The Magnificent Spilsbury by Jane Robins

According to George Orwell, the Brides in the Bath murders gave "the greatest... pleasure to the British public". The case, with its unlovely spinsters duped by a conman, climaxed in a courtroom clash between the theatrical "Great Defender" Edward Marshall Hall and the expert witness, pathologist Bernard Spilsbury.

Like a tale by Conan Doyle, it included a determined detective, midnight exhumations, a dramatic re-enactment, a whiff of hypnotism, clues deciphered by a renowned scientist and sufficient mystery for crowds to cram the court. Newly wedded Bessie, Alice and Margaret all drowned in their baths without a struggle, and temporarily blew the 1915 Zeppelin raids from the front pages.

Jane Robins tackles the case with gusto, linking it with the genesis of forensic science and casting Spilsbury as her hero. But her title is misleading, as the pathologist doesn't take centre-stage. Instead we have a gripping retelling of the crime against a backdrop of the Titanic, Suffragettes and the First World War, highlighting the social context that allowed a psychopath to manipulate eight women, wed seven, defraud six and kill three.

If George Joseph Smith exercised "extraordinary power over women", his milieu was hardly glamorous. The action happened in towns like Herne Bay, Southsea, Blackpool, and boarding houses where there was bread-and-butter for tea but tenants supplied their own fish supper.

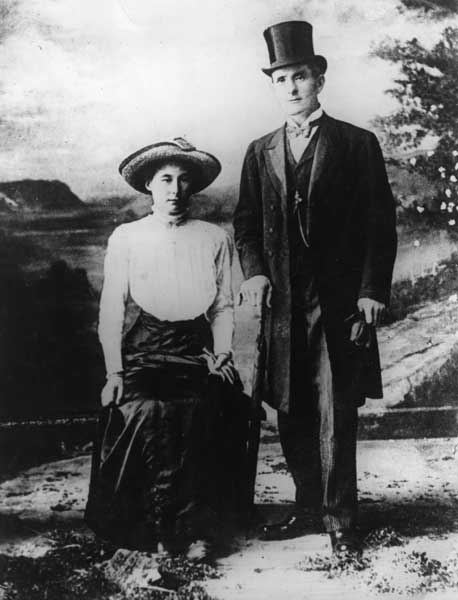

In 1910, when Bessie Mundy eloped with "Henry Williams", women outnumbered men by half a million. They couldn't vote, but for many a more pressing issue was whether – like 33-year-old Bessie – they would end up old maids. Pretty, fat Alice Burnham wedded George Smith within weeks of knowing him. Her marriage lasted three days; 12 months later, 37-year-old Margaret Lofty secretly exchanged vows with "John Lloyd" and was dead the next evening.

All three were socially superior to Smith. Bessie enjoyed independent means ( having inherited £2,500 from her bank-manager father). Alice, a trained nurse, had savings too. Robins struggles to explain their susceptibility. Were they sexually in awe, intimidated or just desperate for married respectability? Bessie once complained a brutish landlord "touched" her. Alice had contracted gonorrhoea and Margaret, the clergyman's daughter, had almost married another bigamist.

On her wedding day Bessie was demanding money from her family, as was Alice. Menacing letters from Smith were fired off to anxious relatives. The rings had scarcely been put on before wills were drawn up, life policies and annuities taken out. Each bride visited a doctor for supposed headaches or fits. The ensuing drownings then appeared to be accidental deaths resulting from fragile health.

Meanwhile, Spilsbury was making his name. Having shone at Dr Crippen's trial he was now squaring up to Marshall Hall as the Home Office Pathologist. The Great Defender's own reputation rested on showmanship – less legal brilliance than persuasive interpretation. But Hall's modus operandi belonged to another era. Science and its practitioners were the new courtroom stars. A fist clenching a bar of soap, goose flesh on a thigh, and Spilsbury's ideas on sudden submersion helped secure a conviction. Smith hanged, and from then on Spilsbury wielded extraordinary influence.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks