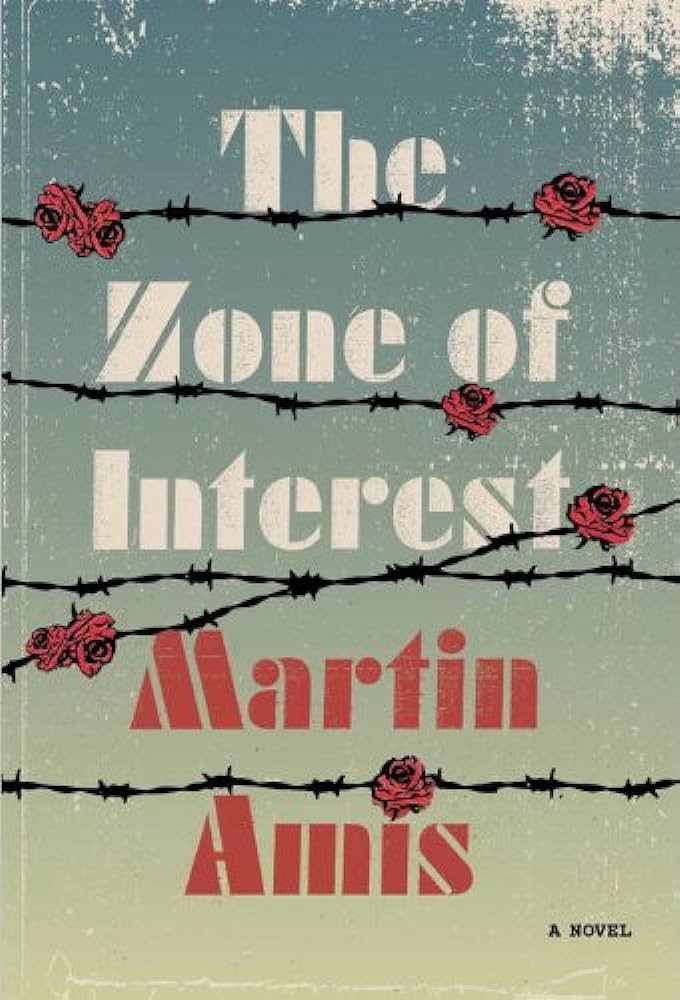

The Zone of Interest was Martin Amis’s greatest novel of the 21st century

Jonathan Glazer’s Oscar-nominated drama about the Holocaust is only loosely adapted from the late author’s 2014 novel, but it’s a work in which Amis deployed irony so savagely it can make you gasp, says John Self

The thing we’re most scared of, I think, is that we could be them. They were human beings,” says Jonathan Glazer of the central characters in The Zone of Interest. Released on Friday, his new film comes pre-packed with expectation, following a rapturous reception in Cannes last year and five Oscar nominations including Best Director and Best Picture – not to mention Glazer’s track record. (The Zone of Interest is only his fourth feature in 24 years.)

The film tells the story of an idyllic home life, and the greatest horror of the 20th century, side by side. The Zone of Interest – an exquisitely anonymous phrase – was the 40-square-kilometre area (15.5-square-mile) around the Auschwitz concentration camps designed by the Nazis to shield the camps from Allied attacks and from the outside world’s knowledge. The film is set in the home of real-life camp commandant Rudolf Hoss and his wife Hedwig (“We’re living as we dreamed we would,” she says) and their children within the Zone of Interest, following their mundane concerns, ambitions and frustrations, while the gas hisses and the smoke rises behind them. “We wanted to capture the contrast,” says Glazer, “between someone making a cup of tea and someone being murdered on the other side of the wall.”

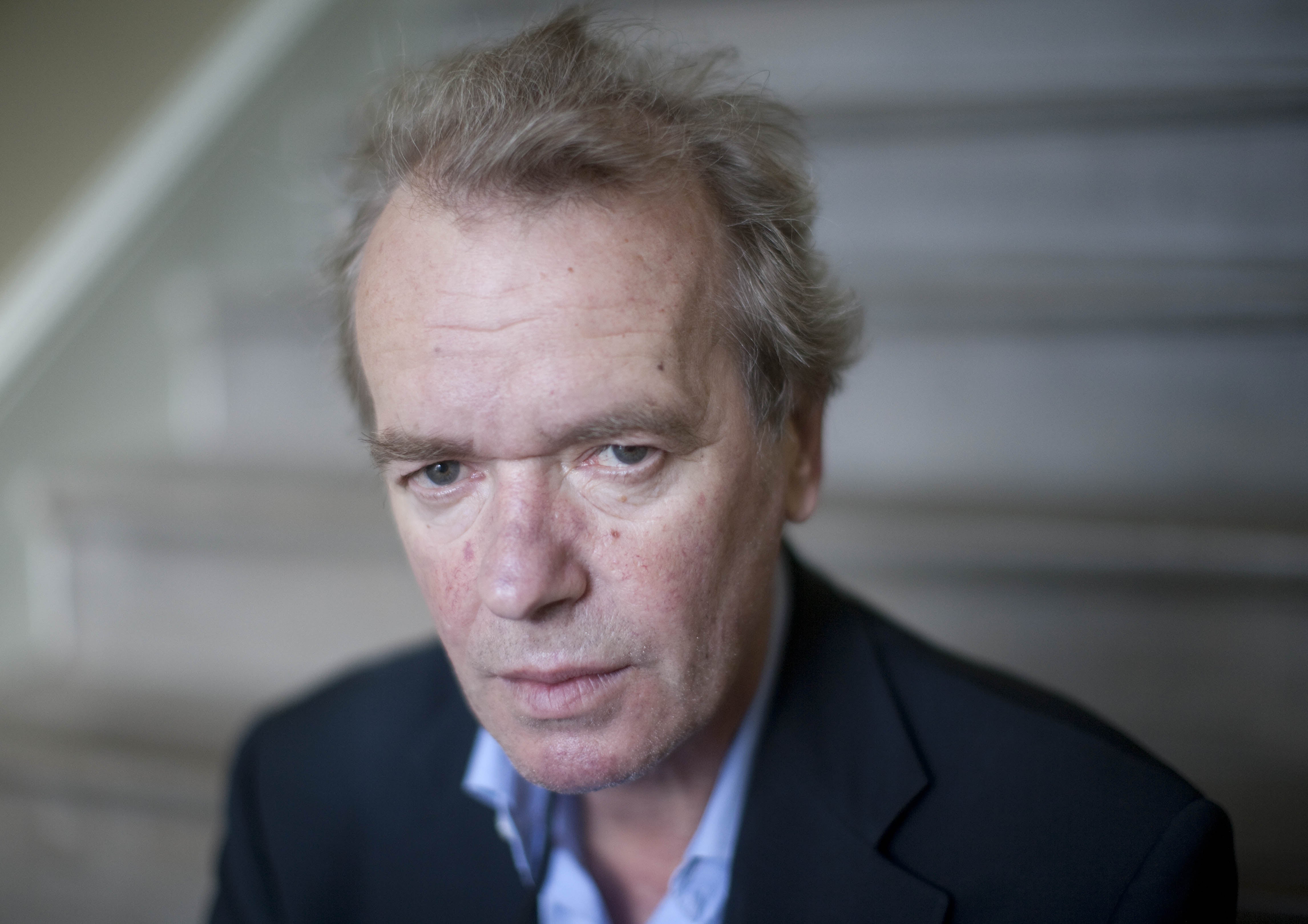

The film is a loose adaptation of the 2014 novel by Martin Amis, and when Amis died last year, the obituaries agreed that The Zone of Interest was a high point amid late work that was – put mildly – of variable quality. I will go further and say that it is his best novel of the 21st century. (I exclude from this reckoning his final book Inside Story, which was also very good but was not, whatever its subtitle, a novel.)

This might seem surprising. Amis was, after all, a comic writer at heart, attracted to big grotesque characters in satires of contemporary England, a writer who (in his own words) dealt in “banalities delivered with tremendous force”. So where did The Zone of Interest come from, and what made it so good?

The truth is that even as he made his name with comic masterpieces like Success (1978) and Money (1984), Amis was itching to move beyond what one critic called “mere brilliance” and tackle meatier matters. But topics came and went – nuclear weapons in Einstein’s Monsters (1987), the environmental catastrophe that provided the setting for London Fields (1989) – until he alighted on the most troubling subject of the century, the Holocaust, in Time’s Arrow (1991), which told the life story of a Nazi doctor in reverse.

The divide in Amis’s fiction from the highs of the 1980s and Nineties to the lows of the new millennium is stark. When he tried to recapture his early comic form, his novels of the 2000s delivered diminishing returns, from the messy Yellow Dog (2003) to the exhausting The Pregnant Widow (2010), and the lottery-lout farce Lionel Asbo (2012), with its toe-curling subtitle (“State of England”), was particularly unwise coming from a man who now lived in a Brooklyn brownstone.

What’s clear now is that Amis was becoming less interested in fiction, and more concerned with what really happened. His memoir Experience (2000) was universally acclaimed, and he followed it with a book on Stalin, Koba the Dread (2002). History, and the truth, were now inspiring his best work, and he said that the World Trade Centre attacks on September 11, 2001 meant that “all the writers on earth were reluctantly considering a change of occupation”. The essential triviality of making stuff up didn’t seem equal to our new challenging century.

His breakthrough came with House of Meetings (2006), his first good novel of the new era, which was about a love affair in Stalin’s gulags; then, finally, The Zone of Interest. In one sense he had been working through its theme since Time’s Arrow, where the Holocaust could only make sense in a world that ran backwards. In the afterword to that novel, Amis observed how the Nazis built roads that were “designed to conform to the landscape, harmoniously, like a garden path”.

It is the unexpected harmony of domestic life alongside the worst horror of all that is the subject of The Zone of Interest. Like the film, the novel puts at its centre the day-to-day lives of the Germans working at Auschwitz, but where Glazer focuses on Rudolf Hoss’s family, Amis’s book is multi-stranded. Hoss is fictionalised as Paul Doll, an uptight bureaucrat of a camp commandant and one of the book’s three narrators, whose only qualms when it comes to killing Europe’s Jews is whether he can build the third camp that’s deemed necessary to expand the scale of the slaughter. “This is going to be an absolute nightmare!” he cries. “No wonder my head is splitting!”

Doll’s wife Hannah is, in the eyes of the second narrator, “built on a stupendous scale: a vast enterprise of aesthetic coordination”: this narrator being Golo Thomsen, nephew of Martin Bormann, worker at the IG Farben rubber factory in the camp grounds, and a man with an eye on the boss’s wife. As his description of Hannah Doll suggests, he is a classic Amis giant in both style and character (note the lavish, but not quite loving, description of a woman).

The final narrator is the “infinitely disgusting, and infinitely sad” Szmul, one of the Sonderkommando: Jews who escaped death by working in the gas chambers harvesting valuables from other Jews. It is the lowest circle of hell. And so the story proceeds – Thomsen and Hannah Doll’s affair, Paul Doll’s angst at his workplace stress, Szmul’s downward spiral – but, where Glazer says “we stayed on one side of the wall”, the book goes into the camp.

The Zone of Interest succeeds because it deploys Amis’s tastes for grotesquerie to the most grotesque of settings, where explanations cannot be offered; the only approach to the inexplicable is to witness those who treated it as normal. And it is a perfect final work of fiction for Amis because it uses not his usual broad humour but instead savage irony, juxtaposing opposites as he did earlier in his career – then for bright comic effect, now for comedy so black it makes you gasp rather than laugh. “I never cease to marvel,” says Paul Doll about Szmul, “at the abyss of moral destitution to which certain human beings are willing to descend.” Irony and incompatible pairings have always driven Amis’s curiosity. This time he wrote about the bitterest irony of all – and he didn’t even have to make it up.

‘The Zone of Interest’ is out now in cinemas

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks