What's inspiring the Noël Coward renaissance?

After falling out of fashion, Noël Coward's work is reaching a whole new set of admirers. By Ciar Byrne

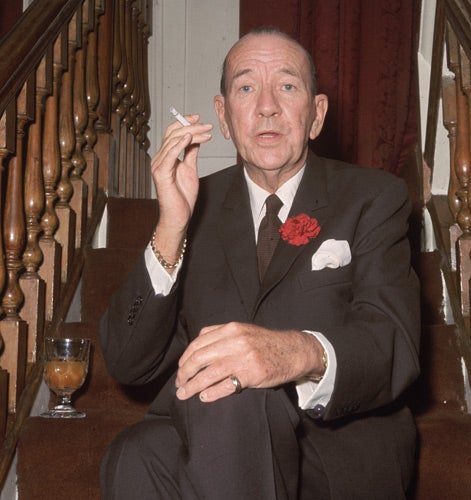

His famous silk, polka-dot dressing gown and elegant cigarette holder both seem to belong to another era. But 2008 is proving to be the year that Britain falls in love with Noël Coward all over again.

The playwright, actor, director, songwriter and all round polymath is enjoying a spectacular renaissance, led by the current National Theatre production of Present Laughter, the play Coward wrote in 1939 about a self-obsessed actor and the circle of women who wish to seduce him - a work often seen as a heterosexualised self-portrait.

Next month, a live stage version of Coward's film Brief Encounter opens at the converted Cineworld cinema on London's Haymarket, and Felicity Kendal is appearing in a new production of The Vortex at the Apollo Theatre under the direction of Sir Peter Hall.

Coward's collected letters were published last autumn. Today, the BBC is bringing out a new box set DVD of his plays, including a 1969 interview on acting, and six radio plays retrieved from BBC archives.

And the Coward revivalism is capped by an unprecedented exhibition opening at the National Theatre tonight, celebrating the diversity of Coward's talent through photographs, letters, costumes, painting, theatre designs and memorabilia, and also revealing his less well-known passion for painting and his tireless support for an orphanage.

The iconic dressing gown is on display in Star Quality: Aspects of Noël Coward alongside a monogrammed handkerchief. The exhibition takes its title from Coward's quip about star quality: "I don't know what it is but I've got it."

To tie in with the current production of Present Laughter, starring Alex Jennings as Garry Essendine, "the world's most famous romantic comedian", a man approaching his 40th birthday and confronting his own mortality with several women in hot pursuit, the exhibition includes a display based on the original performance in 1942 - when Coward played the leading role.

Highlighting Coward's connections with the National, there is also a section dedicated to Hay Fever. The country house farce was the first play by a living playwright to be staged at the National, when it was still based at the Old Vic in 1964, with Laurence Olivier directing. Startling black and white photographs from that production show a young and breathtaking Maggie Smith and her co-stars Robert Stephens, Lynn Redgrave and Edith Evans, as well as a youthful Derek Jacobi.

The sumptuous costume that Evans wore for the part of Judith Bliss is also on display. Although Hay Fever premiered in 1925, it was the later version that sparked a revival in interest in Coward towards the end of his career.

Alongside the photographs, old theatre programmes and costume designs, selected correspondence provides a more intimate portrait of Coward the man. There are letters between Coward and his great friends Olivier and Vivien Leigh. After the couple split, Coward managed the difficult feat of remaining friends with both.

A letter from Leigh expresses her gratitude for Coward's support in the aftermath of the break-up. In a letter to "Larry-boy", Coward advises Olivier not to become Director of the National Theatre, but instead to take Joan Plowright - who he married after divorcing Leigh - and their children and have a complete break in Bora Bora.

Rosy Runciman, the exhibition's curator, said: "I don't quite know how he managed to maintain the close friendship with both of them. It was a lifelong friendship. There were ups and downs, but it was a deep friendship. He was very supportive of Vivien Leigh when she had mental problems."

At one point, when Leigh was in hospital and under heavy sedation, she woke up and the first thing she saw was a bottle of her favourite perfume which Coward had sent her. Olivier - who had not been expecting her to come round so soon - had failed to get a gift on time.

Other letters reveal how Coward's network of friends and acquaintances extended far beyond the theatrical world. There is a letter from TE Lawrence - of Arabia fame - expressing his admiration for Private Lives and a "charming" missive from the then Queen Mother who Coward had given some books by the author E Nesbit.

In Which We Serve, the 1942 war movie that Coward directed and starred in, about the British destroyer HMS Torrin, prompted touching letters from Anthony Eden, Douglas Fairbanks Jr and theatre manager Binkie Beaumont.

Ms Runciman said: "There's a whole range of quite emotional letters showing how much of a chord this movie touched because it was so realistic - Portsmouth lent Coward 300 sailors for the crowd scene."

The exhibition also shows Coward was a keen amateur painter. He started out with watercolours, but was advised by Winston Churchill to move on to oils. Lady In Red, his first oil painting, is on display. The actor visited the Prime Minister at his Chartwell home but there were also tensions between the two. When George VI recommended Coward for a knighthood, Churchill vetoed it. Barry Day, editor of The Letters of Noël Coward, said: "The problem was there were two huge egos. Both wanted centre stage and expected to get it. There may have been a touch of homophobia, but there was definitely professional jealousy."

Another little known side to Coward shown in the exhibition was the charitable work he did for the Actor's Orphanage - a children's home based at Silverlands, a large Georgian mansion in Surrey - of which he was president from 1934 to 1956, taking over from Gerald du Maurier. He once took Marlene Dietrich to meet the orphans and never one to miss a publicity opportunity, she handed out signed photographs of herself.

"He was a very active president and arranged an amazing array of events supporting the orphanage," said Ms Runciman. "In the 1930s, they had these fantastic theatrical garden parties. Coward managed to get together all the great and the good in the acting world to man stalls."

A photograph from one of these fundraising garden parties shows Robert Montgomery, one of the biggest Hollywood stars of the time, standing behind a drum about to beat it. Using his royal connections, Coward would invite friends such as the Duke and Duchess of Kent or Lord and Lady Mountbatten to attend.

After the Second World War, the garden parties were replaced by an event at the London Palladium. A picture from The Night of 1,000 Stars shows Laurence Olivier, Vivien Leigh and John Mills performing.

But why the revival of interest in Coward 35 years after his death? Mr Day insisted: "He's really never been away. For people who are Coward fans, he's always part of our lives. A lot of young people are discovering Coward. He speaks to young people because, underneath the frivolity, his plays are really quite serious and sometimes quite dark.

"Private Lives, for example, is about the impossibility of love. You can see a similar subtext in quite a few of his plays."

In the 1950s when gritty and urban kitchen sink drama became the flavour of the day in the theatre, Coward came to be thought of as "effete and irrelevant". However, Mr Day believes Coward had much in common with the dramatist Harold Pinter, with whom he corresponded: "They both write things that mean one thing on the surface but there's a lot going on behind."

The plays also drip with an irony that is now back in fashion in England - and is even gaining popularity in the US, where irony has long fallen on uncomprehending ears.Alan Brodie, a trustee of the Noël Coward foundation, agreed: "People are realising that he wasn't just a frivolous playwright with champagne and cigarettes. That started when Alan Rickman and Lindsay Duncan did their Private Lives.

"People have also discovered that he was not just a playwright. The songs have come back into vogue, with cover versions and songs such as Mad About The Boy getting a lot of airplay." The opening of the Noël Coward Theatre in 2005 also boosted the writer's reputation, said Mr Brodie.

The angry young men of 1950s theatre may have eclipsed Coward but, in his day, he was every bit as controversial. When it was first staged in 1924, The Vortex - recently revived starring pop singer Will Young - was considered scandalous for its veiled references to drugs and homosexuality. "He came on the scene and blasted the old Edwardian theatre out of the water," said Mr Brodie.

Born on the cusp of a century in December 1899 to Arthur Coward, a clerk and his wife Agnes, the daughter of a Royal Navy sea captain, Coward studied at the Italia Conti School and became a child star. At the age of 14, he was taken up by the 35-year-old painter Philip Streatfield and became part of his circle.

It was Streatfield who introduced him to the bohemian Mrs Astley-Cooper, initiating him into country house living. By 1920, he was a produced playwright with his play I'll Leave It To You performed in Manchester. He went on to become one of the biggest stars of the age, acting and directing plays as well as appearing in films such as Around The World In 80 Days and The Italian Job.

Coward once said: "I'm not particularly interested in being remembered. It would be nice to have a little niche in posterity but it's not one of those dreadful things that haunts me."

But according to Mr Day, Coward worried he would be forgotten after his death - "He knew there was more to what he was doing and people would eventually find it."

"Some day," Coward predicted, "when Jesus has definitely got me for a sunbeam, my works may be adequately assessed." Perhaps that day has finally come.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks