The shadow cast by Ealing comedies is no laughing matter

Kind Hearts and Coronets, Whisky Galore! and the rest are a malign influence on today's cinema, says Geoffrey Macnab

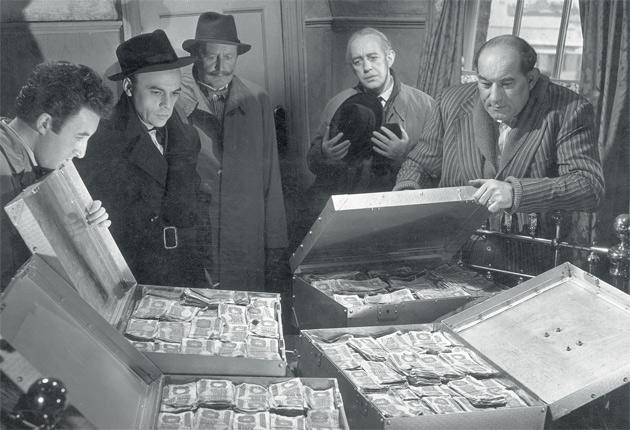

It's the 80th anniversary of Ealing Studios this year. To mark the event, restored versions of some of Ealing's greatest comedies are being released (yet again) in British cinemas. Kind Hearts and Coronets, The Lavender Hill Mob and Whisky Galore! are all being dusted down. British cinema-goers can, yet again, enjoy the murderous antics of Dennis Price killing off his relatives; the exhilarating sight of Alec Guinness's timorous bank clerk running amok with stolen gold-plated Eiffel Towers, and the cunning tricks of Scottish islanders who hide 50,000 cases of whisky.

Whenever the Ealing comedies of the late 1940s and early 1950s re-emerge, a mood of nostalgia invariably overcomes commentators and critics. Despite the subversive edge existing in so many of the films, their celebration of community, consensus and mild but lovable eccentricity is applauded. They are seen as representing an idealised Britain where small-timers invariably thwart big, bad bureaucrats and where tolerance, humour and benevolence rule. Ealing was the "Studio with the Team Spirit," the film industry equivalent of the family business. It self-consciously set out to make movies "projecting Britain and the British character."

Ealing stood for continuity and decency (both qualities generally in short supply in the British film industry.) As film historian Charles Barr wrote, "in a business notorious for size and instability, for a rapid turnover of money, ideas and people, Ealing succeeded in keeping itself small and stable."

The irony is that these modestly budgeted films made in West London under the guidance of studio boss (and benevolent patriarch) Michael Balcon have come to act as a huge millstone around the necks of future generations of British film-makers. For any Brit making a low-ish budget, character-driven, ensemble comedy, Ealing is still the immediate and only point of reference. And very infrequently do film-makers come anywhere close to emulating the greatest Ealing comedies – often they're chastised for having even tried.

Last month, when Father Ted writer Graham Linehan appeared on BBC Radio 4's Today programme to discuss his forthcoming stage version of Ealing classic The Ladykillers, he was startled by how aggressively he was questioned (he complained later about being "ambushed"). Linehan was asked if he should be "turning a perfect film into a play". The assumption was that he was bound to bowdlerise and diminish the original film.

Linehan's experience at the hands of an unsympathetic interviewer underlines what happens to anyone who has the temerity to tamper with the Ealing brand.

Ealing was certainly the prism through which the work of the great Scottish director Bill Forsyth was viewed in the 1980s. Gregory's Girl (1981) and Local Hero (1983) were routinely described as Ealing-style comedies. When Forsyth's films were praised for being in "the tradition of Ealing," it was a double-edged compliment. Critics weren't prepared to accept that Forsyth had a vision of his own.

During the 1990s, films like The Full Monty (1997), about redundant steel-workers who become male strippers, and Brassed Off (1996), the story of a brass band in a South Yorkshire mining village whose colliery is threatened with closure, were likewise routinely bracketed with Ealing. Both combined humour with a political subtext. Both were ensemble pieces foregrounding character actors rather than star turns, and camaraderie rather than individualism. By a process of crude critical reductionism, that meant that they had to be described as being "in the spirit of Ealing."

Even today, Ealing remains a convenient point of reference for categorising new British films of all genres. Joe Cornish's recent sci-fi movie Attack the Block (2011), about kids from a council estate pitted against aliens, was described by one reviewer as harking back "to the heyday of Ealing comedy", when "classes and nations" united to resist a common enemy. Nigel Cole's Made in Dagenham (2010), about a group of female factory workers fighting for equal wages in the late 1960s, was described as "the type of film that could have been made by Ealing Studios back in the 1950s" (Cole's earlier film, Calendar Girls (2006), about Women's Institute members stripping for a charity calendar, was likewise described by many critics as being a near-Ealing-facsimile).

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 day

New subscribers only. £9.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled.

ADVERTISEMENT. If you sign up to this service we will earn commission. This revenue helps to fund journalism across The Independent.

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 day

New subscribers only. £9.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled.

ADVERTISEMENT. If you sign up to this service we will earn commission. This revenue helps to fund journalism across The Independent.

It's a testament to the strength of the best Ealing comedies that they are so often invoked when new British movies roll along. Nonetheless, it is quite obvious that Michael Balcon's Ealing Studios would never have made films like Made in Dagenham or Attack the Block.

Balcon's Ealing wasn't much interested in women's rights. The studio boss was a patriarch with very chauvinistic opinions. Betty Box, a young female producer in the late 1940s, once told me that Balcon "didn't really approve of women behind the camera". Film historian Geoff Brown has pointed out that "cosy nostalgia and easy assumptions" cloud our view of Balcon, who was a far more complex figure than his image as Ealing's benign headmaster suggests. The classic Ealing comedies were made at a very specific period in British history – the post-war period of the Attlee Government when there was an idealism both about rebuilding British society and reinvigorating the British film industry. As Balcon himself later put it in a famous quote to writer John Ellis: "By and large we were a group of liberal-minded, like-minded people... we were middle-class people brought up with middle-class backgrounds and rather conventional educations...we voted Labour for the first time after the war: that was our mild revolution."

The political dimension was crucial to Ealing – and Balcon's mild revolutionary fervour is something that the studios' successors and imitators can't hope to emulate, even if they try. Under its current boss Barnaby Thompson, Ealing is again making comedies (St Trinian's, Alien Autopsy, Burke and Hare etc.) but these have little in common with Whisky Galore, Passport to Pimlico et al. Another factor in the emergence of the Ealing comedies was the decline in the music-hall tradition. Comedians like Will Hay and George Formby (who had both emerged from the music halls and who both made films at Ealing Studios) were falling out of favour. Producers were casting around for a style of comedy that (as one 1940s critic put it) "grew out of the life of our time, out of the way people face contemporary society and its problems."

There is a tendency today to refer to Ealing comedy as if it was utterly homogenous. In fact, the Ealing films we still watch today weren't at all the carbon copies of one another that some contemporary commentators assume. Nor were they ever quite as cosy as they are remembered. Charles Barr has suggested that in Ealing's universe, we see "the triumph of the innocent, the survival of the unfittest." However, Robert Hamer's Kind Hearts and Coronets, arguably the greatest Ealing film of all, has nothing to do with small-timers fighting back against the big, bad bureaucrats. It's about an elegant but psychopathic killer who murders his way up the family tree. There is an erotic edge to the film too, with Price constantly arranging liaisons with his husky-voiced suburban mistress (Joan Greenwood). As the journalist Simon Heffer has pointed out, Israel Rank, the novel on which it is based, is blighted by its anti-Semitism.

There is invariably something very creepy about the characters played by Alec Guinness in Ealing films, whether the unctuous bank clerk he plays in The Lavender Hill Mob or the "Professor" with the false teeth in The Ladykillers. But perhaps the most sinister aspect about the Ealing comedies is the way they've now come to haunt British film culture. They're exceptional films, justifiably cherished for their craftsmanship, writing and performances – and for their understated, very British humour. Nonetheless, they are still seen as the benchmark against which almost every other British comedy must be judged. That is both debilitating and unfair to contemporary film-makers, who should surely by now be allowed to make their films in peace, without always having to look over their shoulders at movies made in a little studios in post-war west London more than half a century ago.

'The Lavender Hill Mob' is re-released on 22 July. 'Whisky Galore!' is re-released on 29 July. 'Kind Hearts and Coronets' is re-released on 19 August

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks