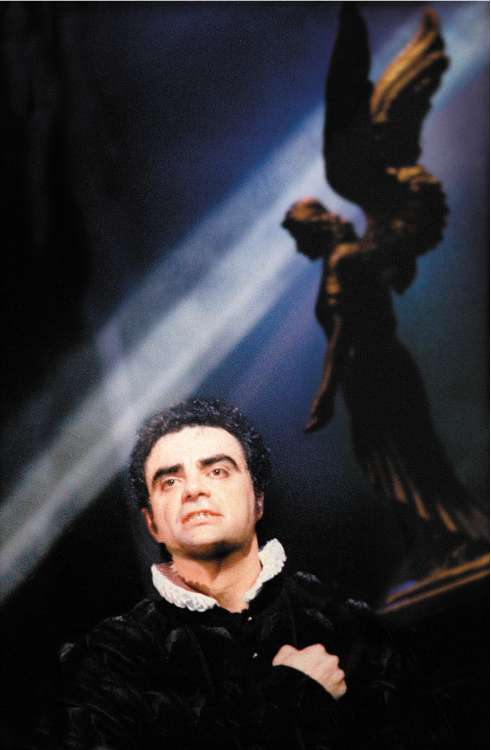

Don Carlo, Royal Opera House, London

Furlanetto commands centre stage as Hytner fulfils all expectations

Nicholas Hytner worked box-office magic for ENO with his endlessly revived productions of Handel's Xerxes and Mozart's Flute. Covent Garden must be praying that he'll do the same for them with his long-awaited Don Carlo. On last night's showing, I think he may.

Supported by designer Bob Crowley's dazzling coups de thêatre, and by Antonio Pappano's band in scintillating form, he directs with such vivid forcefulness – and such psychological acuity – that Verdi's great rumination on theocracy, and on the battle between patriarchy and the brotherhood of man, emerges in its full beauty and menace.

Taking a few liberties with the historical truth, Verdi's opera, based on Schiller's play, focuses on the fatal father-son relationship between King Philip II of Spain and his emotionally deranged son Don Carlo. But Carlo's derangement has a Hamlet-like cause in that Elisabetta, the young woman he loves, is forced to marry his father.

Playing opposite Marina Poplavskaya as Elisabetta – regal in voice and bearing – Rolando Villazon's febrile Don Carlo is the utterly believable protagonist. Spinning out his lines with soaring grace in the cloudlessly happy opening scenes, he seems to shrink and freeze as fate's hammer-blow falls and his Oedipal plight is revealed: he then switches convulsively from crazy elation to pleading, head-banging despair.

But the other side of Carlo is the crusader for freedom, shoulder to shoulder with his blood-brother Rodrigo, the revolutionary Marquis of Posa, sung here with vibrant passion by Simon Keenlyside. Their rousing hymn to liberty reverberates through the evening.

But the drama's centre of gravity is Ferruccio Furlanetto's King Philip, a commanding presence conveying as much by his stillness as by his gloriously resonant voice. Presented here as a bookish prince of darkness surrounded by the coffins of his ancestors, he is one of Verdi's most convincingly complex characters, more than half in love with death, but also locked in a hopeless battle with his deceased father, the Emperor Charles V. As Furlanetto sings it, underscored by its lovely cello solo, the tortured but exquisite soliloquy in which he faces up to his political and sexual impotence becomes the majestic performance we have all been hoping for.

But what gives this work its dialectical power is how Verdi balances and contrasts voices. Rodrigo's baritone becomes the ideological foil to Philip's deep bass, while the death-dealing Grand Inquisitor (the excellent Eric Halfvarson) and the monk who welcomes Carlo into heaven are basses of highly contrasting stripes. Meanwhile Elisabetta's radiant soprano is offset by mezzo Princess Eboli, sung by Sonia Ganassi with all the fury of a woman scorned.

This full five-act version is a long evening, but time flies thanks to transcendent performances by Poplavskaya and Villazon, and to the beauty emanating from the pit.

Meanwhile, Hytner's dark world full of extraordinary visions feels uncomfortably modern, now that religion and politics are once more poisonously intertwined.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments