The Lion in Winter, Theatre Royal Haymarket, London

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference."Well, what shall we hang – the holly or each other?" Dad (aka Henry II) asks his assembled brood. 'Tis the season to be bitchy in The Lion in Winter, James Goldman's 1966 play, revived now as alternative Yuletide fare by Trevor Nunn at the Theatre Royal, Haymarket. There's nothing like a Christmas reunion for bringing out the worst in families and this Plantagenet clan need no encouragement to put the "feud" in "feudal era". At a festive gathering at Henry's French castle in 1183, the ageing but still virile monarch and his estranged wife Eleanor of Aquitaine, on an exeat from her lengthy imprisonment for leading a rebellion against him, engage in viciously witty spats and elaborate bouts of scheming over which of their sons ("the greedy little trinity") will succeed to the English throne.

Now better known from the 1968 film adaptation, the original play emerges here as an enjoyably bilious entertainment, but mannered to the point of emasculation in its nudging knowingness. Nunn's spirited production does its best to inject life into the relentlessly arch comedy of anachronism, whereby incongruously modern diction ("Hush dear, mother is fighting") and post-Freudian assumptions about love and child-rearing (Tom Bateman's strapping, ferociously resentful Richard the Lionheart is gay because Daddy didn't pay him enough attention) are foisted on these unsuspecting Plantagenets.

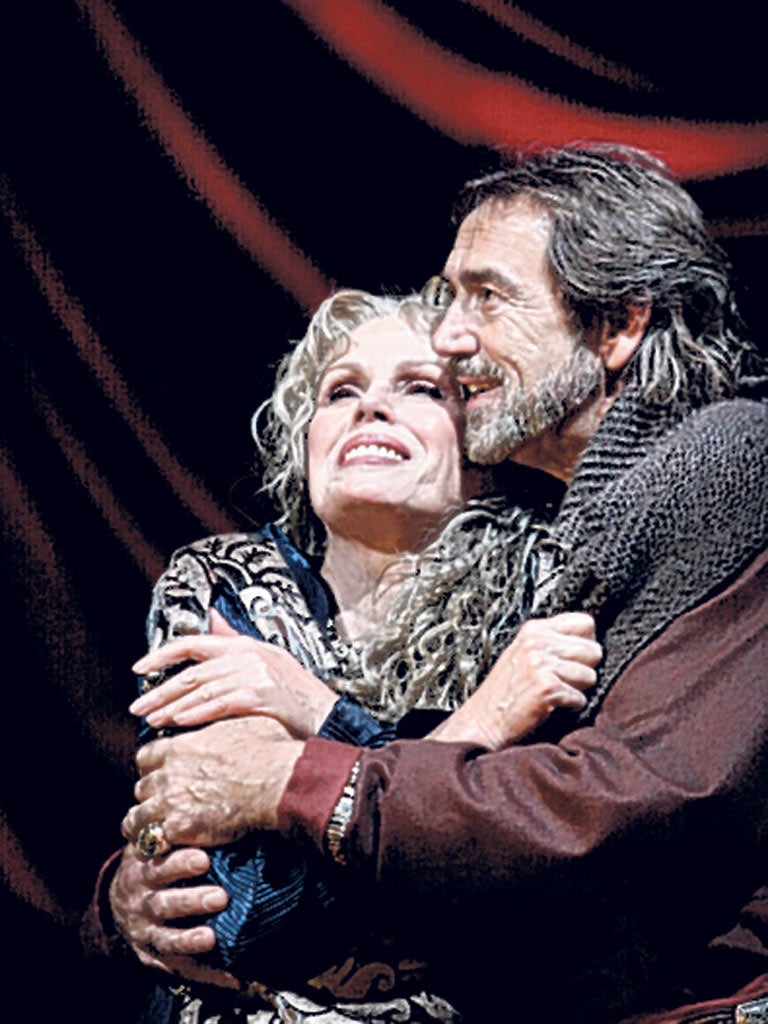

As the plots and counter-plots proliferate and the poisoned barbs whiz by, you may feel you are watching an episode of Dynasty, rewritten by Edward Albee on an off-day, dressed up in medieval mufti, and plonked on a monumental Gothic set. Eleanor has quite a bit in common with Alexis Carrington Colby, another woman who, when spurned by the love of her life, put her heart on ice and turned herself into a diva of deviousness. But Joanna Lumley seems less the Joan Collins of the Middle Ages than a winningly jaunty ex-head girl who delivers her zingers with a jolly-hockey-sticks gusto rather than through a calculating, gritted-teeth smile. Robert Lindsay invests Henry with a raddled sexiness and just the right flourish of self-aware camp. But the couple's pleasure in each other's twisted prowess at cruelty and the sense that the verbal skirmishes are a sort of substitute for sex need to be more powerfully conveyed. As for the play, you learn almost as much about the Stone Age from the Flintstones as you do about the medieval mind from this apolitical and culturally parochial romp.

To 28 January (0845 481 1870)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments