Donor Unknown (12A), Senna (12A) , 4/5, 3/5

At least the kids are all right

Director Jerry Rothwell's startling documentary Donor Unknown examines a reality only glimpsed at in last year's The Kids Are All Right.

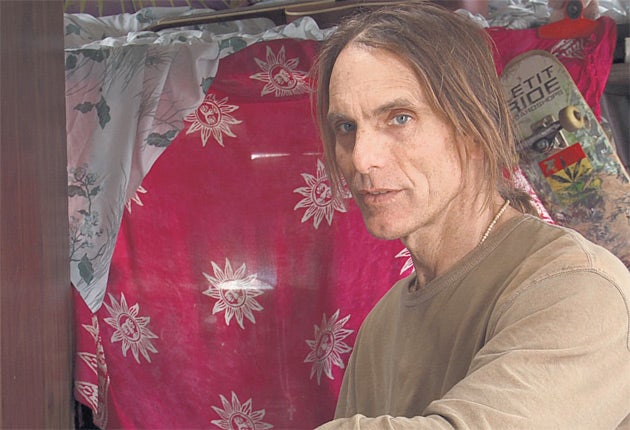

Its subtitle, "Adventures in the Sperm Trade", tips us the wink: what would happen if someone set out to find the biological father she knew only as Donor 150? This was the mission of teenager JoEllen Marsh, who, happily raised in Pennsylvania by two mothers, discovered via an online register that she had a half-sister in New York. More half-siblings gradually emerged, The New York Times picked up the story, and – here's where it gets really interesting – Donor 150 relinquished his anonymity and offered to meet them. His name is Jeffrey Harrison, and he's not what any of his children are expecting – an ageing hippie who lives with four dogs in a broken-down RV parked on Venice Beach, Cal. Back in the 1980s he more or less survived on selling his sperm at $25 a pop, if that's the word.

The film captures, in a manner embracing both tension and comedy, the first meeting between JoEllen, now a 20-year-old, and Jeffrey, whose personality Rothwell has already outlined. "The child is parent to the man" has seldom enjoyed a more pertinent application.

JoEllen, genial, curious and (thank God) open-minded, would be everyone's dream of a long-lost child. Jeffrey is also genial, in his way, but in such a vague, scatty way he barely connects to people. How loveable you find him will depend on your view of a 56-year-old man who treats his dogs as "family" and regards himself as a "fringe monkey", viz the one who warns other monkeys of approaching peril (he's a major conspiracy theorist). In a later scene, he seems more concerned by the disappearance of his broken-winged pet pigeon than in meeting one of his 19-year-old kids for the first time.

Rothwell's camera maintains the right objective distance, seeing the comedy but not pressing it, and inviting us to make our own judgments on the genetic future it lays out. How, for instance, did this man get picked so often from the donor lottery? The mothers who are interviewed seem to agree that Jeffrey's donor profile presented a "happy-go-lucky" guy with a charming benignity towards one and all. And perhaps they were lucky in their choice: they might have picked a depressive, or a psychopath, or a Republican shock jock. Jeffrey might not be your idea of a great dad, but he was at least brave enough to make himself known (his spotting the story in The Times was itself the purest happenstance). The film is a sunnier experience than its troubling subject matter might suggest, mainly on account of JoEllen, sane, amused and genuinely happy about her surprise family of half-siblings. That's the best news: these kids really are all right.

I don't think there's a single sport on TV I would instantly switch off, apart from one. The noise alone – that monotonous dentist's-drill whine of high-speed engines, over and over – is enough to set me on edge. But is Formula One actually a "sport" at all? The question is implicit in the final chapter of Senna, a documentary about the late racing driver. In 1992 Benetton pioneered a car whose technology gave it a clear advantage over the competition. Suddenly it was about who could build the fastest car, not who could drive it.

In the years immediately preceding this development there was little doubt as to who could drive the fastest. The Hackney-born film-maker Asif Kapadia brings a compelling rhythm (his first film was the desert epic The Warrior) to the story of Ayrton Senna, the quietly spoken, fiercely driven Brazilian whose ascendancy began at the Monaco Grand Prix in 1984 and ended 10 years later in tragedy at Imola. Pieced together from a vast array of footage, including YouTube clips and Super8, the film has undeniable dramatic poke, but a noticeable absence of critical detachment. It's enjoyable, for instance, to chart the course of Senna's fractious relationship with his colleague-turned-rival Alain Prost. Both drivers sabotaged one another at crucial stages of their world-title bids, but where Prost looks like a political trimmer and a bit of a sneak, Senna gets barely a ticking-off.

What the film does emphasise is his faith in God and his supreme self-assurance as a competitor. Well-born to doting parents, the skinny teenager, who started out on go-karts, never seems to doubt his destiny, which was just as well given the terrifying speeds at which he eats up the track. "I am as scared as anyone of getting hurt," he says, in which case – why did he drive like a maniac? While the race footage may not enamour you of F1, it will leave you agog at the participants' courage. What's frustrating is that Kapadia, having trawled about 15,000 hours of material, refuses any insight into Senna's personal or romantic life. Audio interviews with F1 journalists fill in some blanks, as do Senna's mum and sister Viviane, though once it emerges that the family gave their "full co-operation" to the film you realise why it's the portrait of a folk-hero rather than a fully rounded human being.

That bias becomes clearer as it approaches the fatal day in May 1994, at the San Marino Grand Prix. Senna had been shocked, like everyone else, by the death of Roland Ratzenberger the previous day, and looks tense and distracted throughout the weekend. This is the point at which references to his "dark side" ought to have been explored. He was caught on film at the corner in Imola a month before he died, saying, "Somebody is going to die at this corner this year", but Kapadia for some reason declines to include it. It strengthens the suspicion that the film was unwilling to plumb its subject's psychology, leaving Senna the man something of a blank and Senna the film rather a copout.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks