Classical review: Prom 41 - One man, two conductors – a musical comedy

Russian maestro Valery Gergiev performs erratically, but empty seats are the evening’s real surprise

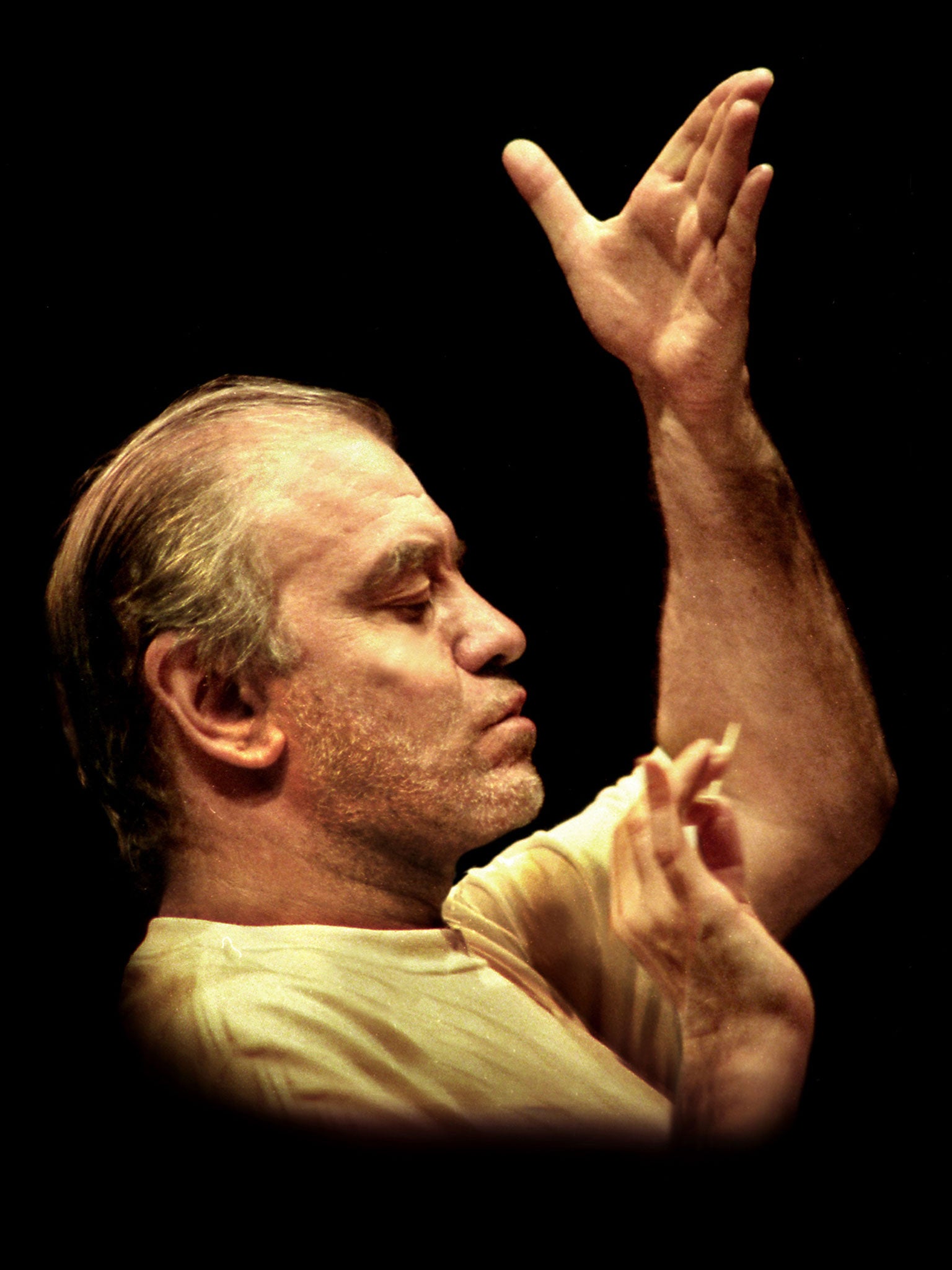

The conductor Valery Gergiev is predictable only in his unpredictability.

At his best, those hulking shoulders and humming-bird hands – 10 digits each, or so it seems as the silky layers of the London Symphony Orchestra’s wind, brass and strings merge and separate – produce a kind of magic: volatile, mercurial, heart-stopping. At his worst, distractedly flipping the pages of a score, the tension that is produced on stage is less that of performance than that of public sight-reading.

The LSO are too proud and polished an ensemble to allow these infelicities to muddy their attack. Their polish comes from the impeccable technique of each player and the radiant blend of each section. Their pride is more complex: a combination of an awareness of their standing as one of the world’s foremost orchestras and the passion that every musician, from amateur madrigalist to international soloist, brings to animating the dots on a stave.

Prom 41 saw both Gergievs: one lacklustre and disorganised, the LSO section leaders working overtime to compensate, the other brilliant and dynamic. Borodin’s under-loved Second Symphony, so delicate and wistful in Mark Elder’s interpretation, was all bite, bravado and heel-of-the-bow muscularity, the horns a sweet, melancholy afterglow to the tumult. The plush orchestral accompaniment to Daniil Trifonov’s performance of Glazunov’s Second Piano Concerto lacked definition, though all ears were on the pianist’s fusillade of double octaves and the glittering elegance of his cadence.

Trifonov produced a smallish but exquisite sound, maybe reserving his energy for the blister and bluster of his encore, Guido Agosti’s acrobatic arrangement of the danse infernale from Stravinsky’s Firebird.

In Sofia Gubaidulina’s The Rider on the White Horse, Gergiev finally engaged with his material and his players to sensational effect. The convulsions of brass, magnesium-white bowed percussion, apocalyptic bass drums, shrieking organ and skittering harpsichord describe a conflagration of merciless violence. Gubaidulina is the most dyspeptic of spiritual composers, a kind of anti-Messaien, making even redemption sound arduous and painful.

Ravel’s orchestration of Mussorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition, so much more French than Russian in its urbane theatricality and wine-rich instrumentation, completed the programme, the orchestra on unbeatable form, Gergiev now free to play with a score that is thoroughly under his skin.

Odd, though, to see the Albert Hall only three-quarters full for this work, this conductor, this orchestra. But until Gergiev joins Anna Netrebko in making some statement against Russia’s treatment of the LGBT community, I suspect his audience will continue to shrink.

Baritone Jacques Imbrailo’s voice has grown richer and stronger since the 2010 premiere of Michael Grandage’s Glyndebourne production of Billy Budd (East Sussex *****). With maturity comes sophistication, yet Imbrailo’s Billy is as honest and open and trusting as ever, and his final lilting lament more devastating.

Much like Peter Grimes, the opera is a masterpiece of moral ambivalence. With the casting of Brindley Sherratt as Claggart, more sinister for his stillness and self-control, and Mark Padmore as Captain Vere, another facet of cruelty in the work is revealed. Though Claggart’s false accusation of mutiny is the lie that causes Billy’s death, a far worse lie is sung by Vere in the Drumhead Court (“It is not his trial, it is mine”). The study of Plutarch, the cultivation of honour and a good reputation are revealed as worthless when Vere fails to intervene. As Billy is hanged, with his friends Dansker (Jeremy White), Red Whiskers (Alasdair Elliott), Donald (John Moore) and Novice’s Friend (Duncan Rock) frozen in an agonised Géricault tableau, and the men growl in rage like chained dogs, Vere’s authority is destroyed.

Faultlessly eloquent lighting (Paule Constable), design (Christopher Oram), conducting (Andrew Davis), playing (London Philharmonic Orchestra) and ensemble singing combine in a performance that makes this all-male opera transcend its specifics.

‘Billy Budd’ (glyndebourne.org) to 25 Aug and at the BBC Proms (bbc.org.uk/proms), 27 Aug

Critic's Choice

Jane Manning, the doyenne of contemporary music, celebrates her 75th birthday at the Tête à Tête Festival with an afternoon of extended vocal technique and the newest of new music, Riverside Studios, London (Sunday). Harpsichord virtuoso Christophe Rousset plays music from Frescobaldi to Royer on five extraordinary instruments from St Cecilia’s Hall, Edinburgh (Thurs and Fri).

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks