Mislaid and the Wallcreeper, by Nell Zink - book review

Fourth Estate - £20

Jonathan Franzen observed of the American writer Nell Zink, who lives in a town just outside Berlin, that “everything in her life beginning with her own name sounds made up: Nell Zink from Bad Belzig!”

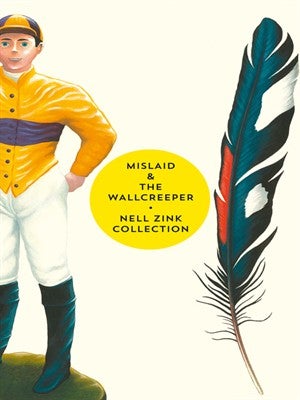

Zink crossed Franzen’s path when she wrote to him in response to an article he had published on the illegal hunting of songbirds, and her continued correspondence was so electric that he urged her to write and publish. The recommendation of Franzen, so clinical in his writing, should not deter the reader from Zink: she is quite different, and thoroughly wild. Two of her novels have just landed simultaneously in Britain, in a bright yellow boxset: The Wallcreeper, named after a rare mountain bird, and her next novel Mislaid, which won a six-figure advance after Franzen’s agent took it on.

While Zink’s strange name and life story intrigue interviewers, no one really questions Karen Brown, one of the central characters in Mislaid, a blonde, blue-eyed girl growing up in the tobacco country of Virginia whose birth certificate says she is black. Mislaid is a brilliant comedy of errors, often about getting laid, told at breakneck speed.

First, Peggy Villaincourt arrives at the conclusion, as a (white) child wearing ill-fitting gym kit, that “she was intended to be a man”. As a young woman, she crops her hair, dons an outfit of black khakis and black sweaters, and signs up to an all-women’s college in Virginia, a hotbed of 1960s feminist alternative culture, perfect for the aspiring playwright. That identity doesn’t last long. Across the lake from her college is Lee Fleming, the gay and decadent son of an old Virginian family, who writes poetry and teaches creative writing to the girls. He’s safe enough for an intellectual love affair, that is until the two end up in his canoe, hips rocking against each other. From this accidental coupling comes a son, Byrdie, and later a daughter Mireille, and a decade of her diminished to dowdy housewife while Lee holds salons for gay intellectual liggers from the big cities, and chases the boys and girls around campus. Peggy eventually cracks, kidnaps Mireille – Byrdie won’t come – and drives off in the opposite direction to that which Lee expects: not to the bright lights and ambition of New York, but to a rural backwater, a shack in tobacco country with a passport into black life – the birth certificate of a young black girl who has died. So, Mireille Fleming becomes Karen Brown, and enters a poor black school, and Peggy becomes Meg, who bags up cocaine to make ends meet.

Four identities have already been burned through within the first 40 pages – the question of ditching your given race particularly apposite just after Rachel Dolezal, the President of the Spokane National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, was outed as white passing for black. But Zink goes further: all the mantles of the privileges of being straight and white and rich are dumped on the floor. Add to that the amount of laying, or mislaying, as the book skips through gay sex, lesbian sex, interracial sex, underage sex, and this is quite a romp through every nook and cranny of identity.

And why not? While white and straight, as Lee Fleming’s rich parents are, struggle to morph with the times, the “others” in this book – women or black or gay – get to play, drift, fall in love, fail. The only counterpoint to this is Karen Brown’s boyfriend, Temple, a pillar of society. You cannot escape the Shakespearian element, the mechanics of comedy and farce that work through the novel, and towards the last third there comes the inevitability that the paths of Lee and Peggy, Mireille and Byrdie will collide in the future.

But the drive there is delicious: Zink’s prose revs and careers through the plot. Before you’ve blinked a decade of debauchery, misery, deceit and hedonism flashes by, and you’re awaiting the moment of impact.

The companion piece in this volume, The Wallcreeper, starts at the other end with a crash, as a car smacks into a rare mountain bird on a Swiss road. The driver, an American scientist and ornithologist, steps out to rescue it, while his wife is crumpled by the impact. The first sentence takes the whole book to unravel: “I was looking at the map when Stephen swerved, hit the rock, and occasioned the miscarriage.” The bird – the wallcreeper – survives, thrives and almost becomes domesticated before its desire to mate leads it off to its natural bloody end.

This is a slimmer volume, straying asymmetrically through its story of a partnership falling apart, in an uncontrollable environment, with a feeling that there’s a heavy dose of autobiography in it. It is the one to read first.

Franzen might be right on this writer: Zink, not a product of the fevered American literary scene, but a fiftysomething novelist by accident, has written two books both worth talking about in the best salons in town, which will unsettle them in turn. One hopes she does not become domesticated by the fame.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks