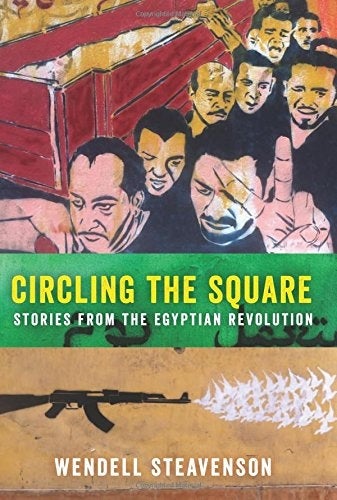

Circling the Square, by Wendell Steavenson - book review: Insurrection at the intersection

Granta books - £14.99

As a televisual event, Egypt’s revolution to overthrow President Hosni Mubarak in 2011 worked: history was being rewritten across North Africa, the revolution was digital, led by Twitter and Facebook and with the incarcerated Google executive Wael Ghonim as the off-stage hero, and Tahrir Square, where the protesters gathered, provided an easy visual shorthand.

But, as Wendell Steavenson notes in this new book, “hindsight eats stories”. That which came after – the fall of Mubarak, the rise of the army and the Muslim Brotherhood – seemed inevitable. But this book, or collection of essays held together by time and place, draws out the unknowability in the revolution.

Steavenson, who covered the revolution for The New Yorker, starts her journey in a balcony overlooking Tahrir, but soon descends. Through the 18 days of the revolution, she finds herself circling the square, the activity which lends its name to this account of not just that moment but also the two years of chaotic politics and military intervention that followed, all from a human perspective.

Her characters are the people she travels with through the revolution: her own translator, Hassan, a young man who’d joined the revolution after working in a deadbeat job in a technical call centre; Nora, one of the well-to-do Egyptians, with a conscience and also helpfully an American passport; a society bachelor Dr Hussein; Dr Beltegi, a member of the Muslim Brotherhood who had installed himself on the square to provide medical assistance.

What Steavenson manages to do is build a portrait of Egypt through looking at it from the street. A trip to a bakery for the earlier bread riots in 2008 gives rise to an essay on how the state pulls the levers of the economy for favour, from subsidising flour to import deals to increase international pull. But the rules change so often and so arbitrarily that everyone feels cheated.

The writing is breathtaking at turns, and Steavenson conveys the hope, chaos and frustration that Egyptians felt, as a powerful document. The plot, if there is one, is about who will triumph. The behemoth of the Egyptian army, that maintains its right to anoint the leader, the revolutionaries, or the Muslim Brotherhood, allegiances switching in the style of Orwell’s 1984.

In the end, the answer is that no one does. In one particularly moving passage, Steavenson returns to the Square, wearily after the latest spasm of violence. An orphan street child runs into her. He and other kids have had tear gas fired at them after throwing stones at the police. The revolution, for a generation uprooted, had just become a way to pass the time.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies