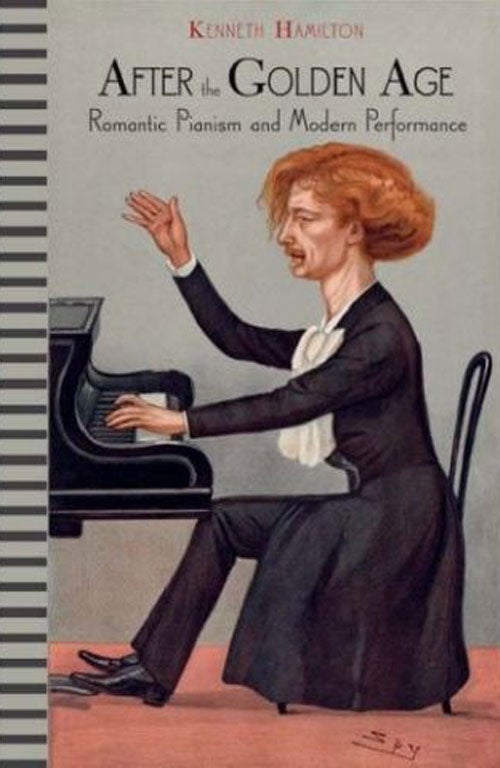

After the Golden Age by Kenneth Hamilton

Liszt with a twist: the piano virtuoso who had a sideline in stand-up comedy

If you had attended one of Liszt's piano recitals in the late 1830s, you might have been invited to place a scrap of paper into an urn with a suggestion for a tune you'd like to hear Liszt improvise upon. You might bump into the maestro himself as he mingled with the audience (wearing his famous Hungarian sabre). Liszt would pull out the scraps, choose a tune and give it the treatment. One night, someone had written: "Is it better to marry or remain single?" Liszt read this aloud and then quipped: "Whichever course one chooses, one is sure to regret it."

Fast-forward to a recent all-Beethoven concert by a famous pianist of today. Before he comes out, a minion appears to warn the audience that they must not cough or make any noise during the performance, because this would destroy the artist's needle-sharp concentration. The artist himself then appears "with grim visage", and proceeds to perform as though dispensing holy writ.

Between these two recitals lie 150 years, during which time concert-giving has changed enormously. The pianist and author Kenneth Hamilton is an ideal guide to the changes, his dry Scottish humour the perfect weapon with which to skewer egos and pomposity.

As he points out in this delightful book, we can't rediscover original instruments and performance practice without speaking of the original audience. Until the early 20th century, it would interrupt the playing with signs of noisy approval, might talk during quiet passages, and might call out to demand that an enjoyable flourish be repeated.

Programming was lively, too. Throughout the "golden age" of Romantic piano-playing, it was not usual to perform whole sonatas as these were thought too severe. Improvisation was popular, as was the habit of "preluding", or making up musical links between items. Players might give themselves breaks while they chatted with friends in the audience. Most pianists were also composers, and routinely included their own pieces. Playing from memory was not required, and sometimes even frowned on.

Customs have certainly changed: but which are better? Silence can indicate rapt attention, and surely players of any era would flourish in such an atmosphere. But what is the point of listeners who are silent because they feel intimidated? Performance styles and audience behaviour are in continual flux, and what seems mandatory today will eventually come to seem merely typical of the early 21st century.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks