where a great variety of different complete works and editions are also available – almost all of them free of charge.

This, however, has not always been the case. In fact, in Shakespeare’s time, the texts were rather hard to find. The incredible access we have now to Shakespeare’s work is thanks to a handful of enterprising publishers who saw the earning potential of making the bard’s texts readily available to read.

The first publisher to take a chance on the plays was Thomas Millington in the late 1500s. Millngton was a small-scale operator who specialised in throwaway popular texts about murders and monsters and whose business was tucked away in an obscure corner of London. Millington issued editions of Shakespeare’s Titus Andronicus and of the second and third parts of the trilogy of plays that he wrote about King Henry VI. Despite the out-of-the-way location of his shop, Millington’s editions sold well and his success encouraged others to take a punt on some of the plays.

Preserve of the rich

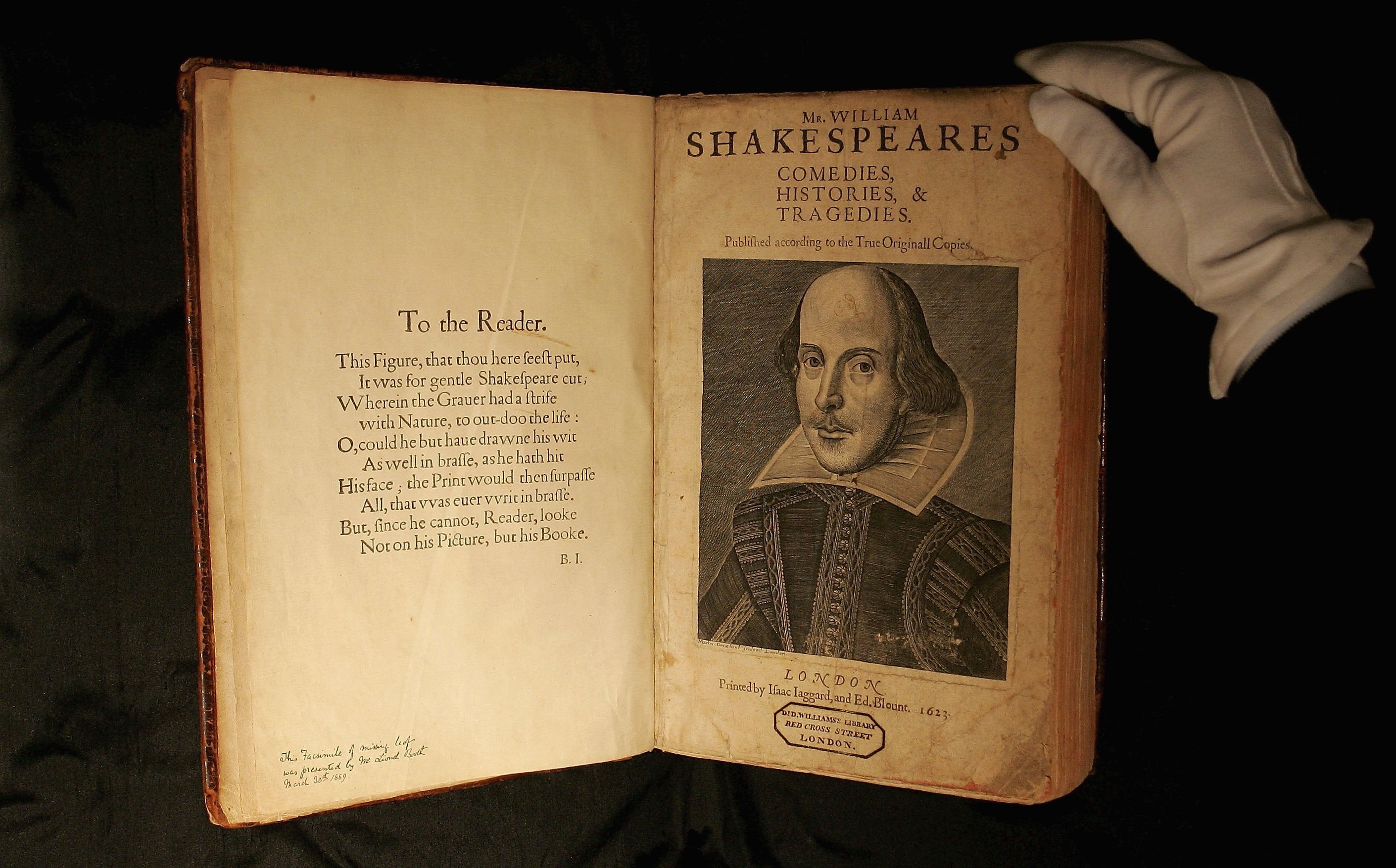

By 1623 – seven years after Shakespeare’s death – sales had been good enough for almost all of the plays to be published together in a collected edition – a volume conventionally known as the First Folio (folios were the largest-sized books). But this edition was very expensive, costing about £1 – the equivalent of almost nine days’ wages for a skilled craftsman. It was thus a luxury item that only the wealthy could afford. And it set the pattern that was followed for many decades, with Shakespeare’s plays remaining largely confined to an elite readership who had the funds to buy expensive editions.

The first person to try to break this pattern and open up access to Shakespeare was Robert Walker (circa 1709-61).

Walker had a lot in common with Millington in that he mostly published cheap, disposable, sensationalist texts. He also had a sideline in quack medicines, as he manufactured and sold “Daffy’s Elixir”, a concoction advertised as an effective cure for almost all known diseases.

In the mid-1730s, Walker waged a price war with the London publishing establishment, driving the cost of individual play editions down to just one penny each. This led to a significant expansion of Shakespeare’s readership and, consequently, to a much greater demand for performances of Shakespeare’s plays in the 18th century.

Shakespeare for all

In the following century, another out-of-the-way publisher, John Dicks, followed Walker’s example and lowered the price of access to Shakespeare even further.

Dicks came, himself, from a very humble background and was determined to make great literature available to the poorest sectors of British society. In the 1860s, he issued Shakespeare’s plays individually at the rate of two plays for a penny – half of Walker’s price more than a century previously.

Dicks then collected all of the plays into a single paperback volume which he offered for sale for just 12 pennies, the equivalent of less than a third of a penny per play – far and away the cheapest price ever for a complete Shakespeare. Dicks estimated that he sold almost a million copies of this book, making it the most successful Shakespeare edition that had ever been published.

Dicks can be said to have done more to popularise Shakespeare than any other publisher. But even his achievement has been surpassed in our own time. The key actor today is, again, a rather obscure figure: a computer programmer called Grady Ward, who created a digital edition of the plays in 1993. Ward made his files freely available to others and they became the basis for a wide range of free-to-access Shakespeare websites and apps. The chances are that if you’ve ever looked at a Shakespeare play online, you will have been looking at some version of Ward’s original files.

We have seen that John Dicks sold nearly a million copies of his shilling edition of Shakespeare. Figuring out how many people have made use of Ward’s text is a little harder. A possible guide may be the number of users of just one version of it: Eric Johnson’s Open Source Shakespeare. Between 2006 and 2020 this site attracted just short of 19 million distinct users. Given this level of traffic on just one site, it does not seem unreasonable to speculate that the combined number of users for all the various sites and apps may well be approaching 100 million.

In our own time, Shakespeare is a global phenomenon, freely available either in print form or online. But we should never forget the debt we owe to those who have helped to popularise his work over the centuries – the Millingtons, Walkers, Dickses and Wards – the unsung heroes who helped so much to make Shakespeare what he is today.

Andrew Murphy is 1867 professor of english at Trinity College Dublin. This article first appeared on The Conversation.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks