His Own Man by Edgard Telles Ribeiro; trans Kim Hastings, book review: The dark side of politics in Latin America

Stories about gangsters share much with stories about diplomats, especially in dictatorial times: crime, power, women, money, fashion, violence, deception. Both also tend to be stories about individuals operating in a network far bigger than them. Of course, a gangster is never anything other than his own man (or woman).

But what about a diplomat? Most diplomats go on regardless of changes in government. This is part of the game. However, it is a rare diplomat who does not just survive, in some reduced capacity, after a drastic change of government, but rises further. When the country is Brazil, ruled by the holy trinity of church, bureaucracy and military, then surely such a diplomat can only be his own man?

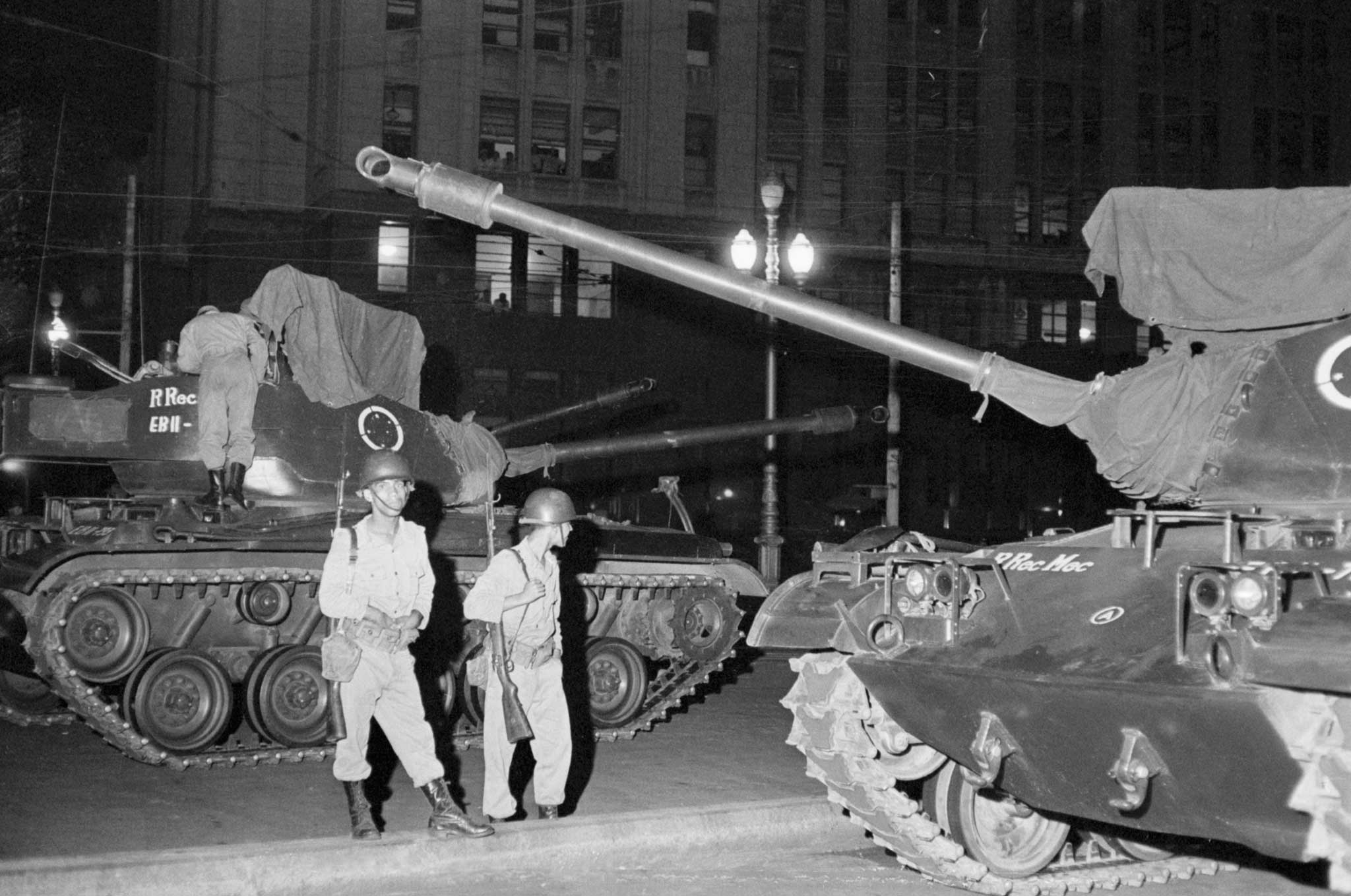

Marcílio Andrade Xavier – "Max"to his friends – is such a man in Edgard Telles Ribeiro's His Own Man. Charismatic and Machiavellian, Max makes the right jump by kissing a cardinal's ring when, in the 1960s, General Mourão Filho's troops overthrow the democratically elected government of the leftist President, Joao Goulart.

Helped by powerful patrons, under the all-seeing blind eye of the CIA, Max shines as successive "general-presidents" rule Brazil for two decades and then dexterously survives when the leftists return to power. This is a readable novel about the labyrinth of recent Latin American politics, and it belongs to what is almost a "sub-genre" of dictator novels in Latin America (Bastos' I, the Supreme, for instance) and a larger global genre of "diplomat" fiction.

Ribeiro provides a convincing portrait of a man who, partly due to what he is and partly due to the times, ends up aiding and abetting policies which imposed themselves in terms of raw fear, terror and physical oppression elsewhere. The narrator, a younger diplomat who admires Max, glimpses the physical aspects of the fear unleashed by the suave activities of people like Max only once in the novel, captured in a crucial letter.

Can a man at the heart of power be his own man in such times? Of course, but only to the extent that the gangster is always his own man. Ribeiro's novel suggests this, but does not really engage with its repercussions.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies