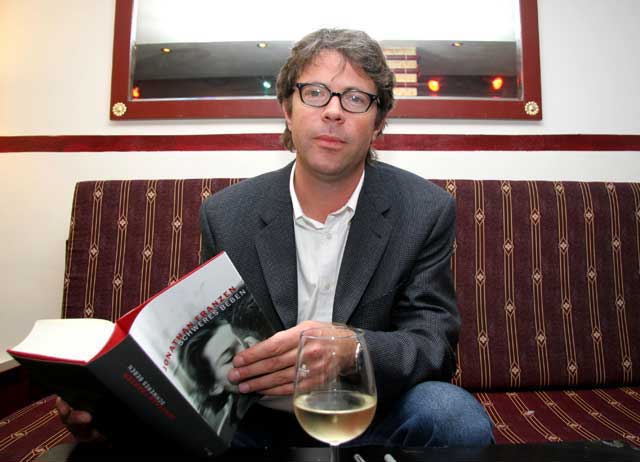

Freedom, By Jonathan Franzen

You might think it presumptuous to compare Jonathan Franzen's towering new novel to Tolstoy. As it happens, I needn't bother, since Franzen has done it for me. Engrossed in War and Peace, one of Freedom's protagonists – the not-entirely-happily married Patty Berglund – is struck by the resemblance of Natasha Rostov's romantic travails to her own divided affections: for her husband, the earnest, loving Walter, and for his best friend, a rogueish minor rock star named Richard Katz. "The effect those pages had on her, their pertinence," writes Franzen, "was almost psychedelic."

Later, Patty wonders whether the Russian epic might even have influenced her subsequent actions. Tolstoy turns up in the pages of Freedom as a comment on the power of fiction to give shape to a reader's life, and as a reminder of Franzen's own ambitions. Panoramic and personal; all-encompassing, yet minutely detailed, Freedom is resolutely a novel in the classic form, a 19th century-style narrative set against the wars – political, social, actual – of the 21st. It succeeds utterly.

It has taken Franzen nine years of work in his sparsely decorated office, on an internet-disabled laptop - one of his principles for writing is the curmudgeonly, but probably accurate, "It's doubtful that anyone with an internet connection at his workplace is writing good fiction" - to produce a follow-up to his previous novel, The Corrections (2001). So pervasive has that book become over the last decade, that when the liberal-intellectual characters in Franzen's new book discuss popular culture – as they frequently do – their failure to mention it seems an almost implausible omission.

The success of The Corrections makes Freedom's release that rare thing for a literary novel: a publishing event. President Obama read it on holiday, then its rave US reviews angered female authors Jodi Picoult and Jennifer Weiner, who protested (not entirely unreasonably) that the New York Times and its ilk give white male writers preferential treatment. Despite Franzen's near-refusal to jump aboard modern publishing's marketing merry-go-round, Freedom has made the leap to the news pages. It has also leapt to the top of the US bestseller lists.

Like its predecessor, this is a social-realist family saga. At its heart are Patty and Walter, a baby-boomer couple from Franzen's favoured Midwest. Financially comfortable, secure in their left-leaning political beliefs, and parents of an outwardly super son and daughter, the Berglunds are nonetheless afflicted by dissatisfaction and disappointment.

Patty, a potential professional sportswoman thwarted by a college injury, is now an overly competitive parent, to the detriment of her family relationships. Her thoughts frequently return to her choice of life partner: should she have plumped instead for Richard, her husband's college room-mate?

Meanwhile, devoted conservationist Walter finds that, in his attempts to preserve an obscure species of warbler, he is forced to compromise – collaborate, even – with the destructive energy companies he most despises. His partner in this endeavour is his all-too-comely young assistant, Lalitha, whose admiration for her boss knows no bounds. Both Berglunds try in vain to outrun their looming depression, while the "freedom" of the title, that abstract condition enjoyed by the developed-world middle-classes, leaves them struggling to decide "how to live".

The Corrections was published in the same week as 9/11, and here Franzen tackles the fall-out from that day, both tangentially and directly. Walter's choice of employer sees him embroiled in Beltway politics, while the couple's college-grad son, Joey, colludes in an unsavoury scheme to sell inadequate vehicle parts to the military in Iraq.

Though it spans the late 1970s to the present, the novel is set predominantly in 2004, at what must have seemed then to be the height of America's culture wars. It interrogates the liberty that the Bush administration sought to spread indiscriminately, and finds it lacking. To borrow Donald Rumsfeld's phrase, "Freedom is messy."

Unlike the Lamberts of The Corrections, who owed much to the author's own family, Franzen professes to have imagined the Berglunds from scratch – formative years and all. He allows his obsession with migratory birds (expounded upon in his 2006 memoir, The Discomfort Zone) to be shared by Walter, and the paragraphs he devotes to their decline are as moving as many of the more human moments. In nature, Walter explains, "Things live or they don't live, but it's not all poisoned with resentment and neurosis and ideology. It's a relief from my own neurotic anger."

If there is an author surrogate, however, it's middle-aged rocker Richard, whose glancing experience of fame surely mirrors Franzen's own. After toiling for years in creative obscurity, Richard finally releases a critically adored album that earns him the respect of the in-crowd. Famous enough to be recognised by those in the know, but obscure enough to avoid them when he prefers to, he both cherishes and despises his success. His internal contradictions are thoroughly convincing.

This is perhaps Franzen's primary skill, to give each of his characters such comprehensively realised psychologies. Even the Republican sympathies of Walter's son Joey are plausibly rooted in the father-son relationship – and Franzen, a declared liberal, manages to describe the motivations of modern conservatives without too much knee-jerk condescension.

The book's one great forgivable flaw is to ascribe a significant portion of the story's telling to Patty, who composes a memoir in the third person at her therapist's suggestion. So close is her voice to Franzen's own that a reader can't help but wonder why this frustrated housewife isn't a published novelist. She watches "innumerable buses roll by outside the windows, each trailing a wake of shimmering filth"; she admires two young children who "seemed to have been born with a Victorian sense of child comportment – even their screaming, when they felt obliged to do it, was preceded by a moment or two of judicious reflection."

Tellingly (bearing in mind her reaction to Tolstoy), Patty's autobiographical bursts, when read by her fellow characters, themselves become drivers of the narrative. Like Freedom itself, their effect is first melancholy, then redemptive. Franzen's command of structure and his shifting chronology is enviable. He can move tonally from the casual and colloquial to the grand inside a paragraph. His understanding of individuals is matched by his sure grasp of the culture. Despite the characteristically grumpy asides about Twitter and various other aspects of 21st-century modernity, he holds his nose long enough to use a viral video as a plot device.

Though it contains a few too many lengthy dialogues about the correct approach to environmentalism, Freedom is not lofty or detached. It's a warmer book than The Corrections; one that loves its characters for their flaws, not in spite of them. Its pages fly by like a pulp thriller – and it's only half as long as War and Peace.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks