Meet 96-year-old Frederick Wiseman, the best American filmmaker you’ve (probably) never heard of

There are few filmmakers around as insightful, prolific, and profound as Frederick Wiseman, writes Louis Chilton. But his documentaries have always been difficult to watch in the UK – until now

When we talk about the Great American Filmmakers, there are some names that simply demand to be mentioned. Names like Martin Scorsese, Stanley Kubrick, or David Lynch: those artists whose coruscating command over the medium has made them globally, lastingly famous. And then there are names like Frederick Wiseman.

It’s no mystery why the prolific 96-year-old filmmaker has never had even a morsel of the mainstream recognition afforded to his peers, though many of those who have watched his output agree that his place in the canon is undeniable. For one thing, he almost exclusively makes documentaries, a mode of filmmaking that’s hardly packing out the multiplexes. Even within the world of documentaries, though, he remains a more obscure figure than, say, Ken Burns, Michael Moore, or even Asif Kapadia.

Partly this is down to the work itself: his films are subtle, intricate pieces, which demand deep engagement to really unpick. They are often long, sometimes as long as four or six hours. Many are named bluntly for their subject matter, with titles such as Hospital, Racetrack, Multi-Handicapped, Domestic Violence or State Legislature; said subject matter is also usually weighty, and (on the surface, at least) forebodingly sombre. Mostly, however, Wiseman is underappreciated in the UK simply because his films have been so very hard to see – until now.

In the US, Wiseman has for decades self-distributed his work via his company Zipporah Film, with his filmography also available on the free-to-use American library streaming service Kanopy. Now, for the first time, a significant part of Wiseman’s brilliant, essential oeuvre is available to stream in the UK, via a new collection on the BFI Player. Nine of the director’s films are included, while five films are also being released in a blu-ray boxset.

The first of these, Wiseman’s 1967 debut Titicut Follies, is also his most discussed project. Filmed in what was then called Bridgewater State Hospital for the Criminally Insane, Follies is a damning, unflinching look at the Massachusetts facility’s (mis)treatment of its inmates – a candid, harrowing and in flashes grimly funny peek behind the curtain of the sort of unevolved psychiatric institution that inspired Ken Kesey’s One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest just a few years prior. (When Cuckoo’s Nest was adapted into a film in the mid-Seventies, Follies was repeatedly screened for the cast in preparation.) The documentary drew complaints from Bridgewater and the Massachusetts government – ostensibly over the patients’ inability to consent to being filmed, but argued by Wiseman and others to be politically motivated – that led to the film being banned for over two decades.

Many of the hallmarks of Wiseman’s style were visible here from the get-go: there is a complete absence of captions, voiceovers, talking-head interviews or explanatory context. His films simply drop you in a location and leave you to figure out what you’re seeing, and why you’re seeing it. His messages are conveyed through editing and framing, both precise and inventive from the very first film. Wiseman has consistently disputed the idea that he is simply presenting the world as it appears: there is always, of course, some degree of subjectivity in the filming and assembling of any documentary. But as much as any documentary can, a Wiseman film feels almost impossibly fly-on-the-wall, as if you are witnessing the real world first hand.

Titicut Follies also explored many of the themes that Wiseman would return to again and again, throughout his 46-film career: institutions and the way people interface with them; care of the unwell; violence, in all its forms; authority and the abuse thereof. If there is some ethical doubt over the inmates’ ability to consent to the documentary – permission was granted for many by the hospital superintendent, acting as their legal guardian – then there was also undoubtedly a benefit in exposing their terrible experiences to the world.

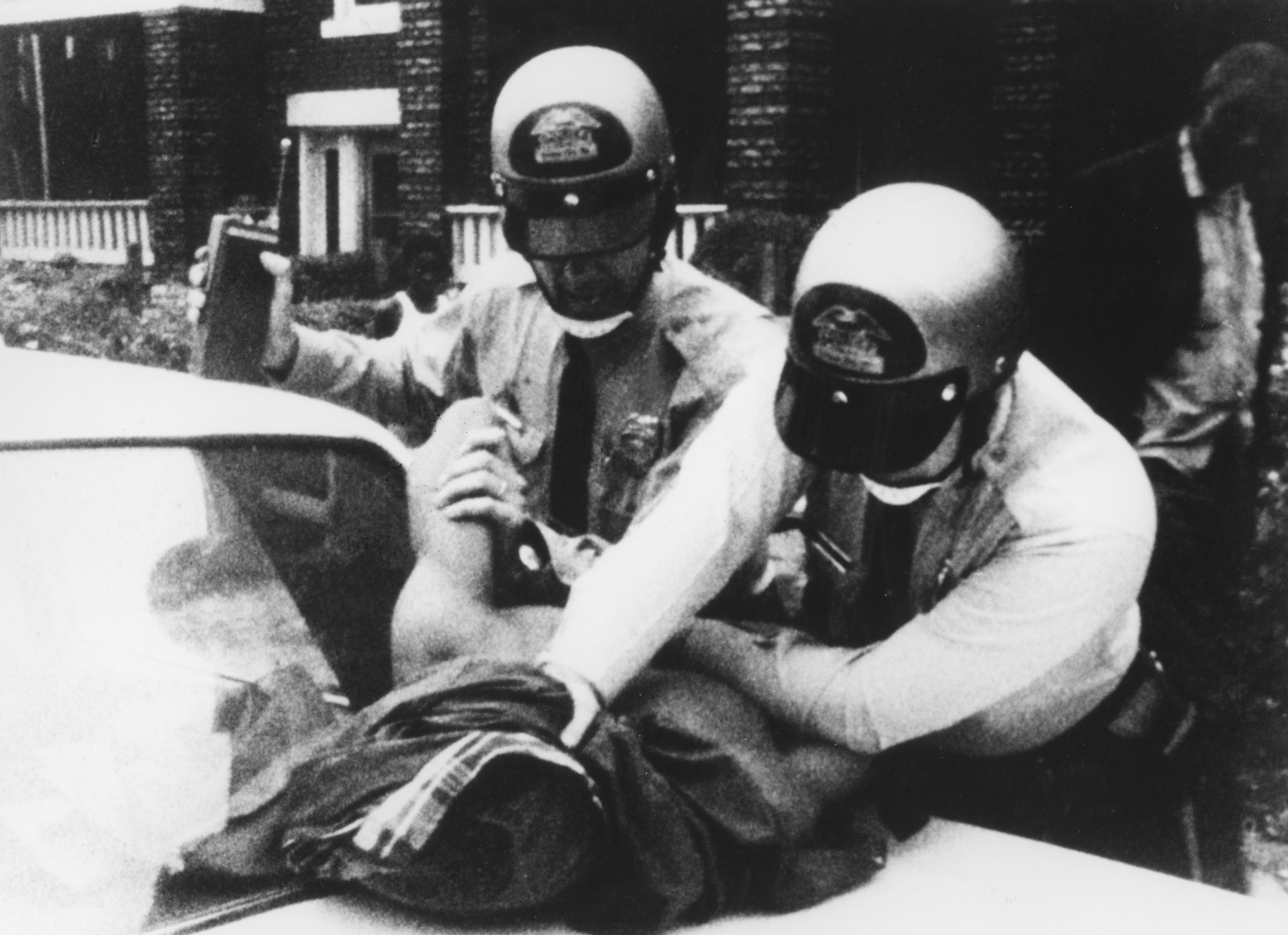

It’s the sort of quandary that surfaces a few times watching Wiseman’s films, notably in 1969’s Law and Order, which followed members of the Kansas City Police Department. In one scene, officers violently place a woman in a chokehold, rendering her unable to breathe, and then deny doing so just a minute later. Wiseman’s camera captures it all, without intervention. If something is jarring about this passive spectatorship, then it’s a restraint that proved in many ways justified: the film has become a lasting document of the brutality endemic within the American police.

Shortly after Law and Order’s release, Wiseman denied that the film was anti-cop, stating that he had realised while filming that his negative stereotypes of the police were “far from the truth”. Watch the film, and it’s hard to believe this wasn’t a complete lie. Even outside of the violence, Law and Order paints a picture of the police as routinely antagonistic, inefficient and abjectly uninterested in actually helping its citizenry.

Not all of Wiseman’s films are as eviscerating of their subjects, though some are: 1974’s Primate takes a sickening look at scientific research on animals, while Juvenile Court (1973) is a scathing exploration of the juvenile court system. Others, such as High School (1968) and Public Housing (1997), are critical but nuanced studies of particular institutions, and the way that those institutions intersect with wider systems and ideologies. The seeming inscrutability of Wiseman’s style leaves much of his work open to interpretation: you are presented with footage, and not told how to necessarily feel about it.

As he got older, Wiseman’s films grew longer, and also, broadly speaking, less angry: later efforts such as National Gallery (2014), Ex Libris: The New York Public Library (2017), and Menus-Plaisirs – Les Troisgros (his latest and seemingly final film, set within a Michelin-starred restaurant in France), are more sympathetic towards their subjects.

Wiseman’s approach to filmmaking, though, remained the same over the years. First, he would decide the subject of his film (initially, he chose buildings or institutions, but later films sometimes expanded to cover entire towns or communities). Then he would film there for a period of weeks, capturing hundreds of hours of footage, to be edited slowly and carefully for as long as a year. He would never be behind the camera himself, preferring instead to hold the sound equipment. This, he explained, allowed him to better see what was out of frame, to constantly look for the most interesting tangent to follow. He was canny too with information networks, relying on tip-offs to direct him to eccentric and revealing meetings, events and people.

It is this capacity for the unexpected that ultimately makes Wiseman’s cinema so fascinating. In many of his films, there are sudden and startling detours that he is all too happy to stay with. The incredible Hospital (1970) features a long sequence of an art student having a bad trip on psychedelics – we watch him insist that he’s going to die (while doctors patiently reiterate that he definitely won’t), then vomit everywhere, then question aloud his entire history of life decisions. Boxing Gym (2010), a relatively minor work set in a Texan boxing gym, features a fascinatingly matter-of-fact conversation about the then-recent Virginia Tech shooting with a gym-goer who knew one of the victims. Central Park (1990) includes a segment in which we watch Francis Ford Coppola directing a movie (his segment of the triptych New York Stories), because he happened to be filming that day within the perimeter of Wiseman’s hunting ground.

Welfare (1975) ends with perhaps Wiseman’s most incredible sequence, in which a man, beaten down by the welfare bureaucracy’s refusal to help him, goes on an erudite, peculiar rant about the injustice of it all. Partway through the speech, he sits down, and he stops addressing the welfare officer, and his speech transforms into a prayer, a despairing address to God. It’s a stunning, poetic, tragic vignette, not just a sorry indictment of the welfare system’s shortcomings, but an incredible reminder of just how much complicated, meaningful interiority exists within every person. Wiseman’s films are about systems and institutions, but they are also about people, in a way that is absolutely profound.

In case it isn’t obvious, it’s hard to really condense Wiseman’s filmography into a summary like this; his films are the stuff of life, and they contain life in all its labyrinthine vastness. Even these new releases – and the recent retrospectives at London’s BFI Southbank and ICA cinemas – only touch upon parts of the director’s rich, decades-long project; there are dozens more films that remain more or less inaccessible in the UK today. But the renewed interest – and, perhaps, the Academy’s decision to award him an honorary Oscar in 2016 – is a sign that the world is starting to catch up with Wiseman’s fiercely humanistic genius. He is a major filmmaker, and like all major filmmakers, he makes films that demand to be seen.

‘Cinema Expanded: The Films of Frederick Wiseman’ is out on BFI Blu-ray, Apple TV and Amazon Prime now

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks