Kill Your Friends: Where did it all go wrong for Britpop?

1997: when 3 Colours Red were the next Oasis and no one had heard of digital piracy. Craig McLean was right there, and as the forthcoming film 'Kill Your Friends' revisits the last, deluded golden age of the British record industry, he recalls the excess, the greed, and the hangover

In the Electric Ballroom in Camden, north London, several dozen twentysomethings are partying like it's 1997. That is, they're smoking indoors and bopping about to Elastica.

In the mid-1990s, in the era of Britpop, the rocking and rolling raged on, and on, in an endless loop of gigs and clubs and festivals and fun. Like it would never stop. Like we were never coming down. What could possibly go wrong?

"Guys, remember," shouts a young bloke wearing a walkie-talkie, "it's two in the morning, Saturday night, awesome gig, half-drunk…"

Unlike the film extras, Nicholas Hoult is the only person present who doesn't have to look like he's having a good time. The actor, 25, is standing by the club's bar, exchanging lines of dialogue with Edward Hogg. Hoult is playing the role of record company employee Steven Stelfox. Hogg is DC Woodham, a policeman and wannabe songwriter. Woodham wants Stelfox to listen to his demos. He also wants some answers in the case of the brutal murder of one of Stelfox's colleagues, a fellow A&R man played (hilariously) by James Corden.

The cocaine-gaunt, booze-numb, sex-crazed Stelfox wants to be anywhere but here. Even though this – seeing new bands, banking future hits – is his job. And his job pays very well, in money and in gravy train-riding "benefits". As Hunter S Thompson observed, "The music business is a cruel and shallow money trench, a long plastic hallway where thieves and pimps run free and good men die like dogs. There is also a negative side."

This is the set of Kill Your Friends, April 2014. The film is a rollercoaster yarn of excess, indulgence, fear and loathing in the cash-engorged British music industry of the 1990s. The 28-day shoot of the tightly budgeted £2m film adaptation of John Niven's bestselling 2008 novel is 48 hours from completion. Today, the Electric Ballroom is standing in for a grotty London gig venue (not too much of a stretch), a northern disco and a nightclub in Cannes.

At the latter, misanthropic, music-phobic Stelfox and his record-label colleagues wash down fistfuls of Ecstasy with lashings of champagne to the Chemical Brothers' "Setting Sun". "It's three in the morning and everybody's off their faces!" are the instructions to the extras. "Loads of energy!" On cue, as delirious ravers rave around them, Stelfox and his pie-eyed crew cackle manically. Top of the world, ma.

More than one element of this scenario is familiar to me.

"This film isn't about music," says the actor Joseph Mawle between takes – he's playing a reptilian record company lawyer. "It's about the guys making the deals, making as much money and doing as much partying as possible. And it's despicable and fun, and outrageous and wrong – and sadly it's very, very true."

How true? I can remember the 1990s music scene, despite being in the thick of it. In January 1997, the month that events in Kill Your Friends begin, I joined The Face. My initial job at the style magazine was features editor. This meant helping secure the cover stories. The first month k I was there, the Spice Girls – then at the fizzing height of their Girl Power pomp – were on the cover. A month later, the Chemical Brothers. Another month, the Verve. The biggest acts in the biggest Brit musical explosion since… um, the last one, fighting for the benediction of the coolest magazine on the stands.

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 30-day free trial. Terms apply.

ADVERTISEMENT. If you sign up to this service we will earn commission. This revenue helps to fund journalism across The Independent.

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 30-day free trial. Terms apply.

ADVERTISEMENT. If you sign up to this service we will earn commission. This revenue helps to fund journalism across The Independent.

But just because The Face was cool, it didn't mean we were. We just thought we were. Top of the world, ma.

British youth culture was booming in 1997, an epic year in a hyperbolic decade. It gave us Oasis's "Be Here Now", which sold a titanic 350,000 copies on its first day on sale; it's still the fastest-selling album in British chart history. Radiohead headlined Glastonbury in support of OK Computer, an epochal gig for an epochal album (and I mean that – it's not just the brown acid talking). It was the year of New Labour's victory in the general election, of the death of Princess Diana. Things can only get better. Cool Britannia, wooh.

When I catch up with John Niven, he explains why he set his debut novel in 1997. "It was in some ways the peak of things that had started three, four years earlier," says the Scotsman, who based Kill Your Friends on his own experiences of working at London Records in the 1990s. "It was also the beginning of the end."

You might trace that "start" to April 1994. On the weekend that news came through that Kurt Cobain had killed himself, Niven and I were at the same gig in Glasgow's Tramway. The show was part of Sound City, the kind of music-industry event at which Stelfox and his cronies get wrecked on an industrial scale. The bands: a hot young Scottish band, Baby Chaos, playing with a hot young Manchester band, Oasis.

Grunge was dead, long live Britpop. "That was the start of the golden period," reflects Niven of 1994, the year Oasis released their debut album, Definitely Maybe, "with Liam Gallagher singing: 'You might as well do the white line.'" At the time, Niven's career was taking off, too, as was his partying. And I know of what he speaks, so the narrative structure of Kill Your Friends is painfully familiar.

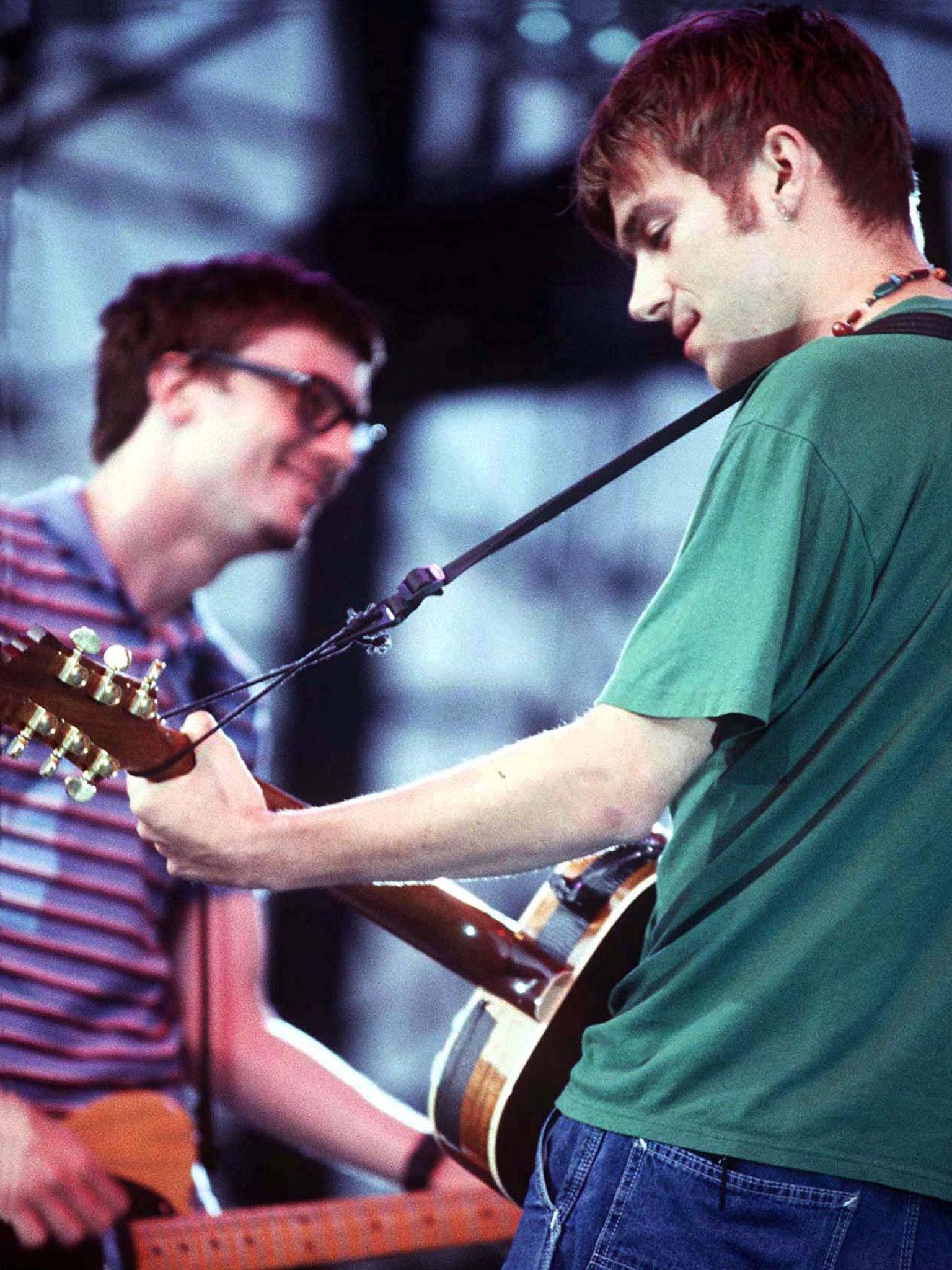

In Kill Your Friends, Niven dedicates a chapter to every month of 1997. He prefaces each with a precis of which band was then selling, which band was signed, which A&R executive made which outrageous proclamation. Here's Creation boss Alan McGee, talking of post-Oasis no-hopers 3 Colours Red: "By the second or third record we'll sell five million. I'm serious."

He no doubt was serious, but only because like so many in that giddy world – like Stelfox – McGee was doing herculean amounts of drugs. Thankfully, The Face resisted covering 3 Colours Red. Or did we?

But that was the tenor of the times: craven hunger and rampaging braggadocio as everyone – labels, journalists, fans – sought the next Spice Girls or the next Pulp. As book and as film, Kill Your Friends does a fantastic job of skewering that headless chicken scramble. Yes, pop kids of 1997, Ultrasound are the future of rock'n'roll. Sadly, The Face did not resist covering them.

There were parties, there were epic benders, and there were jollies galore. As hard as we tried, The Face couldn't get an interview with Radiohead. But we could get invited to Barcelona, where the band launched OK Computer with a gig. I and a photographer were flown to Spain, along with dozens of journalists from around the world, to watch the band perform and, um, not much else. #bestgigever

Or does that hashtag accolade belong to Knebworth? Over two nights in August 1996, Oasis played to some 250,000 fans; two-and-a-half million people had applied for tickets. I was there – albeit, like most of the hundreds of liggers and swiggers crowding the backstage bar, in body if not in mind. The feeling of mass, giddy, lording-it-up, tomorrow-belongs-to-us pomp was everywhere. Which is perhaps one reason why, oddly, a film of the then record-breaking concert has never been released.

As Noel Gallagher said earlier this year, teasing the possibility of a 20th anniversary DVD: "Because we're a bunch of nutters, we've completely forgotten that we had actually filmed the whole thing. With, like, 20 cameras and a lot of what happened on the festival ground as well, like fans arriving, backstage sequences, interviews and flights over the area. Which we've never released. I've no idea why." Maybe because, like a lot of things back then, everything was out of focus?

But as sure as night follows day – as Menswear followed Blur, as Blair begat Brown – the hangover arrived. Once the narcotic napalm cleared, Be Here Now's emperor's clothes were revealed: a very loud, very long, very hollow album recorded by a band so fogged in a cloud of cocaine that in the studio everything was very much turned up to 11 (literally, Noel later acknowledged).

And coming over the horizon as the millennium dawned was a force more destructive still. In 1999, the American record industry, forever tied to ours, enjoyed sales revenue of $14.6bn. By 2009, the figure had more than halved, to $6.3bn. Not uncoincidentally, in 1999, online file-sharing service Napster made its debut. After the madferrit 1990s, recorded music would never sell in the same quantities, for the same amount, again.

In Kill Your Friends, the denouement is, well, savagery on a grand guignol scale. You wouldn't say quite the same about the era's musical full-stop, though Pulp's wearied This Is Hardcore (1998) was troubling. Jarvis Cocker had epitomised the era's swagger when he bum-rushed Michael Jackson's 1996 Brits performance. But behind the scenes, the dream was curdling.

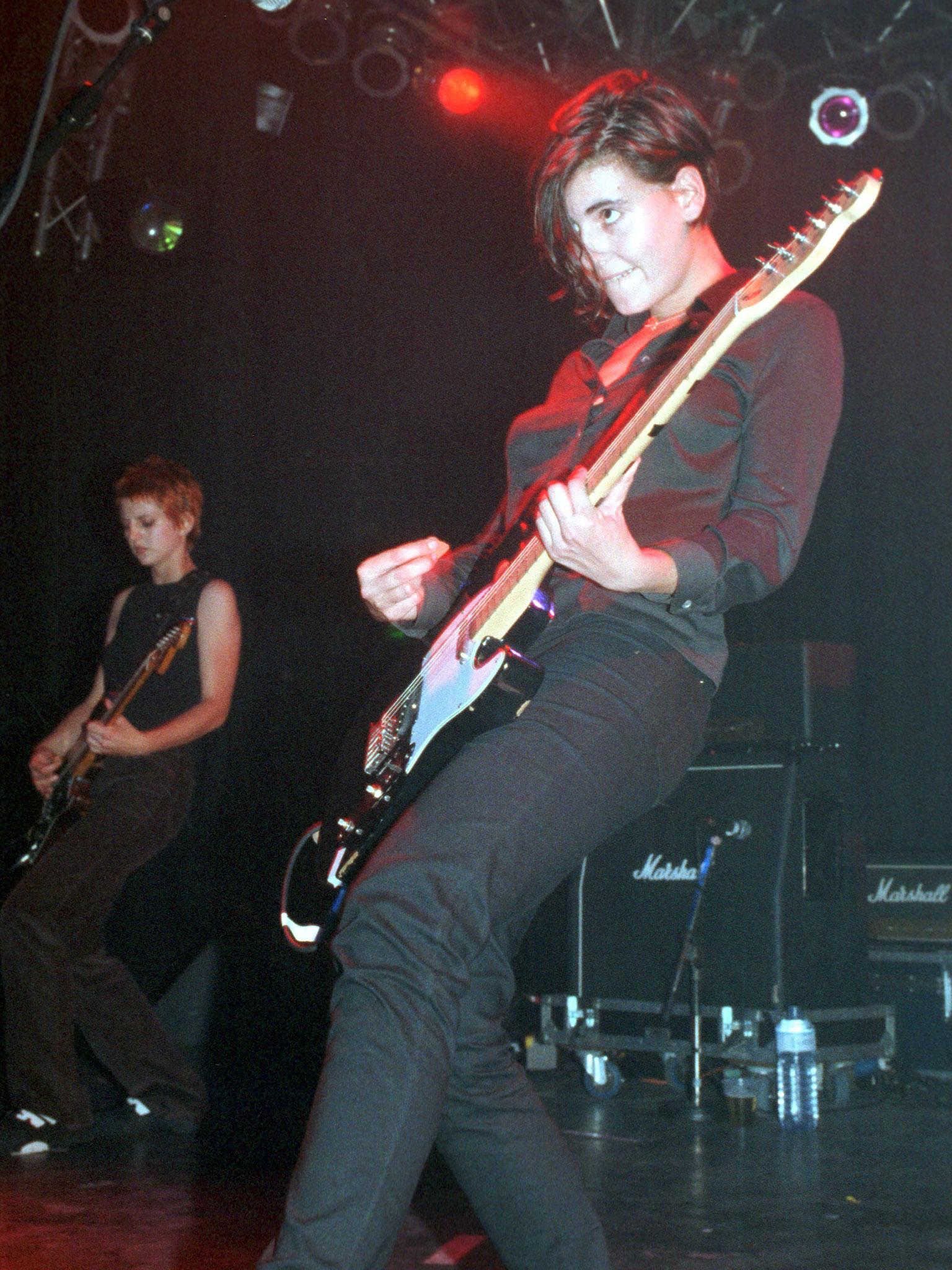

Damon Albarn confirmed last year that Blur's 1997 single "Beetlebum" referenced his use of heroin during Britpop's "golden" years. This was a period in which Elastica, the band led by his equally dazed then-girlfriend Justine Frischmann, embarked on a five-year, £350,000 spending spree in an attempt to make a second album. Cocker, meanwhile, admitted he knew the hedonism had gone too far when he found himself attending a piss-up celebrating Action Man. When the party ended, it ended hard.

I'd go along with that. Having winced and chuckled in recognition at (bits of) the book, and enjoyed something of a Proustian rush on set (ah, the scent of sweet fags in an indie toilet…), I watched Kill Your Friends and experienced a clammy, queasy nostalgia.

"Funnily enough," laughs Niven, "that's exactly what Ed Simons from the Chemical Brothers said his feeling was when he saw it. At first he found it really enjoyable, then he gradually became uneasy and paranoid! So, yeah, that's certainly not a bad reaction."

Those were the days, my friend. Thank God they're over.

'Kill Your Friends' (15) is released in cinemas on 6 November

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks