The Undivided Past: history beyond our differences, By David Cannadine

A leading historian makes a spirited case for harmony against the myths of identity politics

If you ever go to Agra, don't confine your visit to the Taj Mahal, the Fort and the other gorgeous Mughal tombs of Sikandra and Itimad-ud-Daulah. Some 25 miles to the West lies the rose-red hill-top ghost town of Fatehpur Sikri, the royal capital custom-built by the Emperor Akbar, occupied for 14 short years in the late 16th century and then, mysteriously, abandoned.

Get money off this book at the Independent bookshop

Here, Akbar pursued his dreams of eclectic learning and enlightenment, and here he summoned scholars and clerics from all faiths - his own Islam, but also Hindu gurus, Catholic priests, Zoroastrians, Jains, Jews and Buddhists - to determine via debate not what divided them but what they shared.

Akbar, who pursued this vision of a common humanity just as much of Europe tore itself to shreds in fanatical wars of religion, has a brief cameo in this impassioned plea by the historian Sir David Cannadine for an understanding of the past that finds its focus in our age-old conversations and collaborations, rather than in conflict.

Cannadine offers a spirited, if relentless, challenge to the "us and them" mentality and the "allegedly impermeable divides" it finds between people of different communities and backgrounds. He takes his cue from the strident "clash of civilisations" rhetoric of the post-9/11 years, and extends his critique of "binary divisions" to cover oppositions and antipathies rooted in ideas of faith, nation, race, class, gender, and in "civilisation" itself.

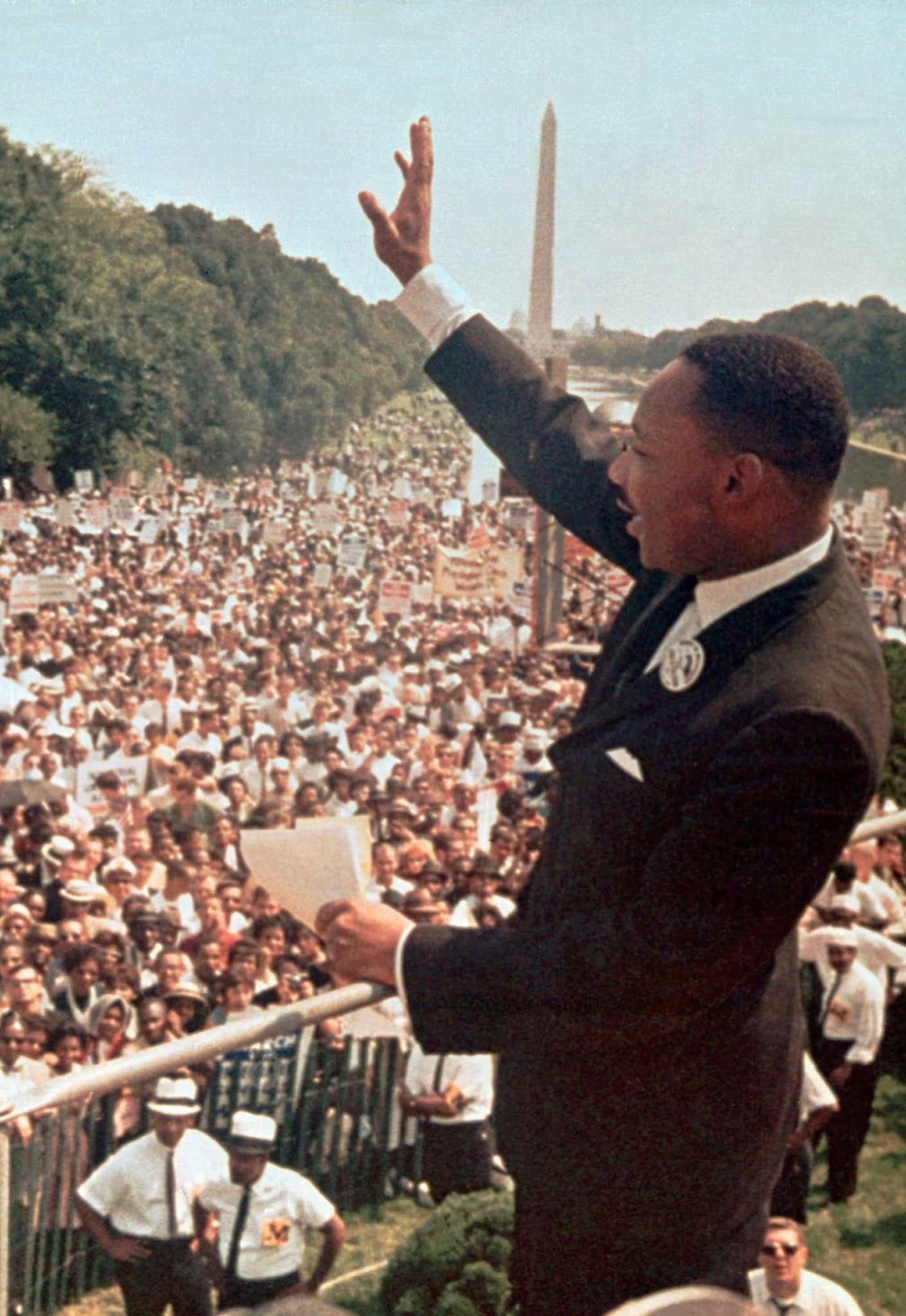

From the stifling protocols of "identity politics" to class-based ideology and the "war on terror", he views these "antagonistic solidarities" not as hard-wired elements of human culture. Rather they are artificial - and distinctly fragile - creations belied by the ample evidence that, in most times and places, people of various sorts have got along in amity and harmony. For much of history, the agreement to differ has proved more attractive than the zealot's exhortations to mortal struggle against a demonised enemy - from the Polish Jesuit in 1592 who thought his Protestant rivals "good neighbours and brethren" to Martin Luther King and Nelson Mandela's assertion of the unity of "the entire human race".

So far, so uplifting - and, perhaps, so bland. Touchingly, Cannadine calls in evidence the versified sentiments of both Maya Angelou ("we are more alike, my friends/ Than we are unalike") and Rudyard Kipling, who maintained that exposure to a wider world would make "nice people, like Us" realise that "We" are "only a sort of They". Who could possibly object to this Coca-Cola universalism? The answer lies among the intellectual partisans of "sheep and goats" separation: the politicians, thinkers and priests who have preached the myths of eternal division - and, above all, among binary-minded historians themselves. Inside Cannadine's broad appeal to "shared humanity" against all sectarians and dogmatists lies a narrower, sharper book about what in his view has gone wrong with the practice of history. Cosy bromides aside, he aims to clean up his own professional backyard.

In Monty Python-esque terms, the "splittists" have made too much of the running for his taste. Now-discredited racists and nationalists were followed by class-obsessed Marxists (down but not out), feminists - still in the ring - and the post-Cold War (and post-9/11) followers of Samuel Huntington, who misread the "clash of civilisations" thesis to seek a formulaic recipe for the rise and fall of cultures. All have insisted that their own cherished "all-pervasive polarity" - Christians vs Muslims, bourgeois vs proletarians, men vs women, the West vs the Rest - will open history's lock and reveal its innermost secrets.

Like a "triumphant pumpkin" or "victorious turnip" at a village fete, one-cause-fits-all historians will brandish their own pet dichotomy as the rosette-winning formula that supersedes all others: from Edward Gibbon with his overwrought oppositions of pagans and Christians, Romans and "barbarians", through to the once-revered "scientific racists" who built palaces of nonsense atop their own flimsy prejudices. The Undivided Past succeeds best as a Swiftian treatise on the ignorance of the learned, and the follies of the wise.

Cannadine has plenty of debunking fun with these collapse-prone chasms of the past, and its us-and-them interpreters. However, his own rhetoric can lack finesse, with too many clunky adjectival pile-ups, over-strenuous repetitions and glib alliterations that probably sounded better in the lecture hall (the book originated as the Trevelyan Lectures at Cambridge). The heavy podium style tends to steer what is a very personal project - born out of his exasperation at the ideological and academic denial of empathy and affinity - into a stern, cross survey of the error-strewn literature. Moreover, the topic-by-topic approach leads to some bizarre assymetries. He tacitly fuses, or at least confuses, annoying fads in the liberal academy and incitements to genocidal hatred. Heinrich Himmler and Germaine Greer might both peddle "simplistic" accounts of human division as a motor of history, but they don't really belong in the same polemical breath.

Ever since the Enlightenment, the "universal" writer or historian whose Olympian worldview overrides all blinkered, parochial interests has often turned out to be the privileged chap in an elite institutional club - a caveat that Cannadine, now at Princeton but first a Cambridge protégé of JH Plumb (as were Simon Schama, Niall Ferguson, Norman Stone and so many other leading historians), could have addressed more openly.

His book's combative stance also means that its own ideal of amicable commerce and co-existence between peoples passes with only superficial examination. It could be argued that the pluralistic harmony of "transcultural flows and movements" that he espouses will always depend on the lurking presence of some kind of imperial power, even if the underpinning of this "global cosmopolitanism" today resides more in corporate capital than in brute military force.

Yet, while the fetishism of a single, adversarial identity still derails the study of history as much as the practice of politics, The Undivided Past should earn applause. If we accept that "identities are not like hats, which can only be worn one at a time", then we owe it to people in the past to credit them with at least as much "nuance" (a favourite Cannadine term) and inner complexity as us. The chauvinists, the xenophobes, the demagogues, have never, as he shows, spoken for all - or even for most. So, the next time some tub-thumping loudmouth proclaims the timeless truth of a binary divide - between, say, "Britain" and "Europe", to cite one topical addendum to Cannadine's list of false polarities - throw this book at them.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks