Three thrilling collections of folk and fairytales from around the world

The rewards of these collections are irresistible, and as the autumn nights draw longer, why not pause, and partake of an age-old tradition?

Autumn is the season for stories.

The nights begin early and last long. Especially in Scotland and further north in that other land of legends and fairy tales, Norway. Candles help. So do stories. This autumn brings tales of old, and not so old, in three beguiling collections that are both a showcase of the enduring fascination with tales of the marvellous and strange and a celebration of those scholars who continue to research the realm of folklore.

They unearth gems, and further our understanding of the stories and storytellers’ place in the cultural history of their respective countries and, more broadly, in the universal human need to tell and listen to stories. Translator Jack Zipes brings us the Brothers Grimm, but not entirely as we know them; Marina Warner introduces us to a lesser-known side of that acutely political thinker, activist, memoirist and once bestselling novelist Naomi Mitchison, who chose Scotland as her home; Malcolm C. Lyons and Robert Irwin, who collaborated on the Penguin Classics edition of Arabian Nights, bring the fruits of a long-lost manuscript, discovered in a library in Istanbul, the earliest known collection of Arabic stories – no Snow Queens or forest enchantments here, butthe lure of the souk, the heat of the desert, and dangerous women of a different hue. Three different worlds to enter: three doors, three keys.

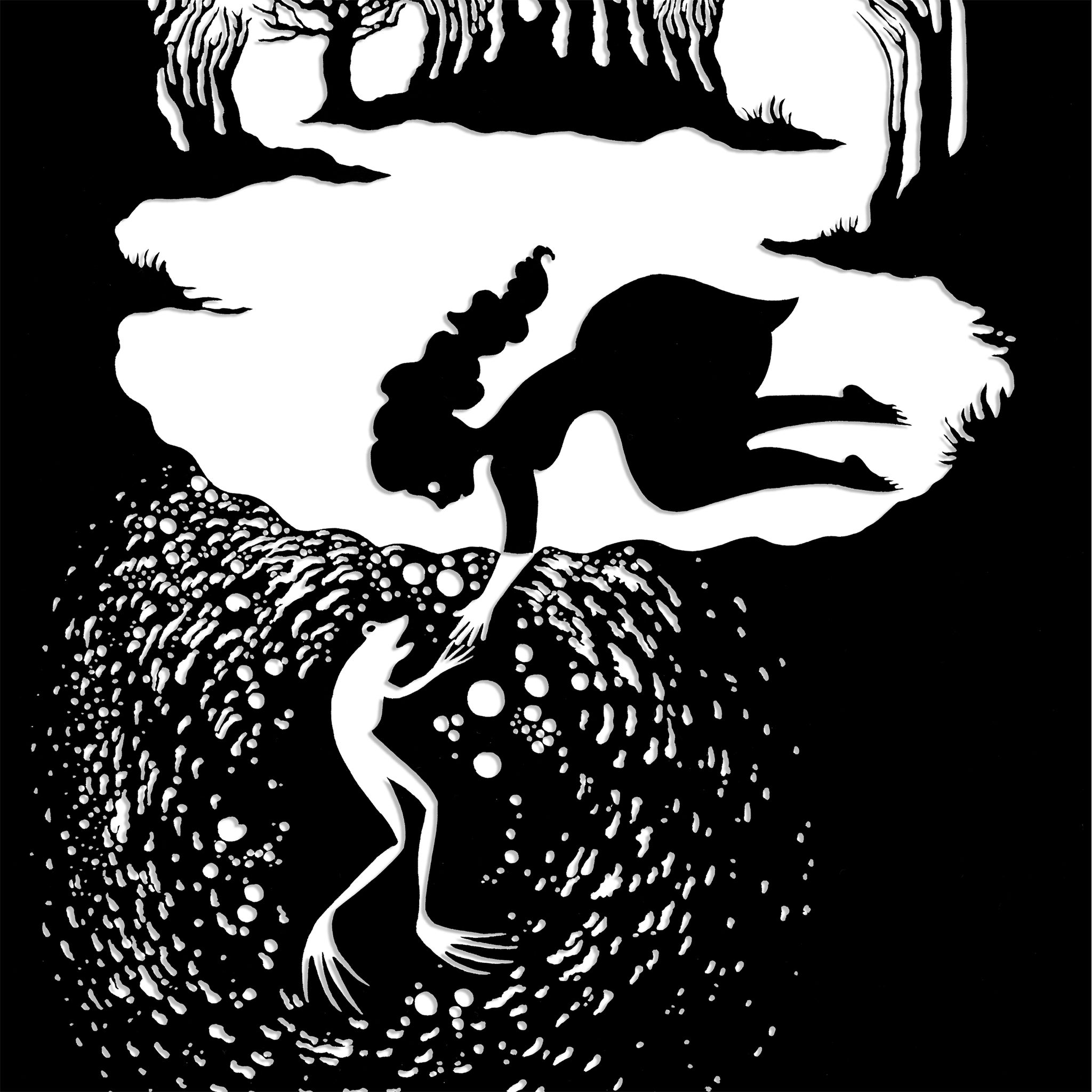

There is a mysterious doorway in Aberdeen’s Art Gallery. You could almost miss it. Opposite the Vuillard and beside the Braque, a dark passage leads to a series of illustrations by Walter Crane. His Frog Prince is emblematic of the Arts and Crafts movement: rich in colour and detail, the expressions of the King’s wolfhound and hawk, the fabrics of the princess’s gowns, the table-cloth and carriage enhance the telling.

This optimistic tale, Zipes notes, always opened Grimms’ two-volume Children’s and Household Tales, from the first editions of 1812 and 1815, to what came to be regarded as the “definitive” edition, the 1857 one familiar to readers today. In fact, that seventh incarnation, Wilhelm having rigorously rendered the tales more palatable and child-friendly to suit the burgeoning middle-class (brother Jacob would have preferred less “refining”), is at quite a remove from the original, translated now in its entirety for the first time.

These tales retain the “pungent and naïve flavor of the oral tradition” and are indeed remarkable narratives for being “so blunt and unpretentious”. Zipes’s introduction to the leading philologists of the day’s “passion for recovering the ‘true’ nature of the German people through their so-called natural Poesie” is illuminating. Inspired as students by jurisprudence professor Friedrich Carl von Savigny to regard “language as the ultimate bond that united the German people”, their quest for the roots of “German nature”, all the more pertinent in Napoleon’s heyday, sent the brothers to ancient literatures, listening out for echoes of Nordic and Scottish legends, imbibing the Italian collections of Straparola and Basile, those of Perrault and Mlle de la Force, noting shared attributes with the ancient Greek of their classical education. They had a “profound belief that their tales were … thousands of years old and part of a vast Indo-European oral tradition”. Encountering tales in their studies, the brothers were also indebted to storytellers of their own time, from circles of middle-class and aristocratic ladies, soldiers discharged from wars exchanging stories for clothing or money, hospital patients, writers and artists, teachers, ministers, and one tailor’s wife in particular, Dorothee Viehmann.

This is the uncut Brothers Grimm: shocking, funny, and at times downright weird. Nothing is taboo. Some original versions contain surprising twists: Rapunzel is made pregnant by her visiting prince; a king harbours incestuous thoughts towards his daughter; it is not stepmothers who wish the extra mouths at the table ill, oh no, it is mothers themselves; and there are tales of Death and of Christian misunderstandings. “These tales were not told for children”, we are reminded, however enthralled my own godchildren would be by “Hans the Hedgehog” or “The Wren and the Bear”.

Nor for children the fascinating tales and ballads by Naomi Mitchison in The Fourth Pig, first published in 1936, and now reissued in the ‘Oddly Modern Fairy Tales’ series. Who better to introduce her than Marina Warner, who gets under the skin of the prolific, but now too often forgotten, left-wing intellectual. Hers, Warner notes, was a “struggle between the good citizen and the wild girl, the nurse and the sorceress”. A groundswell of unease and fear characterises a collection written in the knowledge of the Spanish Civil War and with a foreboding of Fascism’s reach.

The Fourth Pig is brother to the obliterated first three and he knows no peace: “… I cannot remember…the innocence of the world before thought came and memory and foresight, and knowledge of the Wolf”. A cormorant landing on St Paul’s is a harbinger of war. Feminism melts to a longing for “rates and rent and gas cookers, and … broccoli plants for bedding” in Mitchison’s amusing version of “The Snow Maiden” while the centrepiece is a delightful play, “Kate Crackernuts”, also for children, based on an Orcadian legend collected by Andrew Lang, with echoes of Christina Rossetti.

Differently adult are the long-lost tales rediscovered in Istanbul by a French Orientalist, translated flowingly here from the Arabic by Lyons. Princes and slave-girls, white stallions and gazelles, wiliness, wisdom, excess, eroticism, rags to riches, brutality, compassion or lack thereof, these tales are purportedly over a millennium old, precursors to The Arabian Nights. They offer a gateway to a different world of language and ideas, florid, wildly descriptive, and are a powerful reminder of the human need for story. In “The Story of the Six Men” the king offers a reward to “anyone who has something wonderful to tell”.

The rewards of these collections are irresistible. As the autumn nights draw longer, why not pause, and partake of an age-old tradition. Once upon a time…

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments