Spy of the First Person by Sam Shepard, book review: A rich and moving final work

The Pulitzer-winning writer and actor's last work is clearly partly autobiographical, narrated by a man in his later years being treated for a debilitating illness, as he looks back over his life and reflects on a changing America

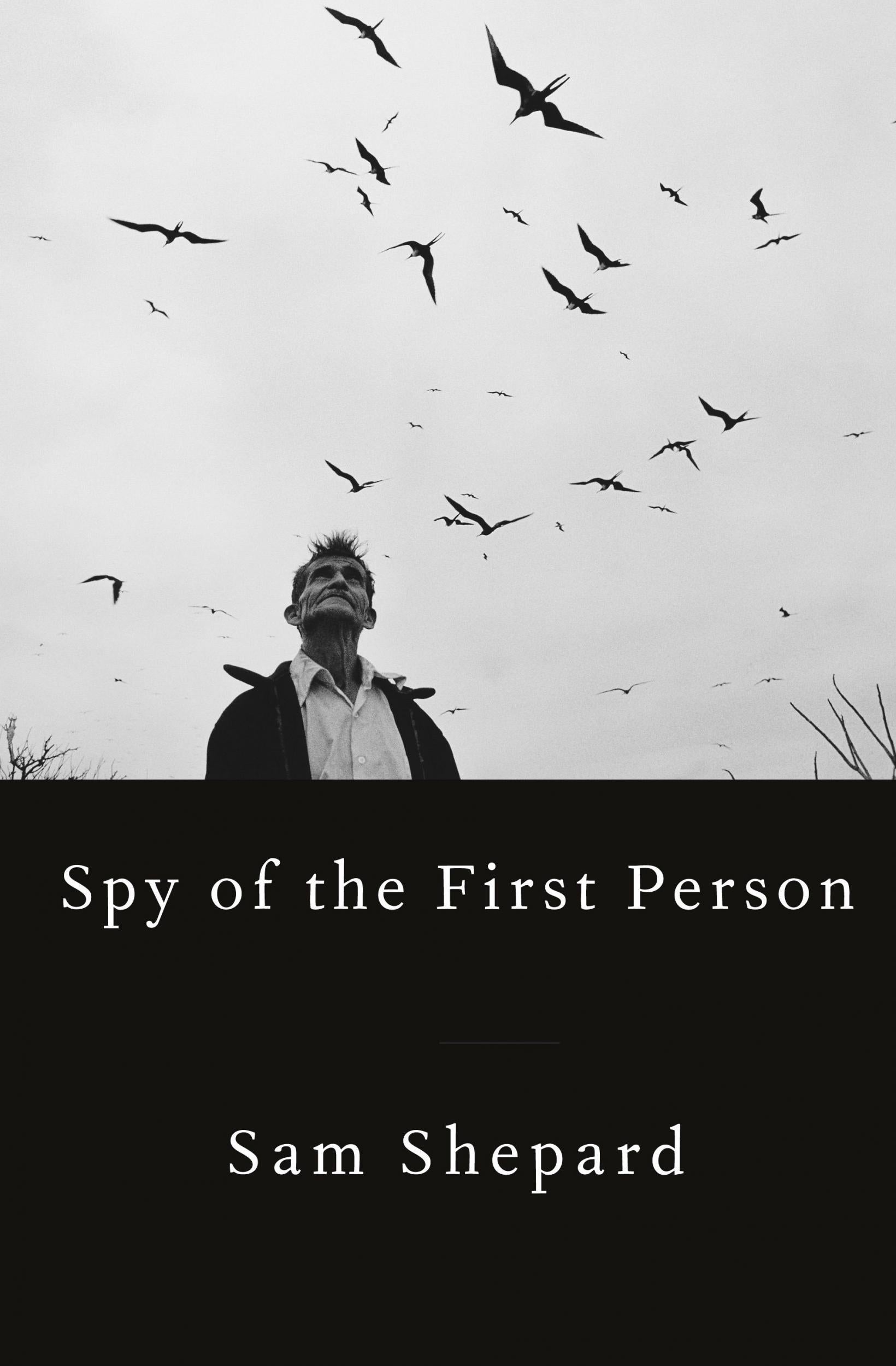

The Pulitzer-winning playwright Sam Shepard died of motor neurone disease in July, leaving behind a formidable legacy of nearly 50 plays which often put forward unwaveringly bleak critiques of American ideals.

From the late Seventies he also had a parallel career as a character actor in the classical mould, from his Oscar-nominated performance as the astronaut Chuck Yeager in 1983’s The Right Stuff to his autocratic patriarch in the Netflix family melodrama Bloodline. He also wrote novels, short stories and screenplays for films such as Wim Wenders’s haunting Paris, Texas.

He was working on another novel right up to his death, writing by hand and then dictating into a tape recorder with the help of his daughter and sisters. Friend and former girlfriend Patti Smith helped him edit the final manuscript. Clocking in just over 80 pages, Spy of the First Person is clearly partly autobiographical, narrated by a man in his later years being treated for a crippling illness. Sitting in a rocking chair on the porch of his house in southern California’s Colorado desert and being cared for by his family, he looks back over his life and reflects on a changing America. All the while a younger man in a property opposite watches him, fascinated by his enigmatic neighbour.

Spy of the First Person captivates in its distillation of many of Shepard’s enduring themes – the death of America’s frontier, identity and loneliness. The old man reflects that in the surrounding desert “there used to orchards as far as the eye can see”. But even in his parents’ era such a landscape had turned to “black plastic blowing from barbed wire” and “dead pigeons in the road”. In a time when migrant workers added to local colour rather than constituting a threat, even his sick mother, who had immigrated illegally from England, faced deportation for lacking the right papers. Where exactly does any of us really come from, he muses.

But amid the conflicted nostalgia, the old man confesses to his son in his mind to a secret criminal past and a deranged act of violence. Memory is for him “like a scab ... that you pick at”. From his position across the road the younger man sees “big bad birds” swooping around the older man’s house, and reflects on “the progressive nature of things ... things run down”. There’s foreboding amid the wistfulness, but it’s tempting to read this novella as Shepard looking at America in a more elegiac light. There’s a wonderful reference to an organisation called the Shriners, a branch of the masons where “guys from the Midwest” dress up as Arabs, “full of Arab pride” – a baffling but wonderful concept which goes to the heart of America’s strangeness.

Spy of the First Person ends with the old man going for a tequila-fuelled meal at a Mexican restaurant with his family – “the menu had a logo of a lighthouse. Lonely illuminated.” Amid a “cacophony of voices”, they talk Trump, “the country in a Mexican stand-off”.

Shepard illuminates loneliness beautifully in this slight but rich and moving final work. In the final lines the old man sees “the moon getting bigger and brighter ... two sons and their father, everyone trailing behind”. Shepard’s valedictory message is one of hope.

‘Spy of the First Person’ by Sam Shepard is published by Alfred A Knopf, £13

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks