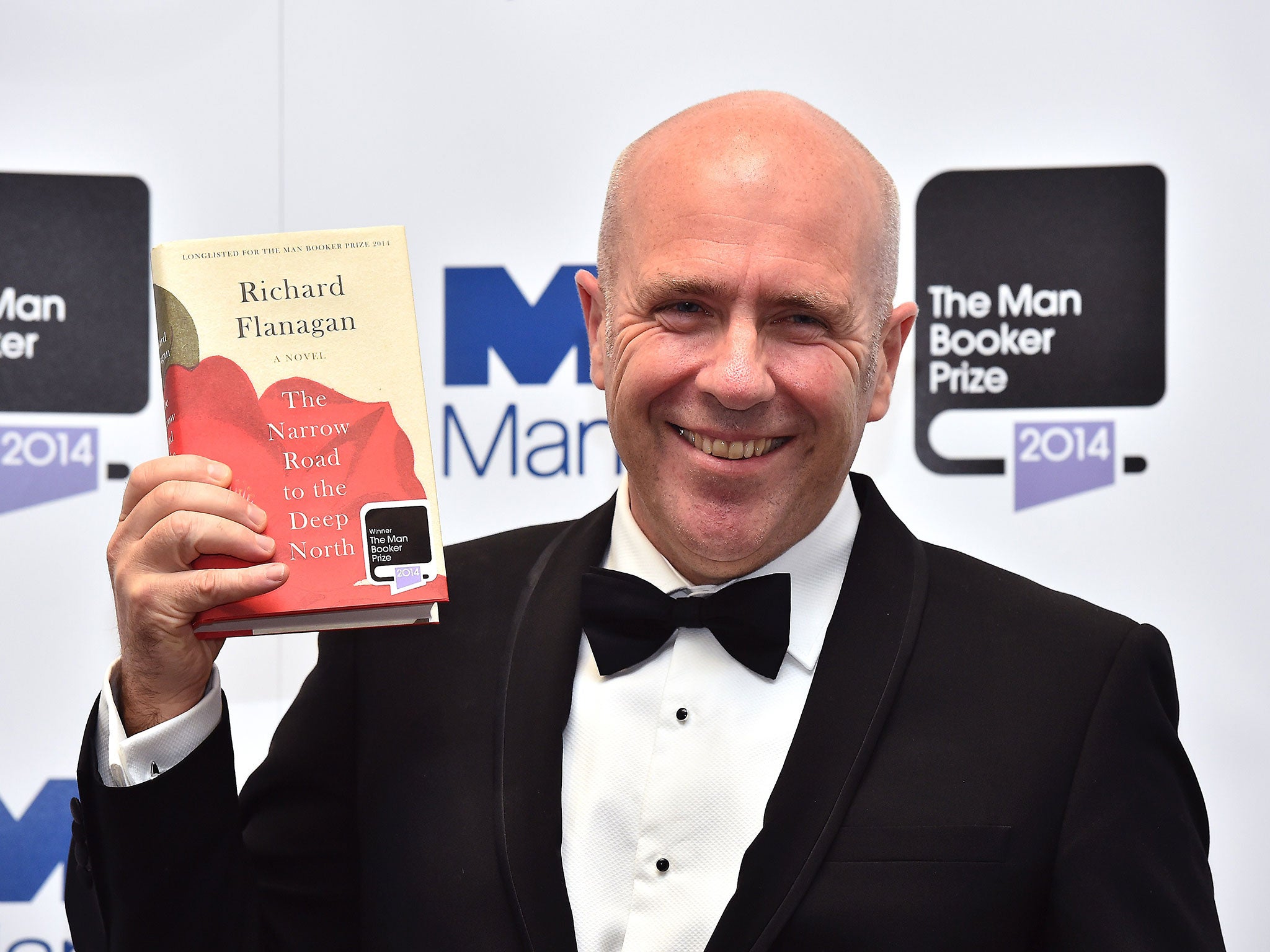

Man Booker Prize 2014: Richard Flanagan wins with The Narrow Road to the Deep North

Feared American takeover fails to materialise

Richard Flanagan was tonight awarded the Man Booker Prize for a Second World War novel about the Burma Death Railway; a story inspired by his father, who survived the railway but died the day the book was finished.

The Australian author won the most acclaimed prize in the British literary calendar for The Narrow Road to the Deep North, a book that “kicked the judges in the chest” and which is dedicated to his father Archie Flanagan, acknowledged as prisoner number 335.

Mr Flanagan, 53, hugged The Duchess of Cornwall as she handed him the award and a cheque for £50,000 at the ceremony in London’s Guildhall. The Tasmanian is acclaimed in his home country, but his profile is set to soar internationally after winning the prize.

He said: “I’m very grateful for this; it’s one of the greatest honours you can be accorded in the world of literature. I didn’t expect it. I was shocked to be on the longlist.” He revealed that the prize-money would allow him to go on writing. After finishing the book last year, he had considered quitting writing to look for work in mining.

AC Grayling, chair of the judges, said the “beauty of the writing” made the book stand out and went on to hail its “profoundly intelligent humanity. Some of the passages describing the experience of prisoners of war are excoriating”.

Man Booker 2014 shortlist

Show all 6Mr Flannagan’s sixth book is about the experiences of a fictional surgeon in a Japanese prisoner of war camp on the infamous Thailand-Burma railway. It takes its title from one of the most famous books in Japanese literature, written by poet Basho.

His father spent three and a half years in the camp, where 14,000 died, and Flanagan has said he had known for a long time “this was the book I had to write if I was to carry on writing”. It took 12 years and five versions to complete.

It took 12 years and five versions to complete. “Each one was a failure then I realised that my father was growing old and frail and for no logical reason it mattered to me that I finished the book before he died.” He talked to his father on the details “as a way of just being with him”.

Shortly before Anzac Day last year, his father, then 98, rang to ask about the book, and was told it was finished. He died later that day.

The chairman said the result was a majority decision that took several rounds of voting and took the judges three hours. “The best and worst of judging books is when you come across one so hard in the stomach that you can’t pick up the next one for a couple of days, you know you’ve met something extraordinary,” he said. “That’s what happened in the case of this one.”

Mr Flanagan’s was the only book by a Commonwealth author to make the shortlist, and beat bookies’ favourites Neel Mukherjee, for The Lives of Others and Independent columnist Howard Jacobson’s J. He is the third Australian to win the prize in its 46-year history, after Thomas Kenneally, and Peter Carey who won it twice.

Jonathan Ruppin, web editor of Foyle’s Bookshops, called it one of the “truly great winners of the prize, one that will be widely read not least because it's impossible to lay aside completely and forget”.

Despite fears, a proposed American invasion failed to materialise in the first year the Booker Prize was opened up to international authors.

Previously open to novelists from the UK, the Commonwealth, the Republic of Ireland and Zimbabwe, the rules were changed last year to allow any international author writing in English where the book is published in the UK to enter.

Two Americans made the shortlist: Karen Joy Fowler for We Are All Completely Beside Ourselves, and Joshua Ferris for To Rise Again at a Decent Hour. The shortlist was rounded out by Scottish author Ali Smith with How to be Both.

Grayling said the judges’ choice should “put to bed” the American issue: “We didn’t bother about the sex or nationality of the authors.”

Last year the prize was won by Eleanor Catton, for The Luminaries, the youngest ever winner at just 28 years old. The 832-page book was also the longest in the prize’s history.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies