The End of the Cold War 1985-1991, by Robert Service - book review: Did the cold war end or was it just asleep?

The Gorbachev era is brought to life in rich detail yet some gaps remain

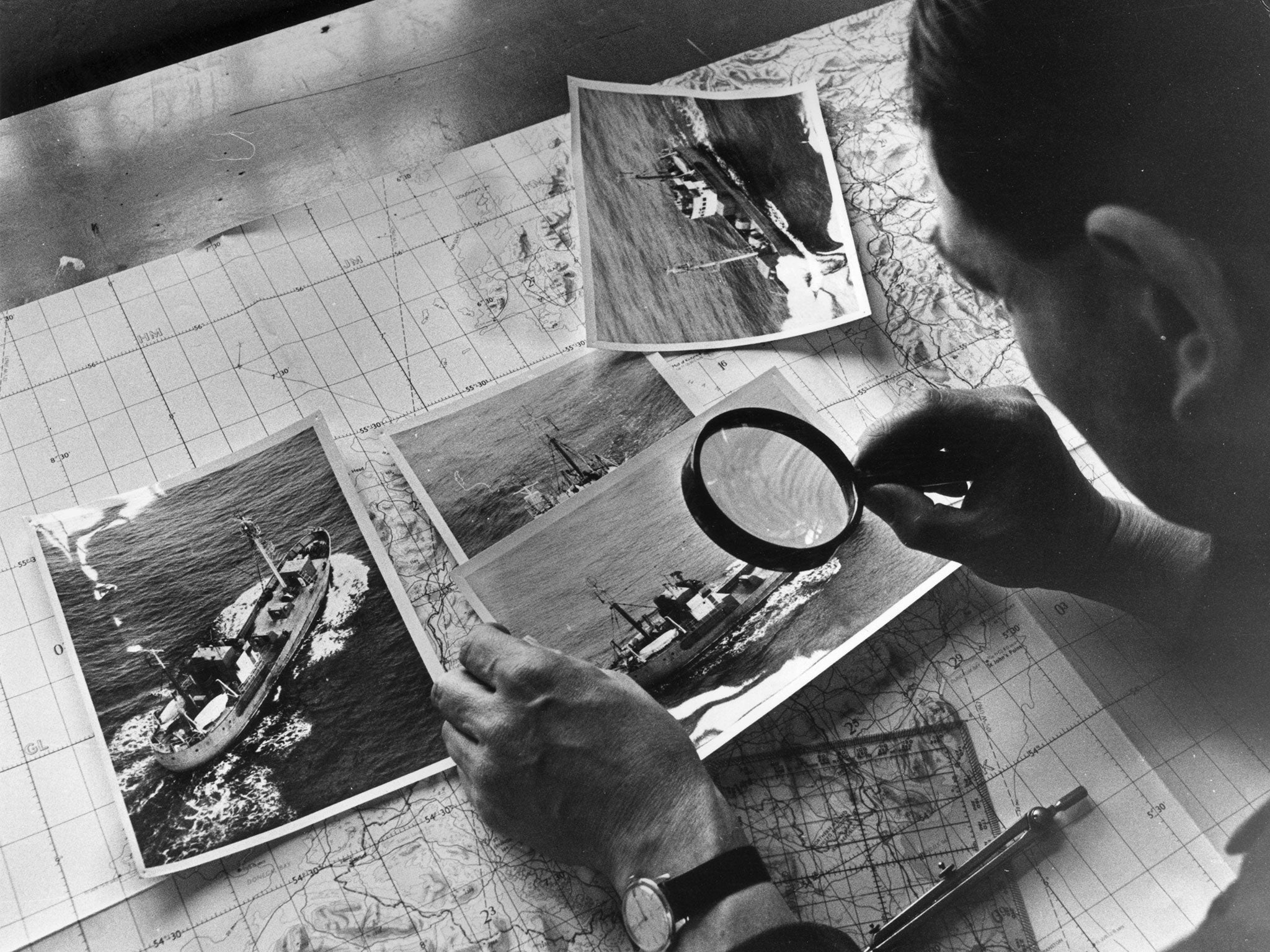

This is an enormous book, in size, scope and detail, and it landed on my desk just as Russian warplanes started bombing sites in Syria - military action decried by most of the Western world that could be interpreted as a direct challenge to Robert Service’s thesis. Almost a quarter of a century after the author’s chosen date for the end of the Cold War, the question might be posed: did it really end, or was it just asleep?

To give him his due, Service raises that very question, and others, in his succinct Postscript, largely in relation to Ukraine. In fact, though, his previous 500 pages provide a robust answer. The Cold War was a particular period, fraught with particular fears, the most terrifying of which was the prospect of “mutually assured destruction” as a result of US-Soviet nuclear war.

Between them, Mikhail Gorbachev, Ronald Reagan, George Bush, and a shifting supporting cast that included Margaret Thatcher, Helmut Kohl and Francois Mitterrand, brought the risk of that sort of East-West confrontation to an end. Service acknowledges the part played by individual leaders, and I agree. Amid all their doubts, preconceptions and personal rivalries, those who found themselves in positions of responsibility in those turbulent times generally acquitted themselves well. Whatever is happening now, whether in Ukraine or in Syria, it is not the return of that Cold War.

I should perhaps declare an interest here. The exact period covered by Robert Service, professor of Russian history at Oxford, is also the period that I spent as a Kremlin-watching journalist, first at the BBC, then as Moscow correspondent for The Times. His every chapter brings back in its minute details the absorbing - and, yes, exciting - events of those years.

Paragraph by paragraph, the names he mentions conjure up the pictures and sounds of those individuals in my mind’s eye: the gruff, the charming, the voluble, the vain, the unreliable, there they all are. One of his first comments on Gorbachev is perhaps the most perceptive - that “his passivity was one of his conjuring tricks”. Gorbachev’s political strength to a degree lay less in what he actually did than what he chose not to do.

But what if you did not live and breathe those times? This is one question that remains. Might the more general reader find it hard to tell the wood from all those trees: Ogarkov, Ustinov, Varennikov, Boldin, Dobrynin - I am picking the names almost at random. Might there be a risk of indigestion? Who are the imagined readers of this authoritative and exhaustive book of record? At least the chapters are bite-sized and well-labelled. If you are not in the mood for the finer points of negotiations on medium-range missiles, you know what you are skipping.

Service has had the benefit, as he generously states, of numerous memoirs and the archives - including US and Soviet archives - that have been opened in the years since the Soviet Union’s collapse. This is where the new material lies. The personal and ideological divisions in the Soviet Union’s supposedly one-party leadership emerge as starkly as the open disagreements between political factions in the United States. At the time, we Kremlin-watchers could only read signals.

Service illustrates the many rifts Gorbachev had to bridge, and even the shouting matches that sometimes ensued. The fury of the usually genial foreign minister, Eduard Shevardnadze, when Gorbachev appointed the veteran Middle East specialist, Yevgeni Primakov, as a special envoy, shows that Western politicians have no monopoly on self-esteem. As for the much-vaunted “special relationship” between Gorbachev and Thatcher, it would seem that she was more enamoured of him than he of her.

Amid such riches, it seems churlish even to hazard at gaps. But I missed any mention of the “Pan-European picnic” of August 1989, which opened the border between Hungary and Austria, the first chink in the iron curtain. The evolution of the grassroots democracy movement in Russia is rather glossed over, even though it forced the pace of Gorbachev’s political reform.

Nor does Service mention Shevardnadze’s appeal for foreign assistance after the Armenian earthquake - a landmark in the opening up of the Soviet Union. And while he devotes some space to Marshal Akhromeev, the hardliner who became Gorbachev’s military adviser, he omits his death: Akhromeev hanged himself in his office, in full uniform, after the failure of the 1991 coup - a potent symbol, if one were needed, of the ending of the Cold War.

More generally, I missed some atmospherics - the nail-biting sense of risk and excitement that pervaded those times; the real chaos into which Gorbachev’s Beijing trip descended because of the pro-democracy demonstrations, ditto the Malta summit, its arrangements altered minute by minute because of mere physical storms; protocol whipped away by the wind.

If I had just one criticism of this book, however, it is that the author’s attention to the “what” and the “how” leaves the “why” almost unexplored. It could be argued, perhaps, that there were no big reasons why the Cold War ended, only a myriad small ones, whose combined weight eventually crushed the Soviet system and, with it the Cold War. In that case, the whole of this volume essentially constitutes the “why”.

It probably depends on how you like your history. But I regret just a little, that after offering his readers such an abundance of superbly organised material, Service does not also venture more of his own judgement on the forces that moved these particular nations.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments