Dunsinane, Hampstead Theatre, London

In a bewildering land fragmented by internecine strife, English soldiers gaze in frustration at girls who cover their hair with long scarves, and keep asking, "Why are we here?" Think you know the time and place? Look at the title.

David Greig's play starts in the final moments of Macbeth, with a sergeant who seems to have been an acting teacher in civilian life handing out branches from Birnam Wood for a forest-simulation exercise. The castle is stormed, and the tyrant beheaded, but the invaders have been misled by faulty intelligence. Not only is Lady Macbeth – Gruach to her friends – alive, she is hiding a son who she is determined will topple the new king. When the Northumbrian general Siward says that, under Malcolm, "Scotland could be at peace", she answers: "The moon could rise at day time and we could call it night. The sun could rise at night time and we could call it day. My son would still be king."

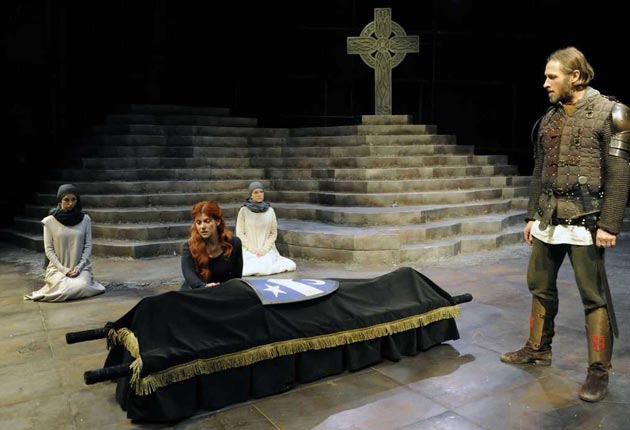

Roxana Silbert's production for the Royal Shakespeare Company is a vigorous one, with mud-stained soldiers storming on to the black stage beneath a Celtic cross, hacking away with broadswords or cheering their victory with filthy songs. Siobhan Redmond's Gruach, looking like a sexier version of Ellen Terry, lashes the English in tones as fiery as the hair cascading down her back, and Jonny Phillips is a highly sympathetic, wearily noble Siward. Yet the flag waving and rhetorical flourishes feel like decorations rather than ebullitions of passion, the winks and nudges about Afghanistan or Iraq like cheap shots (isn't it stay-at-homes, not soldiers, who ask, "Why are we here?"). Gruach seduces Siward, but in a perfunctory way, with no lasting effects. Indeed, with its brisk battles, its dance of stern-faced people stamping, Dunsinane looks a bit too much like a high-quality product of the RSC factory.

Even so, this is an exciting evening, from a writer who can pace his scenes well and is not short on surprises. The play's most emblematic character is Malcolm, a slimily charming Brian Ferguson, whose anachronistic talk of "really unacceptable" behaviour and "more nuanced means" is dropped, when his audience changes, for soft-spoken orders to burn and kill. He reminds you of what a disaffected observer once said of those other Gaels across the water: their tongues are silver, but their hearts are black.

To 6 March (020 7722 9301)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks