The South Park movie at 20: The censorship satire Hollywood thought was doomed from the start

As ‘South Park: Bigger, Longer and Uncut’ turns 20, Al Horner looks at how Trey Parker and Matt Stone found success with a film they thought would mark the end of their careers

As El Paso counted its dead, Walmart took action.

On 3 August this year, a white supremacist entered a Texan branch of the US grocery chain and began gunning down shoppers, killing 22 and maiming 24 in a racially motivated act of domestic terrorism inspired by March’s Christchurch mosque shooting. The attack came less than a month after another mass shooting in a Walmart store, in Mississippi, where a disgruntled employee killed two and wounded an officer. A strong response was needed, and on 9 August, the company found one. Employees at Walmarts across the country were directed to take down displays advertising supposedly violent video games.

As signs for shoot-’em-ups were hurried out of public view, aisles of firearms and ammunition were left untroubled by the company. Walmart, which claims to sell one out of every 50 guns sold in America each year, and one out of every five bullets, had put their best guys on the job, and seemingly concluded that firearms weren’t at fault for all the lives lost in their stores. Fortnite was to blame.

Somewhere, Trey Parker and Matt Stone probably sighed, wondering when the lines became so blurred between real life and their imaginations. After all, a popular youth culture product being blamed for America’s ills by adults who’d rather scapegoat than confront the root of the problem? That’s pretty much the exact plot of South Park: Bigger, Longer and Uncut, their adult animation’s first and so far only foray onto the big screen, released in the UK 20 years ago today.

The film’s meta-narrative made knowing winks at the controversy that followed the show’s first few seasons. After quickly becoming household names after South Park’s first season in 1997, the show’s creators Parker and Stone were accused by conservative and Christian groups of corrupting American children with the show’s bad language and risque, taboo content. The conservative advocacy group Parents Television Council called it a “curdled, malodorous black hole of Comedy Central vomit” that “shouldn’t have been made”. This didn’t come as much of a shock to Parker and Stone: by the end of the show’s first run, it had depicted an alien anal probe, a boxing fight between Satan and Jesus and introduced a singing, talking turd called Mr Hankey, intent on saving Christmas, after all.

The narrative of their hotly anticipated South Park film therefore featured an almighty kerfuffle about a new movie from Cartman and co’s favourite comedians, Canadians Terrence and Phillip. The show’s kid protagonists all love the film, which includes a song called “Uncle F**ka” and a whole lot of farting. The town’s parents, however, quickly decide that Terrence and Phillip are to blame for society’s supposedly declining morals. It spirals into a war between America and Canada: a conflict that Stan, Kyle and Cartman soon find themselves immersed in (the group’s fourth member, Kenny, is otherwise engaged being dead, trapped in hell with Satan and his new romantic partner, Saddam Hussain).

The war on screen was only slightly less brutal than the one behind the scenes, between Stone, Parker and the studio, Paramount. During the show’s first season, as South Park fever spread across America, Cartman dolls flew off the shelves and Kenny posters started covering walls in college dorms everywhere, and Paramount began to plead with the pair to make a movie. It’d be a giant money-spinner, they insisted – not just in terms of box office, but in merchandise sales, which were already booming. Such was their certainty, they reportedly offered a seven-figure cash bonus to the duo to make South Park: The Movie.

Paramount understood the show’s money-making potential, but not the show itself, it quickly transpired. Between the show’s first season and the movie coming out, South Park’s ratings had dropped. Critics began to suggest the series’ time was up, that it had been a fad. This, Stone said at the time, was “bulls**t”, pointing out: “That was when we were on the cover of Rolling Stone, we were on the cover of Newsweek and we had a huge article in Time. We were the thing for that month, right? And that kind of press buys you numbers. There were a lot of people watching the show who probably had no business seeing it. It still gets great ratings.”

Nonetheless, critics predicted South Park’s imminent demise. Paramount had missed their chance to capitalise on the show’s initial success. With Star Wars: The Phantom Menace and Austin Powers: The Spy Who Shagged Me, their competition at the summer box office, they were staring down the barrel of a commercial flop, detractors claimed.

The pair were angry, and poured their anger into South Park: The Movie. It was “the most stressed out I’ve ever been”, Parker told Playboy in 2000.

“I really felt it was our suicide note,” added Stone. “We felt like, they’re going to cancel the show after this movie comes out, but we’re going to f***ing do it our way. It’ll be a big middle finger to Hollywood, and then everyone will hate us and we’ll go back to Colorado.”

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 day

New subscribers only. £9.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled.

ADVERTISEMENT. If you sign up to this service we will earn commission. This revenue helps to fund journalism across The Independent.

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 day

New subscribers only. £9.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled.

ADVERTISEMENT. If you sign up to this service we will earn commission. This revenue helps to fund journalism across The Independent.

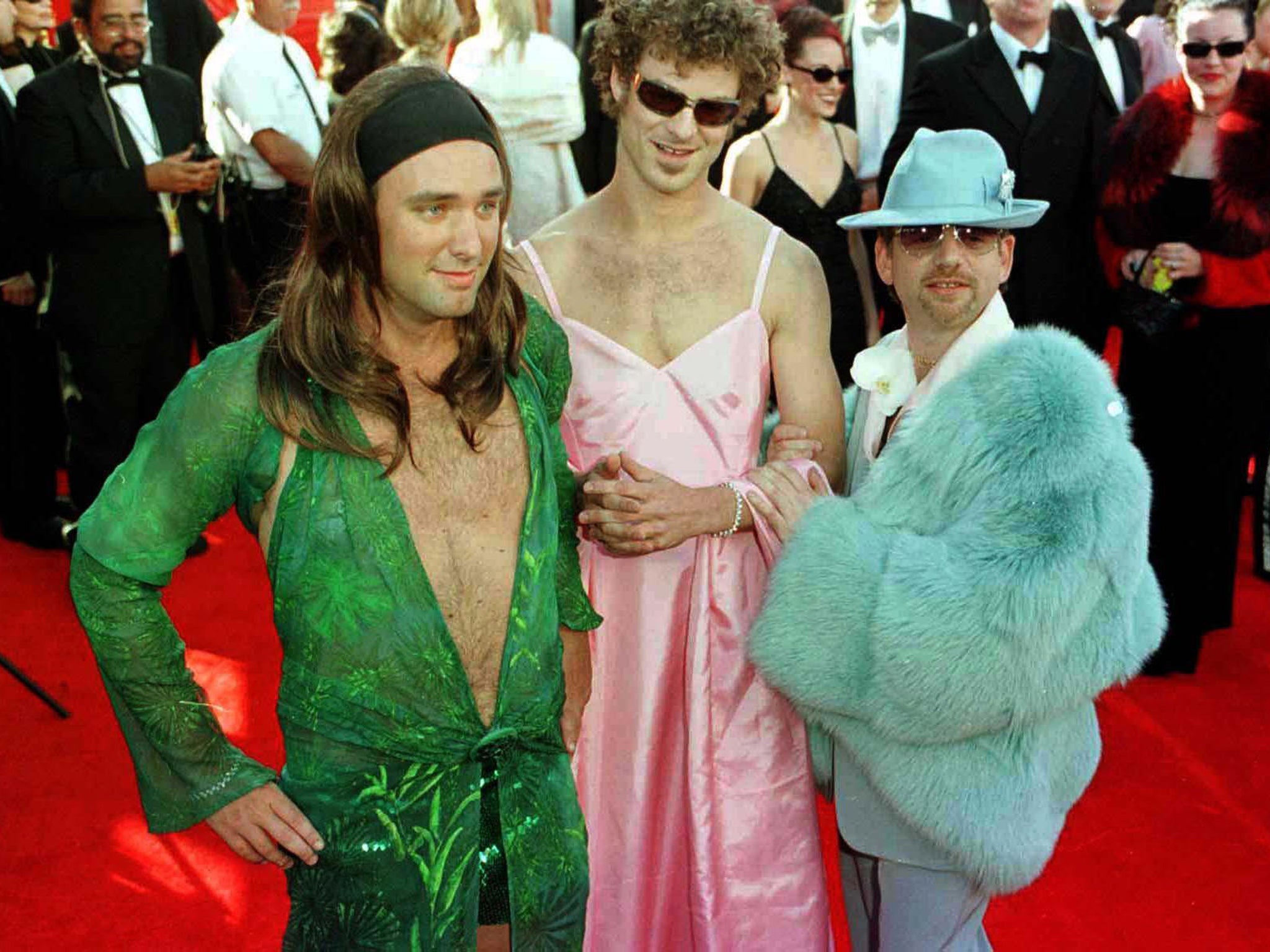

A panicked Paramount tried to market the film to the broadest possible audience, in the most un-South Park of ways. “The studio did everything they could to beat us down and beat the spirit out of the movie,” Stone is quoted as saying. A music video was made for MTV that Stone and Parker detested. One trailer described the film as the “laughiest movie of the summer”. When the duo were sent that promo for their approval, they snapped the VHS in half and mailed it straight back. “It was war,” Parker told Playboy. “They were saying, ‘Are you telling us how to do our job?’ And I was going, ‘Yes, because you’re f***ing stupid and you don’t know what you’re doing.’”

Somehow, despite it all, the brilliant South Park: Bigger, Longer and Uncut was a huge success. Critics loved it – The New York Times called it “a scathing social parable in which desperate, paranoid grown-ups who long for an impossibly sanitised environment go collectively crazy to the point that they’re willing to bring on World War III. And what are they so afraid of? Just some dumb off-colour humour about bodily functions.” The Independent was similarly won over, calling it “a non-stop barrage of toilet jokes, rude words and wired pop-culture piss-takes”.

It made $83m worldwide against a budget of $21m, although that might only be half the story: US newspapers were full of reports of young teens buying tickets for PG-rated Will Smith vehicle Wild Wild West, then sneaking into screens showing the R-rated South Park film instead. The movie’s success did little to patch things up between Stone, Parker and Paramount though. One of the reasons a second South Park movie has never materialised is perhaps because Paramount still reportedly retain rights to further South Park films, and neither party wants to work with the other again, such was the struggle of Bigger, Longer and Uncut.

South Park is expected to return for its 23rd season later this year. Who knows if the summer’s spate of mass shootings, and Walmart’s strange response to the killings in El Paso, will be in Parker and Stone’s satirical crosshairs? It wouldn’t be the first time, if so: their 19th-season finale, “PC Principal Final Justice”, lampooned America’s gun control debate by having Cartman and his mum pull firearms on each other in an argument over his bedtime, while Walmart has come under fire from the show before, in 2004’s “Something Wall-Mart This Way Comes”. Walmart’s response to the El Paso terror attack is exactly the type of warped thinking Parker and Stone have loved exposing since South Park began, as it struggles to remain relevant in the time of Trump.

“It’s tricky now because satire has become reality,” Parker told ABC Australia in 2017 as the show returned for its first season since the 2016 election, tapping into a deeper question for comedy in 2019. How can satire survive in a society stranger than could be dreamt up in any parody? Twenty years after the oddly still-resonant South Park: Bigger, Longer and Uncut, it’s a problem no one seems to have an answer to. Not Parker, not Stone – not even Brian Boitano.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks