Paperback reviews: From A Brief History of Seven Killings, by Marlon James to The Insect Rosary, by Sarah Armstrong

Also In Montmartre: Picasso, Matisse and Modernism in Paris, 1900-1910, by Sue Roe, The Emperor Far Away: Travels at the Edge of China, by David Eimer and Curtain Call, by Anthony Quinn

A Brief History of Seven Killings, by Marlon James - Oneworld, £8.99

****

A Brief History of Seven Killings is a misleading title: Marlon James’s third novel is not brief – it weighs in at some 700 pages – and the death-toll exceeds seven by quite some margin. It is, though, an ambitious and catchily-written book, a polyphonic tale of Jamaica and Jamaicans that spans three turbulent decades.

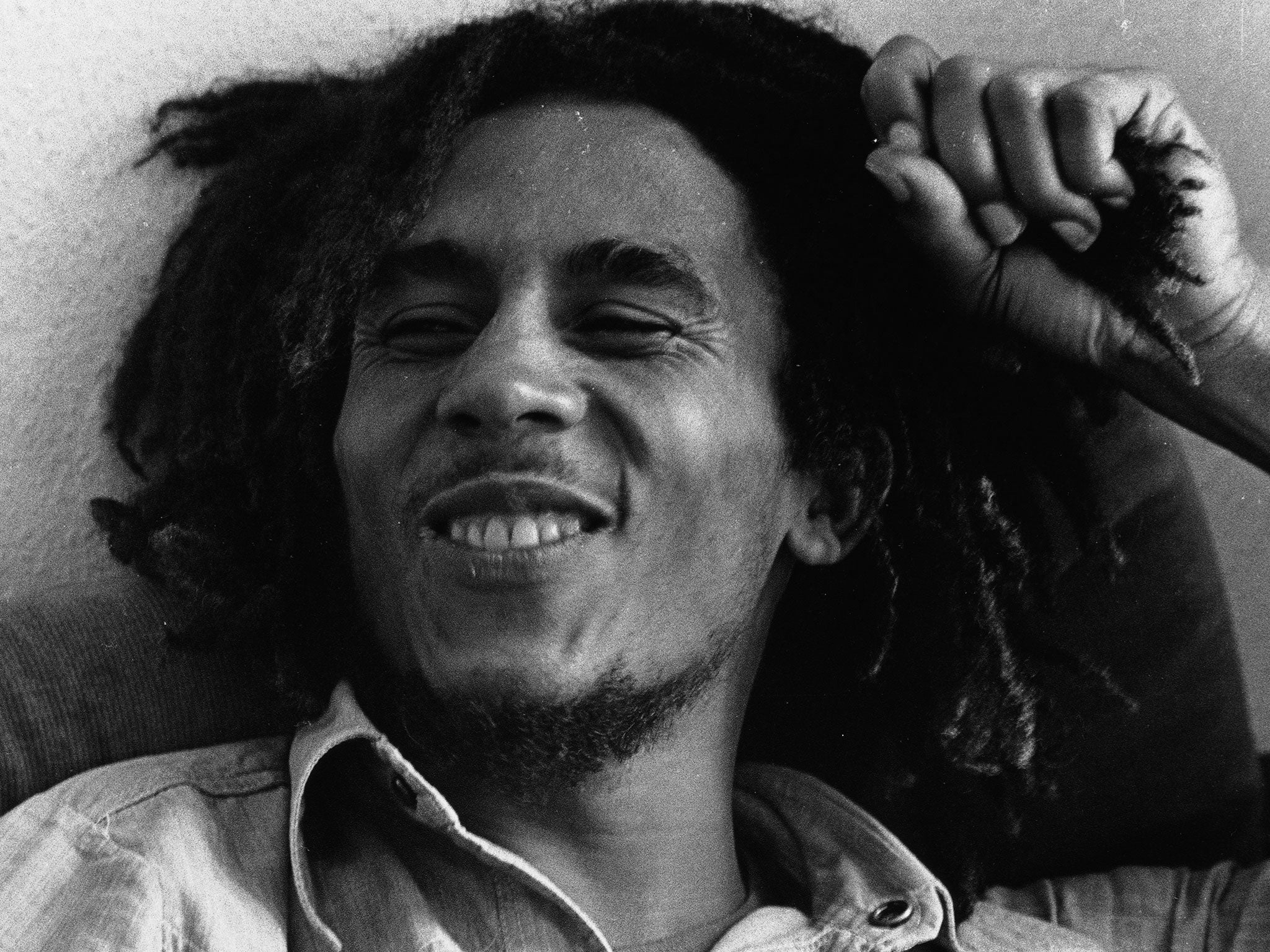

At its centre is a true story: in December 1976 gunmen entered Bob Marley’s home and opened fire. Marley took a bullet in the arm and narrowly escaped with his life; his wife and manager were also injured. He performed onstage at a peace concert in Kingston a few days later, bandaged but unbowed. Gangsters, politicians and the CIA are variously held responsible for the assassination attempt – but the truth remains mysterious.

The narrative revolves languorously around these events, like an LP turning at half-speed. Marley himself appears only briefly, and others refer to him obliquely as “the Singer”, a name freighted with deific significance throughout. Narrating is a cast of characters – gangsters, groupies, even ghosts – whose lives are in some way touched by Marley and his music. As they recount their stories, the novel builds into a portrait of the island that eschews the sunny stereotypes; James’s Jamaica is a world of police corruption, brutal violence and political turmoil.

Critics have compared James to Quentin Tarantino, and his book can be irritating in the same way that Tarantino is irritating, whenever he falls in love with one of his own wisecracking riffs. It is overlong and occasionally self-indulgent. The coda, set amid Jamaican gangs in New York in the 1990s, bears only a tangential relationship to the rest of the book.

These flaws may prevent the novel from winning the Booker Prize, for which it was long listed last month. Read it anyway. This is fiction of vast ambition and impressive achievement, a feat of literary ventriloquism that sparkles with a blackly-comic wit.

In Montmartre: Picasso, Matisse and Modernism in Paris, 1900-1910, by Sue Roe - Penguin, £10.99

***

Today, the name Montmartre brings to mind familiar images: Expensive hotels, tourist tat, the Moulin Rouge’s ersatz windmill. But at the turn of the 20th century, it was home to some of the leading artists of the Belle Epoque: Picasso, Matisse and Modigliani among them. By day they would work in decrepit studios and take in the views across the city from the Butte – which was then topped with gardens, (real) windmills and an extensive slum – by night they would sip tax-free wine in cafes wreathed in cigarette-smoke.

Sue Roe’s book delves into this milieu and emerges with a very readable group biography. Nothing she tells us is particularly new, but the telling is elegant and engaging. There are some memorable passages of ekphrasis – Picasso’s The Absinthe Drinker seems to emit “the scents of musk and patchouli oil, the chatter of the crowd, the hum of accordion music” – and the account of the rivalry between Picasso and Matisse is nicely done. “[We are as] different as the North Pole is from the South Pole,” Matisse recalled, icily.

The Emperor Far Away: Travels at the Edge of China, by David Eimer - Bloomsbury, £8.99

***

China’s strong centralised government and the dominance of its Han ethnic group tend to reinforce Westerners’ views of a monolithic culture. But, as journalist David Eimer points out, China is really more of an empire than a single country – built piecemeal over the centuries through the conquest of far-flung lands and peoples.

Eimer’s book recounts his journeys to China’s perimeter regions, where he meets those for whom, as the Chinese proverb has it, the mountains are high and the emperor far away. He visits the Tibetan plateau, Uighur communities and Korean villages in the frozen Northeast. The first-person travelogue elements here are unremarkable; Eimer’s better when he’s weaving his (impressive) research into the historical and political background of the borderlands. It’s a timely book, given President Xi’s putative imperialist ambitions.

Curtain Call, by Anthony Quinn - Vintage, £8.99

***

London, 1936: Actress Nina and toffish portraitist Stephen meet in a posh hotel for a tryst. There Nina inadvertently interrupts the notorious “Tie-Pin” serial murderer at work. Together, the couple try to track down the killer against a backdrop of West End glamour, fascist thuggery and Soho sleaze.

A new Anthony Quinn novel is always welcome, although Curtain Call isn’t a patch on his previous effort, The Streets, which was a relishable tale of Dickensian London that also had something to say about the inequality of the city in our own time. In contrast, this novel is simply an entertaining diversion: all glittery theatrical surfaces, nothing more profound. Still, the narrative bowls along and there are some terrific characters: I enjoyed the portrait of Jimmy Erskine, a bumptious theatre critic and souse based on James Agate.

The Insect Rosary, by Sarah Armstrong - Sandstone Press, £8.99

**

Sarah Armstrong’s debut novel tells the story of two sisters. Bernadette and Nancy spend their holidays with their mother’s family in rural Northern Ireland, where they are intrigued by the “Byronic” figure of Tommy, a shady character involved in theft, violence and worse. Years later, they return to the family’s cottage to reckon with the past and patch up their broken relationship.

Armstrong begins impressively, tacking back and forth between the 1980s and the present day and shifting perspectives between Bernadette and Nancy; the novel promises to develop into a nuanced exploration of both a sibling rivalry and the “strange abbreviated country of Northern Ireland” during the Troubles. Sadly, though, the narrative loses its way: the sisters’ relationship frequently rings false and the villainous Tommy is thinly drawn.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies