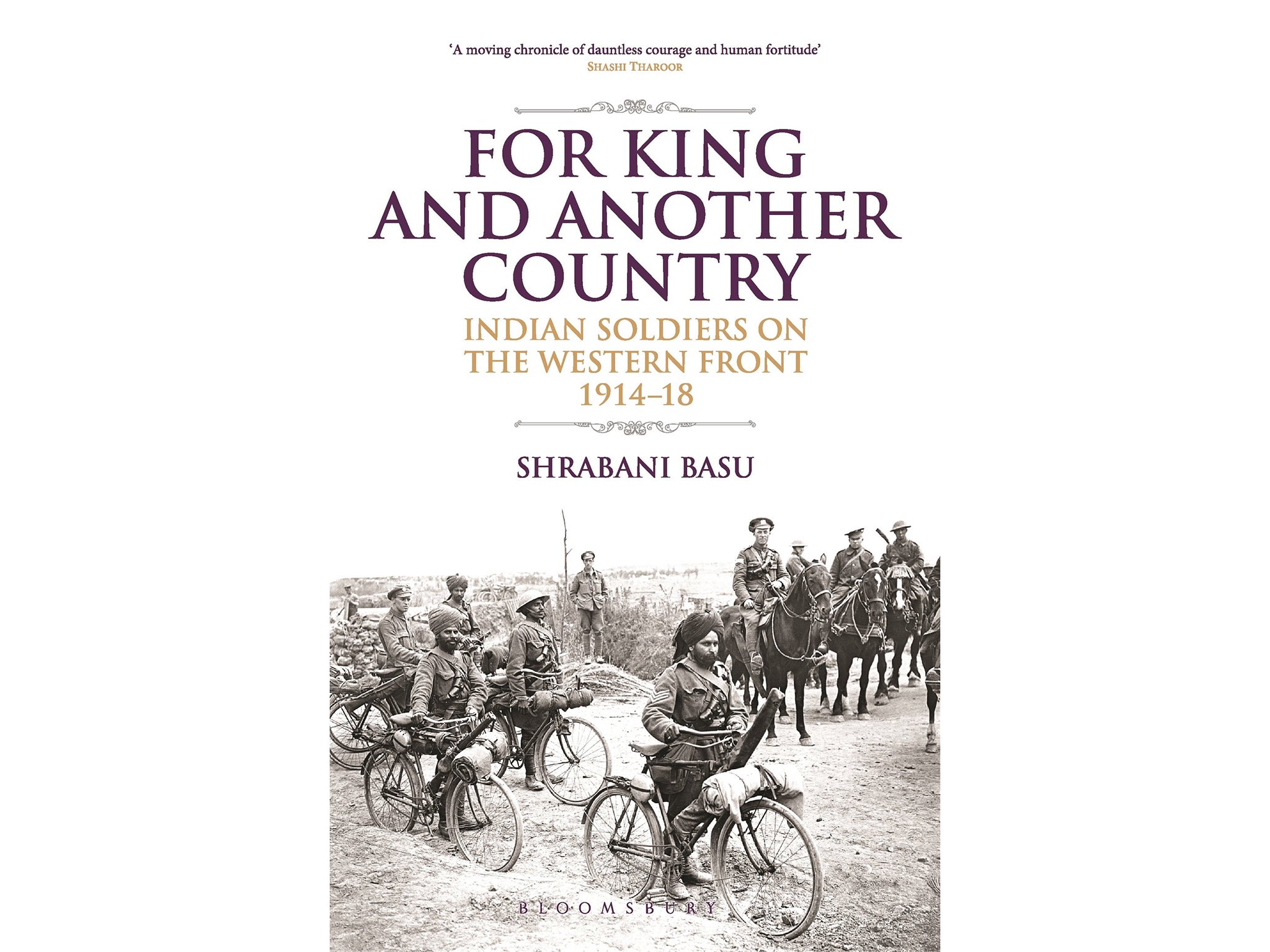

For King and Another Country: Indian Soldiers on the Western Front 1914-1918 by Shrabani Basu, review: Forgotten fighters of the First World War

India contributed nearly £250m and 1.2 million fighting men to the Allied powers’ cause – 72,000 of whom never returned

“So what did Indians do during the First World War, daddy?” is not a question many ask. Yet India contributed nearly £250m and 1.2 million fighting men to the Allied powers’ cause – 72,000 of whom never returned home.

The problem is that while the war is seen as a fight for freedom, India, unlike Britain’s white dominions, was not free, and in August 1917 the war cabinet estimated it would take Indians 500 years to learn to rule themselves. And the soldiers could not claim to represent all of India. Under Britain’s very special apartheid recruitment system, Indians were divided into martial and non-martial races with Lord Roberts, the commander-in-chief, arguing that “the warlike races of northern India” could not be compared to “the effeminate peoples of the south”. Even then, Roberts felt: “Native officers can never take the place of British officers. Eastern races, however brave and accustomed to war, do not possess the qualities that go to make good leaders of men.” So there were no Indian officers and many British soldiers who encountered Indians for the first time took an instinctive dislike. For John Charteris, a staff officer of the British services, Indians were the dregs of the Western Front. He described them as “not as good or nearly as good as British troops. How could they be?” And Frank Richards, a private of the 2nd Battalion, Royal Welch Fusiliers, said “the bloody niggers were no good at fighting”.

Sharabani Basu quotes neither view as she sets out to tell the story of how 138,000 Indians who fought in Flanders and France overcame both racism and a world they had never encountered before to win six Victoria Crosses on this front. With the Indians largely illiterate – Illustrated Magazine sent by London clubs to the front was very popular – Basu had no soldiers’ memoirs to work with. But using letters written by those who were literate, she paints a vivid picture of an Indian view of trench warfare that was very different to that of the British. So while the wounded were well looked after in British hospitals, English nurses were not allowed to care for them, the British horrified that there may be racial mixing. In one Brighton hospital, the restrictions were so severe that it was called the “Kitchener Hospital Jail” and led to a shoot-out. In contrast, the French were racially more tolerant. Their women were allowed to show affection and even “mothered” some of the Indians.

This is a fine book that shows for all the talk of Britain and India having a shared history, for the Indians it was very curious kind of sharing.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies